Episode 2: Dissolving rock? (or, how karst evolves).

Post by Andreas Hartmann, Lecturer in Hydrology at the University of Freiburg (Universität Freiburg), in Germany. You can follow Andreas on twitter at @sub_heterogenty.

Didn’t get to read Episode 1? Click this link here to do so!

___________________________________________________________

In the previous episode, I introduced karst by showing how it looks in different regions in the world. This episode will now deal with the processes that create such amazing surface and subsurface landforms. The widely used term “karstification” refers to the chemical weathering of easily soluble rock composed of carbonate rock or gypsum. Most typical is karstification of limestone (consisting of the mineral calcite, CaCO3) or dolostone (consisting of the mineral dolomite, CaMg(CO3)2). If exposed to CO2 rich water these rocks are dissolved to form aqueous calcium (Ca2+) or magnesium (Mg2+) and bicarbonate (HCO3 –) ions. For calcite, karstification is described by the following chemical equilibrium:

![]()

The dissolution of carbonate rock depends on various factors. Imagine a solid block of salt, which you pour water on. If completely solid, the water will flow down the salt surface slowly dissolving the block. If fractured, water will eventually enlarge the fractures in the salt block and dissolution will occur much faster. Now imagine smashing the salt block before pouring water on it. In such circumstances the salt will dissolve even faster as the surface area exposed to the water is much larger.

Karst and its evolution (educational video provided by Eoin Hughes on Youtube).

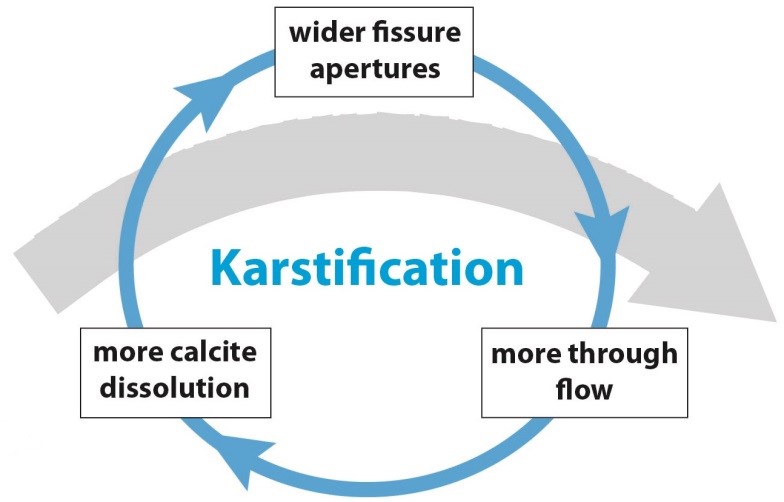

The same is true for karstification. If the carbonate rock is heavily fractured, it will dissolve faster than unfractured carbonate rock. Another factor is the availability of CO2, that depends on the relative amount of CO2 in the air, air temperature and soil microbiotic processes. Other factors are the purity of the carbonate rock, the availability of water, and the supply of CO2 from the surface. As soon as karstification takes place, more water will be able to pass the dissolution enlarged fractures providing more and more CO2, and creating a positive feedback between rock dissolution and water flow:

Positive feedback between carbonate rock dissolution and water flow (Hartmann et al., 2014, modified).

The hydrochemical processes described in this episode of the Of Karst! Series not only create beautiful karst landscapes but they also have a strong and particular impact on water flow paths in the subsurface, which will the topic of episode 4 that can be expected in early 2018. Before, I will present a special feature about karst in the movies as topic of episode 3 in autumn 2017.

Further reading

Hartmann, A., Goldscheider, N., Wagener, T., Lange, J. & Weiler, M. 2014. Karst water resources in a changing world: Review of hydrological modeling approaches. Reviews of Geophysics, 52, 218–242, doi: 10.1002/2013rg000443.

Ford, D.C. & Williams, P.W. 2013. Karst Hydrogeology and Geomorphology. John Wiley & Sons, 576 pages.

___________________________________________________________

Andreas Hartmann is a lecturer in Hydrology at the University of Freiburg. His primary field of interest is karst hydrology and hydrological modelling. Find out more at his personal webpage www.subsurface-heterogeneity.com.