Press release from McGill University of our research published yesterday in Nature Geoscience.

Water scarcity is not a problem just for the developing world. In California, legislators are currently proposing a $7.5 billion emergency water plan to their voters; and U.S. federal officials last year warned residents of Arizona and Nevada that they could face cuts in Colorado River water deliveries in 2016.

Irrigation techniques, industrial and residential habits combined with climate change lie at the root of the problem. But despite what appears to be an insurmountable problem, according to researchers from McGill and Utrecht University it is possible to turn the situation around and significantly reduce water scarcity in just over 35 years.

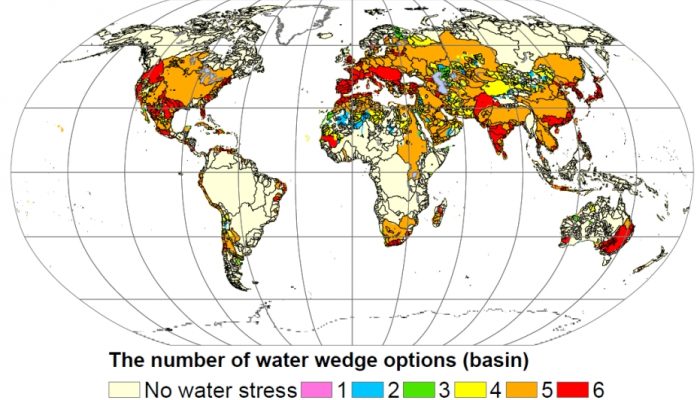

In a new paper published in Nature Geoscience, the researchers outline strategies in six key areas that they believe can be combined in different ways in different parts of the world in order to effectively reduce water stress. (Water stress occurs in an area where more than 40 percent of the available water from rivers is unavailable because it is already being used – a situation that currently affects about a third of the global population, and may affect as many as half the people in the world by the end of the century if the current pattern of water use continues).

The researchers separate six key strategy areas for reducing water stress into “hard path” measures, involving building more reservoirs and increasing desalination efforts of sea water, and “soft path” measures that focus on reducing water demand rather than increasing water supply thanks to community-scale efforts and decision-making, combining efficient technology and environmental protection. The researchers believe that while there are some economic, cultural and social factors that may make certain of the “soft path” measures such as population control difficult, the “soft path” measures offer the more realistic path forward in terms of reducing water stress.

(The details about each of the six key strategy areas are to be found below.)

“There is no single silver bullet to deal with the problem around the world,” says Prof. Tom Gleeson, of McGill’s Department of Civil Engineering and one of the authors of the paper. “But, by looking at the problem on a global scale, we have calculated that if four of these strategies are applied at the same time we could actually stabilize the number of people in the world who are facing water stress rather than continue to allow their numbers to grow, which is what will happen if we continue with business as usual.”

“Significant reductions in water-stressed populations are possible by 2050,” adds co-author Dr. Yoshihide Wada from the Department of Physical Geography at Utrecht University, “but a strong commitment and strategic efforts are required to make this happen.”

Strategies to reduce water stress

“Soft measures”

- Agricultural water productivity could be improved in stressed basins where agriculture is commonly irrigated. Reducing the fraction of water-stressed population by 2% by the year 2050 could be achieved with the help of new cultivars, or higher efficiency of nutrients application. Concerns include the impacts of genetic modification and eutrophication.

- Irrigation efficiency could also be improved in irrigated agricultural basins. A switch from flood irrigation to sprinklers or drips could help achieve this goal, but capital costs are significant and soil salinization could ensue.

- Improvements in domestic and industrial water use could be achieved in water stressed areas through significant domestic or industrial water use reduction, for example, by reducing leakage in the water infrastructure and improving water-recycling facilities.

- Limiting the rate of population growth could help in all water-stressed areas, but a full water-stress relief would require keeping the population in 2050 below 8.5 billion, for example, through help with family planning and tax incentives. However, this could be difficult to achieve, given current trends.

“Hard measures”

- Increasing water storage in reservoirs could, in principle, help in all stressed basins with reservoirs. Such a strategy would require an additional 600 km3 of reservoir capacity, for example, by making existing reservoirs larger, reducing sedimentation or building new ones. This strategy would imply significant capital investment, and could have negative ecological and social impacts.

- Desalination of seawater could be ramped up in coastal water-stressed basins, by increasing either the number or capacity of desalination plants. A 50-fold increase would be required to make an important difference, which would imply significant capital and energy costs, and it would generate waste water that would need to be disposed of safely.

To read the Nature Geoscience article: http://www.nature.com/ngeo/journal/v7/n9/full/ngeo2241.html?WT.ec_id=NGEO-201409

Palash Ranjan Sanyal

Reblogged this on P R S and commented:

A professor I always admired 🙂