Folk tales and myths, they’ve lasted for a reason. We tell them over and over because we keep finding truths in them, and we keep finding life in them.

~ Patrick Ness, American-British author (*nae, this Ness isn’t related to Nessie)

Is it an eel? Is it a snake? Is it a diplodocus with fins? No, it’s Nessie!

If there’s one myth that has weathered the passage of time and stands in defiance of all science and reason, it is that of Nessie – the serpent-like monster purported to inhabit a vast freshwater lake in the Scottish Highlands. The creature was named “Nessie” as it has been supposedly spotted and documented in Loch Ness, a lake that stems from the River Ness and extends to the southwest of Inverness in Scotland.

On November 12, 2023, we commemorate 90 years of Nessie ‘evidence’ — a myth, a hoax, a wee bit of Scottish humour, who can say?

When did the ‘Nessie’ myth originate?

The Wikipedia page on the Loch Ness monster lists numerous sightings over the years; the first-ever record may have been in the 7th Century, and the last credible(?) one was in 2021. On November 12, 1933, Hugh Gray took a photograph near Foyers, which was claimed to be the first image of the Loch Ness Monster. The blurred photograph lost credibility soon after. Over the years, more dubious ‘evidence’ piled up: a sketch, another blurred photograph, a 16mm colour film, sonar readings, a doctored negative, the list goes on.

Multiple sightings over the years, regardless of how shaky and unscientific they are, are often held up as proof that Nessie might exist – as Nessie fans live by John Lennon’s adage “I believe in everything until it’s disproved.” Sceptics call it an old, recycled tale from a time when water-beast stories were as common as bagpipes in Scotland. One would think the advancements in photography, and increased boat traffic (and tourism) in Loch Ness would have put paid to the myth, but it seems to have a life of its own.

An extracted, modified version of Hugh Gray’s photograph of the Loch Ness monster, known today to be a hoax. Image credits: Marmaduke Arundel “Duke” Wetherell, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Sometimes, scientific discoveries have been twisted to lend credence to Nessie’s story. In 2019, geneticists from New Zealand’s University of Otago found lots of eel DNA in Loch Ness. While the DNA couldn’t ascertain the size of the eels, the abundance made it impossible to rule out the presence of giant eels – which might explain the sightings over the years, but did little to dispel the myth.

In 2022, palaeontologists found a lot of different fossils of the plesiosaur — a long-necked marine reptile that lived between the late Triassic and late Cretaceous periods. The fossils were discovered within a 100-million-year-old river system that’s now a part of Morocco’s Sahara Desert, and Loch Ness is said to have formed only as recently as 10,000 years ago during the last Ice Age. Yet monster enthusiasts swooped on the “plausibility” of Nessie being a descendant of the plesiosaurs.

Nessie in the public imagination

Ninety years on, the Nessie legend surfaces in unexpected ways in pop culture and public imagination. It has inspired numerous films and books that have kept the myth alive, which have in turn sparked wild searches and funded expeditions — both adventurous and scientific.

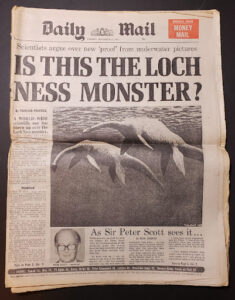

The front page of the London Daily Mail newspaper on November 25, 1975, featuring a painting by Sir Peter Scott. The painting was auctioned by Christie’s in 2012. This newspaper clipping is available on eBay.

Image credits: eBay catalogue.

In 1962, the UK-based Loch Ness Phenomena Investigation Bureau (LNPIB) was formed. Over their 2-year, $20,000-funded mission, they had to get to the bottom of the Loch Ness Monster riddle. During their heydays, they had an annual subscription charge, 1,030 self-funded volunteers who watched the loch from different vantage points with cameras and telescopic lenses. It was disbanded in 1972, their results inconclusive – but what a decade of discovery, dedication and disillusionment that must have been!

For a while now, Google has been adding Easter Eggs — hidden features or messages, inside jokes, and cultural references — into its products. In 2014, Google Maps featured the Loch Ness monster in a tartan hat, and if you asked for directions from Fort Augustus to Urquhart Castle, you also had the option of riding the Loch Ness monster (which is a lot faster than the bus, and the option is still available to travellers today).

On August 28, 2023, hundreds of people took part in a search for Nessie — the biggest-ever hunt for the creature. The hunters arrived with some serious techno-gadgets: sonars to map the lake bed (Nessie’s secret lair, perhaps?), thermal-imaging drones for some surface snooping, and hydrophones to eavesdrop on any underwater reptilian gossip. And just for kicks, they threw a worldwide water-watching party, inviting hundreds of folks to join a live stream – all the better to catch a glimpse of the mythical beast.

The evidence from the hunt was inconclusive, and yet the legend lives on.

The science of myths & monsters

Over the years, there have been many explanations for the Loch Ness monster, mostly hinging on misidentifications – these could be of known creatures, exotic large species or inanimate objects. Interestingly, Nessie isn’t the only humped, snake-like reptile believed to be inhabiting lakes or water bodies. The legend exists in several cultures; mokele-mbembe in the Congo river basin, Leviathan, the sea serpent in the Hebrew Bible, the Lake Van monster in eastern Turkey, Lariosauro in Lake Como, Italy, Gaasyendietha in Lake Ontario, Canada, the Bear Lake monster in Utah-Idaho, USA, etc. Yet Nessie seems to have earned inexplicable fame beyond its geography.

Ever heard of cryptozoology? It’s a pseudoscientific realm dedicated to the investigation of creatures whose existence remains unverified. While distinct from traditional scientific disciplines, cryptozoology has a subculture — with the Loch Ness Monster among its most renowned subjects. Other cryptids — creatures that inhabit the realms between myth and reality, include Big Foot, Yeti, chupacabra, Mothman and the Jersey devil, and each has its own set of staunch believers.

From a psychological perspective, the persistence of the Nessie myth, despite the lack of evidence is what is most fascinating. ‘Why won’t scientific evidence change the minds of Loch Ness monster true believers?’. As per the article in The Conversation, the answers may lie in cognitive dissonance, the allure of plausibility, the psychology of ‘conspiracy theorists’, and the precarious uncertainty of knowledge.

From a geological standpoint, there seemed to be a correlation between Loch Ness monster sightings and bubbles or tremors on the lake’s surface. Luigi Piccardi, an Italian geologist, suggests that monster sightings are the effects of earthquakes caused by the Great Glen fault system – a 100-kilometre (62 mile) long fault that divides the Scottish Highlands. This fault, which mostly moves horizontally with rocks sliding past each other, is the reason Loch Ness exists and is the deepest lake in Britain. It is similar to other famous strike-slip faults like the San Andreas Fault, near San Francisco, USA.

Fiction over facts

Because we live in an age of science, we have a preoccupation with corroborating our myths. ~ Michael Shermer

After countless quests to unravel the Loch Ness monster’s mystery, one truth prevails: it isn’t about finding or proving Nessie’s existence. The quest for mythical creatures was, and always will be a pilgrimage of faith. When global news, hard facts and mountains of data overwhelm us, and we battle our way through propaganda and misinformation, there is barely any space for enchantment and magic. In this world of science and reason, the enduring legend of the Loch Ness monster reminds us of the power of belief and the allure of the unexplained.