David Litchfield completed a second undergraduate degree in Geosciences with the Open University and is currently studying part-time for an MSc in Geophysical Hazards at UCL. He has a broad interest in hazard monitoring methods and how geoscientists communicate their findings with those who need it, and retains a strong connection with the Andean highlands of Ecuador. This summer, David is volunteering at a volcanic observation centre in Ecuador. After his popular first, second and third posts, he writes here about volcanoes in a state of unrest. If you have any comments or questions about David’s work in Ecuador you can email him or find him on twitter: @litchfieldD.

David Litchfield completed a second undergraduate degree in Geosciences with the Open University and is currently studying part-time for an MSc in Geophysical Hazards at UCL. He has a broad interest in hazard monitoring methods and how geoscientists communicate their findings with those who need it, and retains a strong connection with the Andean highlands of Ecuador. This summer, David is volunteering at a volcanic observation centre in Ecuador. After his popular first, second and third posts, he writes here about volcanoes in a state of unrest. If you have any comments or questions about David’s work in Ecuador you can email him or find him on twitter: @litchfieldD.

A lot of my time this summer has been focussed on Tungurahua volcano as reflected in my previous blogs. Of the three Ecuadorian volcanos in eruption at present, it certainly presents a more evident hazard to local populations as Sangay and Reventador are largely isolated. Clearly there’s a need to manage and reduce risk from such a volcano in an eruptive phase but what’s probably more challenging is how we manage one in unrest, where it is not erupting but still shows activity above background levels. Ecuador has its fair share of these too.

Guagua “baby” Pichincha, part of the Pichincha volcanic complex has its vent 11 km from Ecuador’s capital Quito where a population of over 2 million people wraps around its lower eastern flanks. Historical accounts of major eruptions in 1660 indicate that Quito experienced complete darkness for 40 hours as ash and fist-sized pumice reached the capital and caused roofs to cave in. There was some minor activity in the late 19th century but generally it appears to have sat relatively quietly until seismic activity increased from 1997 and lava dome began forming in 1999. A friend of mine who grew up in Quito told me how difficult it was for people to know what to think as the news informed them of this increased risk from a volcano they’d never seen erupt. He described how people moved back and forth between phases of extreme concern when they emptied supermarkets to hoard supplies before then becoming doubtful of the scientists when weeks later nothing had happened. Despite the warning, people were apparently shocked when on 6 October 1999, after what was thought a perfectly ordinary night, they woke to find homes and roads covered in a few centimetres of ash. I then heard how the following day he’d walked outside to find his dad with his mouth wide open, silently staring up at a perfect crystal blue sky interrupted only by the 16.5 km high mushroom cloud rising above the city.

Eruption of Guagua Pichincha, 7 October 1999. Source: Paginario

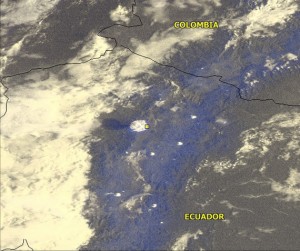

Eruption as seen from space (look at the shadow it casts!), 7 October 1999, Source: NOAA

Dome-building and explosive eruptions continued until 2001. Since that time there have been some phreatic (water influenced) explosions, continued emissions from fumaroles on its remaining lava domes and seismic activity, but life in Quito has gone back to normal. There is even now a cable-car to carry people up to a view point on the slopes and give easier access to a beautiful walk to the peak of Rucu “old man” Pichincha, the older volcano, inactive since about 260,000 years ago and on which Guagua has been growing. But there is still the odd sign of what the city went through during that time if you look closely. The occasional window still has a cross of tape across the pane, encouraged by the authorities over a decade before to minimise flying glass in the case of explosions. This is particularly evident as you head down the street Mariana de Jesus, which is built along the route of a gully from Pichincha and identified as a high risk lahar (volcanic mudflow) route. However, generally Quito is more focussed on another, ever present threat of forest fires in the surrounding countryside. Many of its central parks are marked with ‘Secure Zone’ signs, that I’d first thought related to crime prevention but later discovered were designated places for the population to gather in the event of fires reaching the city.

It’s relatively easy to visit Guagua being a two-hour4x4 drive from Quito so when I took a Sunday trip with friends we didn’t anticipate getting it all to ourselves but all the same we didn’t expect the crowds that greeted us as we approached the refuge. Actually it was somewhat appreciated as we recruited volunteers to help push our car to the side of the track after it stalled and refused to restart in the thin, 4500 m altitude. We’d arrived on the day of a pilgrimage, where people take a 6-hour trek from nearby El Cinto carrying a statue of the ‘Virgin of the Volcano’ and hold a mass at a shrine by the edge of the caldera wall. For a few hours the area was packed with devotees giving yet another example of how culture and religion here is often entwined with its volcanic landscape, this romantic image only spoilt by the empty bottles and wrappers left everywhere from their lunches. Although it was cloudy much of the time, occasionally we were treated with incredible views across the caldera to the younger, active crater where we could clearly see the lava dome and its steamy fumaroles. I also found a plaque recalling the death of a volcanologist here in 2001, the tragedy made even worse when his cousin and a member of the recovery team was injured and subsequently died. This and the two seismic stations I came across serve as a reminder that Quito’s neighbour is unlikely to be finished with them yet.

I would like to express my gratitude to the Instituto Geofísico for this opportunity and to the Open University Ian Gass Bursary for providing financial support. Any opinions, omissions or errors in this blog are entirely my own. Please let me know any comments or questions as I continue my experience over the coming weeks.

Linda Fowler

This makes fascinating reading Dave: looking forward to reading more! Btw ‘guagua’is the local name for a bus in the Canaries! Never knew it meant baby… learn something new all the time (as well as all the hazard stuff!)

Linda

Dave Litchfield

Thanks Linda. Didn’t know about the bus. As far as Ecuador is concerned, Guagua is a word of quichua (quechua outside Ecuador) origin but common use in Ecuador. Pronounced “wah wah” it’s basically onomatapoeic word that sounds like a baby crying.

Pingback: Guest Blog: A Summer of Volcanic Observation in Ecuador (5) | Geology for Global Development