‘Natural disasters’ is a phrase widely used by the geoscience community but how accurate is it? Given the human and societal factors that create a disaster, it has been highlighted that there is no such thing as a natural disaster. Is this simply a convenient phrase that recognises the contribution of natural processes (e.g., earthquakes), are we being sloppy with our language, or are we reinforcing the (incorrect) opinion that disasters are inevitable events, so called ‘acts of God’?

If you hear the phrase ‘natural disaster’ most of you will immediately know what is being referred to. An earthquake devastating a city. A flood destroying huge swathes of farmland, homes and livelihoods. A volcanic eruption (such as that in the image above) covering a community with ash and other volcanic material. A severe storm event (e.g., hurricane) impacting the coastline of a major country.

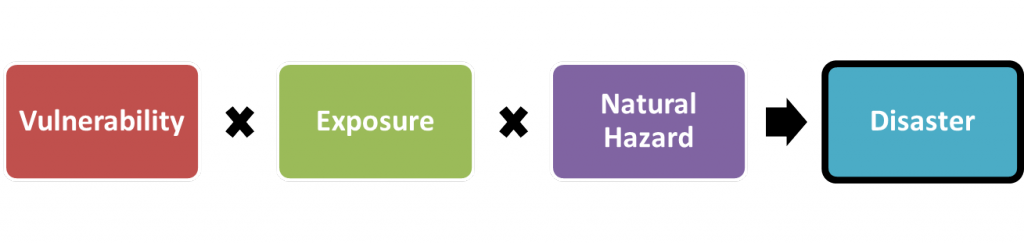

There are four common features to all of the above, three contributing factors and one outcome. There is (i) a natural hazard, a natural process such as an earthquake, flood, volcanic eruption or hurricane. (ii) People, property or livelihoods that have been negatively affected (summed up using the term ‘exposure’). (iii) There are underlying factors that have resulted in those people, property or livelihoods being impacted by the aforementioned natural hazard. Such factors may include education, awareness, having the financial resources and/or health and agility to move. Finally (iv) there is an impact or ‘disaster’ with either people, infrastructure or livelihoods being negatively impacted (e.g., damage, death, physical or mental injury, displacement, loss of livelihood). The relationship between these four components can be expressed in the simple figure below. The precise terms have been defined by the United Nations International Secretariat for Disaster Reduction (UN-ISDR). In reality this equation is not so straightforward, as there are various interactions and aspects of overlap between these components.

Of the three contributing factors outlined above, one of these is normally a natural process (although can be exacerbated by anthropic or human factors) and two are anthropic/human-centred. An earthquake in an area with no population/infrastructure is unlikely to result in a disaster. An earthquake in an area with population/infrastructure that is 100% resilient to earthquakes (i.e., the vulnerability term is ‘zero’) is also unlikely to result in a disaster. The concept of a disaster requires human-centric exposure and vulnerability. It is, therefore, reasonable to say that there is no such thing as a disaster that is ‘natural’. A disaster is the complex interaction of natural processes and individuals or society.

As geologists, with a primary focus on the ‘natural hazard’, we’re maybe not all aware of some of the terminology, definitions or complexities of what’s been outlined above, but most will be aware of the concepts. “Earthquakes don’t kill people, buildings do” is after all a regular quote of the seismology community and one example of the relationship between hazard (earthquake), exposure (number of people in the building) and vulnerability (e.g., the quality of building construction).

Given this understanding, why then do we insist on propagating the term ‘natural disasters’? We’re not alone as the geoscience community, the Guardian Newspaper have a ‘natural disasters and extreme weather’ section on their website. Here are three reasons why we I think we still use the term:

1. Lack of Awareness. It is more common in the geographical sciences than the geological sciences to be taught on all aspects of the disaster equation shown above. Our focus is on earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, landslides etc – and not on issues of underlying vulnerability (rightly or wrongly is another debate). It is therefore very possible that we will go through our university education without ever having any opportunity to consider this and other aspects of disaster risk reduction in much detail.

2. Natural disasters reflects the fact that natural processes are a contributing factor. It could be argued that as the hazard is natural, the use of the term natural disaster works. It separates them from technological disasters (e.g., nuclear meltdown, building collapse) and conflict/war.

3. Terminology doesn’t matter, natural disasters is generally understood by a lay audience and is therefore helpful. A final reason for the term being used is convenience. It is a term that is widely understood to be the negative impacts that occur when a natural hazard occurs. We wouldn’t use it for an event such as a terrorist attack, but we would if a storm hit a city. People know this, and so perceive of the correct thing when this term is used.

These points go some way to describe why the term is used, but what of those (myself included) who object to using it. In other words, let me outline why I think this is more than just semantics and is worth writing about.

a. Working Effectively in a Multidisciplinary Team. Tackling disasters and working to reduce impacts requires a multidisciplinary team, drawing on engineers, geoscientists, social geographers, policy makers, land planners, local communities and many more. Many of those contributing to such projects come from an academic background where they are very familiar with the social nature of disasters. If we are to effectively work together we need to have a mutual appreciation and understanding of key terminology and concepts. Using the term ‘natural disasters’ may (rightly or wrongly) not best represent the depth of the knowledge you have on the nature of disasters. Given the avoidance of the phrase by groups such as the UNISDR, it runs the risk of being misconstrued as a lack of understanding of the complex reasons why disasters occur.

b. (Normally) Natural Processes, Non-Natural Exposure, Non-Natural Vulnerability. The argument that we still include the word ‘natural’ as the hazard process is natural gives an unfair weight to the hazard process, over the exposure and vulnerability. Two of the terms are not natural processes but based on decisions made by individuals and society. The nature of hazards being ‘natural’ also doesn’t take into account possible influence by human activity. A landslide may only be triggered because of road construction, or a flood may be much more severe because of urbanisation. Would those who use the term ‘natural disasters’ still apply this term for these events? The answer is most likely yes, suggesting that the term is used in some part for convenience rather than because of a strongly held opinion that it is important to include the word natural to reflect the nature of the hazard.

c. Reinforcing Unhelpful Beliefs. I think that the strongest argument is that the terminology reinforces a belief that disasters are inevitable. The phrase suggests that the disaster is a natural event, and we have a lot less control over natural events than those linked to human decision making and policy. Given how much can be done by society to better understand hazards, reduce exposure and minimise vulnerability – the emphasise we need to be pushing is one that places pressure on the decision making process to act, and not one that suggests an ‘inevitability’ about what will happen.

So why avoid the term natural disaster? – In order to promote more effective multidisciplinary learning, accurately represent human/societal driven exposure/vulnerability, and ensure that the misconception that these events are inevitable is not propagated.

Do you think it matters? Are you aware of any debate around this within your geoscience community? Please feel free to share your perspectives below!