We should start this post with a declaration of interest. We absolutely love coffee. Whether it’s latte, macchiato, flat white (or cafe au lait for Marion!) we drink it everyday! So for our second installation of “What’s geology got to do with it?’ we’re going to highlight the connections between coffee and geology!

Coop loves his coffee! Source

As well as being absolutely delicious (and often powering an entire community of researchers, PhD Students, lawyers etc through work on a daily basis!) coffee is the 2nd most traded commodity in the world, sitting in a list dominated by other commodities important to geoscience!

- Crude Oil

- Coffee

- Cotton

- Wheat

- Corn

- Sugar

- Silver

- Copper

- Gold

- Natural Gas

Coffee and Soils!

Coffee berries, a variety of Coffeea Arabica. Source – Marcelo Corrêa, Wikimedia Commons.

In order to supply the international demand for coffee, coffee trees require a large supply of nutrients. These nutrients are delivered through soils which are ultimately formed from the breakdown and erosion of rocks. In addition to allowing coffee trees to grow, the soil makeup will also contribute to a coffee’s unique flavour profile. Having said that, the combination of factors affecting taste is so complex, that even from a single plantation you can find variation in quality and taste.

What does coffee need to grow?

Aside from cool-ish temperatures (~20 degrees) and high altitude (1000-2000 metres above sea level), Coffee requires a wide variety of essential elements in order to grow and deliver the delicious stuff we drink. These elements are delivered through the soil profile. The usual suspects like Phosphorus, nitrogen, potassium, calcium, zinc and boron are all very important. The level of potassium influences total sugar and citric acid content while nitrogen is important for amino acid and protein buildup and can influence caffeine build up. Boron is important for cell division, cell walls and involved in several enzyme activities. It also influences flowering and fruit set and affects the yield. In addition to soil type and content, factors such as slope angle (15% is optimal), water supply (good supply with interspersed dry periods are essential) and altitude exert strong influence on the success of coffee growth.

What soils are best?

Coffee can be grown on lots of soils but the ideal types are fertile volcanic red earth or deep sandy loam. For coffee trees to grow it is important that the soil is well draining which makes heavy clay or heavy sandy soils inadequate. Some of the most longstanding and famous coffees are grown on the slopes of volcanoes or in volcanic soil, also known as ‘Andisols’.

Definition of Andisol (USDA soil taxonomy) – ‘Andisols are soils formed in volcanic ash and defined as soils containing high proportions of glass and amorphous colloidal materials, including allophane, imogolite and ferrihydrite.’

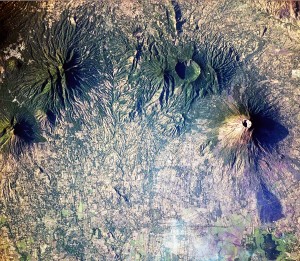

Coffee grows on the slopes of these volcanoes in El Salvador. Source – NASA, Wikimedia Commons

But why are they so fertile? This is due to how young, or immature they are as soils. They still retain many of the elements that were present during the formation of the rock, they haven’t been plundered over hundreds of years of agriculture, they haven’t undergone extensive leaching and are relatively unweathered. This means they often include basic cations such as Mg, Ca or K (which can be easily leached out) and often retain a healthy supply of trace elements. Whilst these soils are very fertile, they only cover around 1% of the ice-free surface area of the earth. They can usually support intensive use for growing coffee and other mass crops such as maize, tea and tobacco. Despite the high fertility of volcanic soils, many do need a nutrient top-up during the growth cycle that comes from natural manure or fertilisers, which are themselves in diminishing supply.

Volcanic soils also have a good structure and texture for coffee growth as they often contain vesicles, which makes them porous and ideal for retaining water. Shallow groundwater is bad for coffee growing as it can rot the roots and it needs to be at least 3 metres deep. Roots of coffee have a high oxygen demand so good drainage is essential.

Where does coffee grow and why?

It is no surpise then that some of the most famous and historic coffee growing regions are in areas of past and current volcanic activity such as Central America, Hawaii and Indonesia. Coffee trees produce their best beans when grown at high altitudes in a tropical climate where there is rich soil. Such conditions are found around the world in locations along the Equatorial zone.

Coffee is grown in more than 50 countries around the world including the following;

- Hawaii – coffee is grown in volcanic soil or directly in the loosened rock. The location and island climate provides good growing conditions.

Volcán de Agua overlooking Antigua in Guatemala an area with a big coffee production industry. Source – Zack Clark, Wikimedia Commons.

- Indonesia – coffee production began with the Dutch colonialists and the highland plateau between the volcanoes of Batukaru and Agung is the main coffee growing area. Ash from these volcanoes has created especially fertile andisols.

- Colombia – thought that Jesuits first brought coffee seeds to South America. One of the biggest producers in the world, regional climate change associated with global warming has caused Colombian coffee production to decline since 2006. Much of the coffee is grown in the cordilleras (mountain ranges).

- Ethiopia – grown in high mountain ranges in cloud forests.

- Central America – rich soils along the volcanic range through central america, equatorial temperatures and mountainous growing areas make this a powerhouse in the coffee growing world.

Coffee and Climate!

Like many crops and food commodities, good coffee requires good climate. For our favorite bean, this typically means temperate regions at altitudes of 1000-2000 m. But climate is changing and this is likely to have a big impact on coffee growth, and by association, on the livelihood of millions of local coffee farmers who rely on its production.

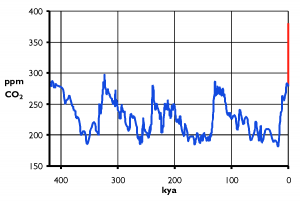

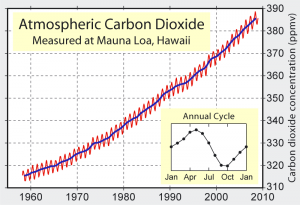

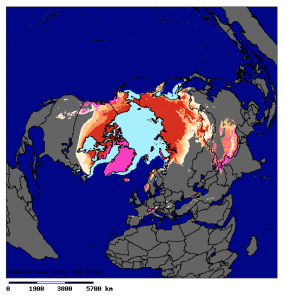

In its latest report out last month, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, the leading body assessing climate change impacts) confirmed for the 5th time what climate scientists worldwide already know: that our climate is warming as a result of human activities. Global temperatures have already risen by almost 1C since the end of the 19th century and will continue to rise at even faster rates over the coming century.

There are two ways in which a changing climate will impact coffee growth and production.

First, increasing temperatures or changes in precipitation will directly affect the areas suitable for coffee growth, leading to a loss in coffee growing environments.

A coffee berry being chewed up by hungry Hypothenemus hampei – Source: L. Shyamal, Wikimedia Commons.

Second, and perhaps most importantly, changing climate and higher temperatures will affect a little insect called Hypothenemus hampei (H. hampei for short). H. hampei is small but lethal. This beetle-like insect is what people call a coffee berry borer. It is the most important threat to coffee plantations worldwide.

Born in central Africa, H. hampei began colonising coffee plantations worldwide with the global movement and commerce of coffee beans. H. hampei likes warm climates. Until about a decade ago, it was very happy munching away at low-altitude beans, below the preferred altitude of our beloved Arabica coffee (between 1200-2000 m in East Africa).

But with rising temperatures, the berry borer can now survive at higher altitudes. On the slopes of Mt Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, H. hampei has climbed 300 m in 10 years.

Mount Kilimanjaro – Source: Muhammad Mahdi Karim, Wikimedia Commons.

H. hampei causes over $500 million loss annually in East Africa alone. The borer is gaining both geographical extent (it is only absent from coffee plantations in China and Nepal, having infiltrated Puerto Rico in 2007 and Hawaii in 2010) and altitude. A further 1C increase will see the borer develop faster and gain new territories.

The Colombia coffee belt – Source: Instituto Geografico Agustin Codazzi, Wikimedia Commons.

In Colombia, where coffee accounts for 17% of the total value of crop production, temperatures in the coffee belt region are projected to rise by 2.2C by 2050. This could both shorten the coffee growing season and allow the pest to make its way above 1500 m.

It has been estimated that Colombian plantations would have to be moved up by 167 m for every degree of warming.

In East Africa, studies predict that Arabica coffee, currently grown at 1400-1600 m, will have to shift to 1600-1800 m by 2050 as a result of rising temperatures.

But it is unlikely that East African coffee plantations will be able to adapt. For one, suitable high altitude habitats are not common. Second, population growth is likely to put a huge demographic pressure on arable land (the population in Ethiopia is set to double by 2050 – see this fact sheet by the Population Reference Bureau) and it is likely that the shrinking available arable land will be used to cultivate other crops over coffee.

The impact of climate change on invasive pest species is something that ecologists are studying worldwide. Small changes in average temperatures can have huge bearings on where these pests live and what they feed on, and this seems to already be the case for the coffee berry borer.

Let’s hope Flo and I can continue enjoying our weekly Four Degrees coffee meetings for many years to come!

Flo and Marion