Today is the start of Earth Science Week, Global Handwashing Day and the UN’s International Day for Rural Women. Tomorrow is World Food Day, and Wednesday is the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty. You could write a blog on any one of these, and the role good geoscience can play! Saturday, as some of you may have noticed, was the International Day for Disaster Reduction, and is the ‘topic’ I’ll be focusing on in this post. This year the key theme was about stepping up for women and girls, a key force for resilience. The UN website stated that… “Women and girls are empowered to fully contribute to sustainable development through disaster risk reduction, particularly in the areas of environmental and natural resource management; governance; and urban and land use planning and social and economic planning – the key drivers of disaster risk”.

As geoscientists our training has a focus on improving the science of natural and environmental hazards, the understanding of the physical mechanisms by which hazards occur and the ways they impact upon the natural environment and physical infrastructure. The appropriate use of good geoscience information is essential for effective disaster risk reduction (DRR). Improved geoscience and understanding of natural processes and their interaction with society is also extremely important. When I was in China I saw a number of incidences where poor engineering and poor understanding of geology was evident. Measures that were meant to increase the resilience of the local population were actually having the opposite effect and exacerbating the problem. Disaster risk reduction must be more than a detailed understanding and appropriate use of geology and engineering.

Many in our discipline would agree, and argue that improving the education of local communities about natural hazards and how to respond to them is also crucial. ‘Education, education, education’ one past prime minister famously stated – and we can sometimes fall into the trap of thinking the same with disaster risk reduction. Education about hazards, and what to do, is another vital part of the jigsaw. However we must be careful to understand and take into account complexities. As Dr Kate Crowley (CAFOD) pointed out in her recent article in the Metro Newspaper – women can have a much greater vulnerability due to their lack of overall education, being unable to read information about what to do during an emergency. Education programmes must take into account issues such as how information is communicated between different family members, how and whether that information is acted upon, and the ways in which communication takes place.

Other factors are vital to reducing vulnerability and building resilience. Community participation in both risk reduction programmes and emergency response plans, and bringing local knowledge and participation into hazard assessments. Also, as I am doing a PhD contributing to the development of a more holistic disaster risk management methodology, I’d argue that the way we compartmentalise different hazards and areas of vulnerability can contribute to the underestimation of risk. There are many places you can read more about the various factors that are required for effective DRR. The UNISDR website is a good starting place.

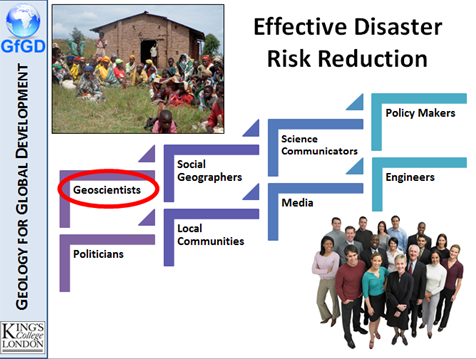

At Geology for Global Development, a key thing we want to emphasise to young geoscientists who want to pursue a career or undertake research that relates to this field is that DRR is a complex jigsaw, with many pieces. Our work is one important piece, but it sits alongside other important factors, disciplines and a variety of practitioners (see the image below, taken from a number of recent talks I’ve given). The development of a range of skills, such as the ability to communicate your research to non-scientists, listen to local communities, and facilitate participatory workshops will significantly strengthen the work you do. We’d also encourage you to read beyond the science in order to better understand the differences in vulnerability both within and between communities. An understanding of differences in vulnerability, for example, between urban and rural populations, or between men and women, can help in focusing the manner and way in which we communicate our knowledge. I’m not suggesting that every geologist needs to become a social scientist, but I am suggesting that for our work to be more effective we need to better understand the context in which it can be used, better understand the reasons for individual and societal vulnerability (not just physical vulnerability, which as scientists we are often more comfortable with) and better communicate with the multiple stakeholders who are involved in DRR.

Last year at the EGU, a session was run on natural hazards and communication between academics, policy makers and practitioners. This year there will be a number of similar sessions including one on the role and responsibility of geoscientists with regards to natural hazards, why natural hazard assessment and mitigation sometimes fail (and how to improve them), and resilience and vulnerability assessments in natural hazards and risk analysis. Abstract submission is open – so if you have something to contribute to these (or the other) sessions – why not consider submitting and joining in what I hope will be helpful and productive conversations.