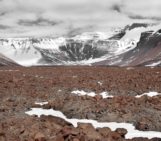

It was October 28, 2022 around 3 p.m. Fascinated by the majestic white snow-covered mountain caps, deep-blue sea ice cracks and light-blue pressure ridges, I gently press my nose against the cold double-glassed window of the Royal New Zealand 757. The tires smoothly touch the ground, and the warm voice of the flight attendant fills the dry air in the aircraft: “Ladies and Gentlemen, welcome to Antarctica.”

Picture 1: Sea ice and snowy mountains in Antarctica. The flight from Christchurch, New Zealand is between 5 to 8 hours depending on the aircraft and weather conditions. (Photo: Julia Martin)

And just like that my life’s dream became a reality! I arrive in Antarctica, the white, snowy, magical continent in the south. The aircraft stops. Time to gear up. Dressed in Scott Base orange attire, we disembark the aircraft. Slowly, we are descending down the stairs in our warm but difficult to walk in moon boots. A gentle breeze and the happy smiles of the ground staff welcome us to Antarctica. Amazed by the stunning white and blue beauty around us, we are guided to our station transport vehicles. For us the Kiwis and our friends the Americans, this is an enormous orange bus (Ivan, the Terra bus) with tires as tall as I am (1.75 m).

Squeezed together like emperor penguins, we are sitting in the huge vehicle. The heating kicks in. I’ve never felt so hot in my entire life! For about half an hour, we are marinating in our own sweat, bumping up and down as we cross the Ross ice shelf until we reach the light-green buildings of New Zealand’s Scott base just in time for dinner (fish and chips!) with the New Zealand prime minister while she was visiting the station.

This was the first day of our expedition.

Picture 2: IVAN, the Terra bus transportes the Americans and Kiwis to Mc Murdo and Scott Base. (Photo: Ruzica Dadic)

We are a team of three women: Ruzica Dadic, Roberta Pirazzini and myself. We are going to camp on the sea ice for four weeks to investigate the physical properties of the snow to understand the role that snow plays on the sea ice engeres balance..

I wake up slowly as the sunshine caresses my cheeks. I open my eyes and begin to smile as I recognize the scenery in front of the window – the mild, calm green of New Zealand’s Scott Base buildings in front of the majestic Mount Erebus. The clear sky is crystal blue, and a soft plume of smoke decorates the volcano’s peak. My smile could not be any bigger, and my sleepiness disappears in an instant.

It’s preparation time. We are delighted as our four drones and our automated radiation stations arrived not only in time but also in perfect condition, all the way from Helsinki. Even the missing pallet from Switzerland was located and sent in time to Scott Base.

With the Scott Base staff’s help, we manage to prepare everything in time and I want to thank the 2022 Antarctica New Zealand Scott Base team for their support and motivation. It was extraordinary, and we are utterly grateful to have been supported by those amazing people.

Next, we head out on the sea ice surveying the area to find a base camp location. In total, we mark five different measurement areas which represent the key features of this year’s sea ice in the McMurdo sound. Usually, the McMurdo sound sea ice starts to form in March and continues growing until around November. In 2022 however, due to heavy storms rushing down from the continent towards the ocean, the sea ice formation was interrupted several times. This resulted in ice with different thicknesses and snow conditions. The “mature ice” (about 2.5 m thick) started developing in March 2022, and the so-called “immature ice” (less than 1.5 m thick) began forming not before August 2022.

Picture 3: Popular yellow-red Scott polar tents anchored to the sea ice via V-threads. (Photo: Julia Martin)

Our main measurement site is close to our camp on the “mature” sea ice. Here, we install our fixed measurement stations as they require daily maintenance. I call it “the garden,” where each station is a flower we must care for.

Basic at Scott Base, besides planning our fieldwork and preparing our science equipment, we undergo countless inductions for the various tasks ahead of us. The most essential induction is the overnight Antarctic Field Training (AFT). We were taught how to set up a polar tent, build a snow cave for shelter, and generally survive the harsh Antarctic conditions. The first night in a polar tent is an adventure I will always remember. Before crawling into my tent after a busy, beautiful day, I sit down on the snow, my face warmed by the dazzling midnight sun. I am overwhelmed with joy as the beauty and magnificence of Antarctica surrounds me. The white delight makes me feel small and unimportant and I sleep like a baby covered in two layers of down sleeping bags, one layer of fleece inlet, and my thermal underwear.

One of my favourite places at Scott Base is the lounge. Huge windows allow the sunlight to enter the room and create a bright and calm atmosphere, making you pause for a second and escape the busy humming of the base life. The national flag is waving outside, rocked from side to side by the stiff Antarctic breeze. I spend some time looking through the binoculars watching a small staff team set up our camp in the vast white open on the sea ice. It is a freezing day. The tents are massive, the four humans tiny. The main tent weighs a ton, and the temperature makes it challenging to install heavy gear. Antarctica does not aim to please. The harsh continent could not care less about what humankind has in mind.

Impatiently I watch the colourful tents grow in the distance, and finally, the day has come when we pack our gear and head out onto the sea ice. Aiming at the yellow squares on the horizon, we slowly approach our home base for the next four weeks. Our little caravan is led by a Hagglund – a dual-cab, all-terrain, amphibious vehicle on four rubber tracks. Hagglunds are widely used for transportation in Antarctica.

We arrive at camp and the air is dry, and the biting cold ambushes my lungs with every breath. We are setting up our four sleeping tents and anchoring them into the sea ice with v-threads. We drill two holes, each at a 45° angle, and pull a string through the hole. This technique is a terrific way to attach equipment safely to any ice surface. The tent guy wires are connected to the v-threads, and chances are exceedingly high that your tent will survive even harsh Antarctic storms. I clearly remember my big smile when I finally got the knot right after several attempts. Our sea ice camp consists of four sleeping tents, a toilet tent, a cold storage tent, a cooking tent, and a fuel trailer.

Setting up the tents and unpacking our cargo takes the rest of the day. The cold slows down every thought and move I make. Exhausted but overly happy, we finally enjoy our home-cooked dinner and delicious evening tea. Later, the happiness vanishes as we slowly start realising our stove is not generating enough heat to keep the tent at the desired temperature between positive 10 to 15 °C (necessary for our lithium batteries’ survival). We assemble our automated weather station inside to monitor the temperature as our cargo with the thermometers still is on its way to Scott Base. It is too cold for the batteries. And so, I share my sleeping bag, not with one but five dreadfully cold and dreadfully large lithium batteries and one drone control unit. My feet are slightly freezing during that first night as my body needs to provide additional heat for the batteries gathering for the sleepover.

I will not lie. The first days out on the sea ice were rough. But then, they almost always are. It is cold, and it takes time to adapt. During the first nights, my breath condensates on the tent wall, and when moving, tiny snow crystals fall on my skin and pierce my exposed cheeks and lips. I tucked very inch of the rest of my body into the insulating layers of my sleeping bag. Undressing, dressing, cooking, personal hygiene and assembling equipment are slow and sometimes painful. The skin on my fingertips cracks, and I must tape it to heal it. You will not feel comfortable in Antarctica if you don’t generate enough body heat. The environment is harsh, brutal, and ice-cold. The continent is not interested in keeping you alive, and you must learn how to keep yourself safe and warm.

Setting up our main measurements field fills my heart with joy as I see our scientific mission grow. Living on the sea ice is incredibly special. It is a unique, extreme, and challenging environment that reduces life to the bare minimum: eat, work, eat, sleep and repeat. And sometimes I put on my headphones and dance with a tear in my eye to warm up before going to sleep. I love every single second. Every ice-cold breath I take, I take with joy. And I realised not only what a privilege it is to be a snow scientist, but that it is what I was dreaming about growing up as a little girl. Dreams come true.

Mafa Lillian Mann

Enjoyed reading this, especially in climate control comfort.

Asmae Ourkiya

Thank you, we’re delighted you found it an enjoyable read!