The iconic view of volcanic terrain at Bartholomé Island

Introduction

The Galápagos Islands, located around 1000 km off the Ecuadorian coast, are justifiably known as one of the world’s premier wildlife viewing destinations. The isolated terrain hosts some extraordinary animals and plants, many endemic to the islands. It was here that Charles Darwin was inspired to develop his theory of evolution. Without doubt the geology of this region is directly responsible for the morphology of the islands and their fauna and flora. In this article we will explore the stunning geology, examine its influence on the unique wildlife and finish with some tips on visiting the Galápagos.

Geology

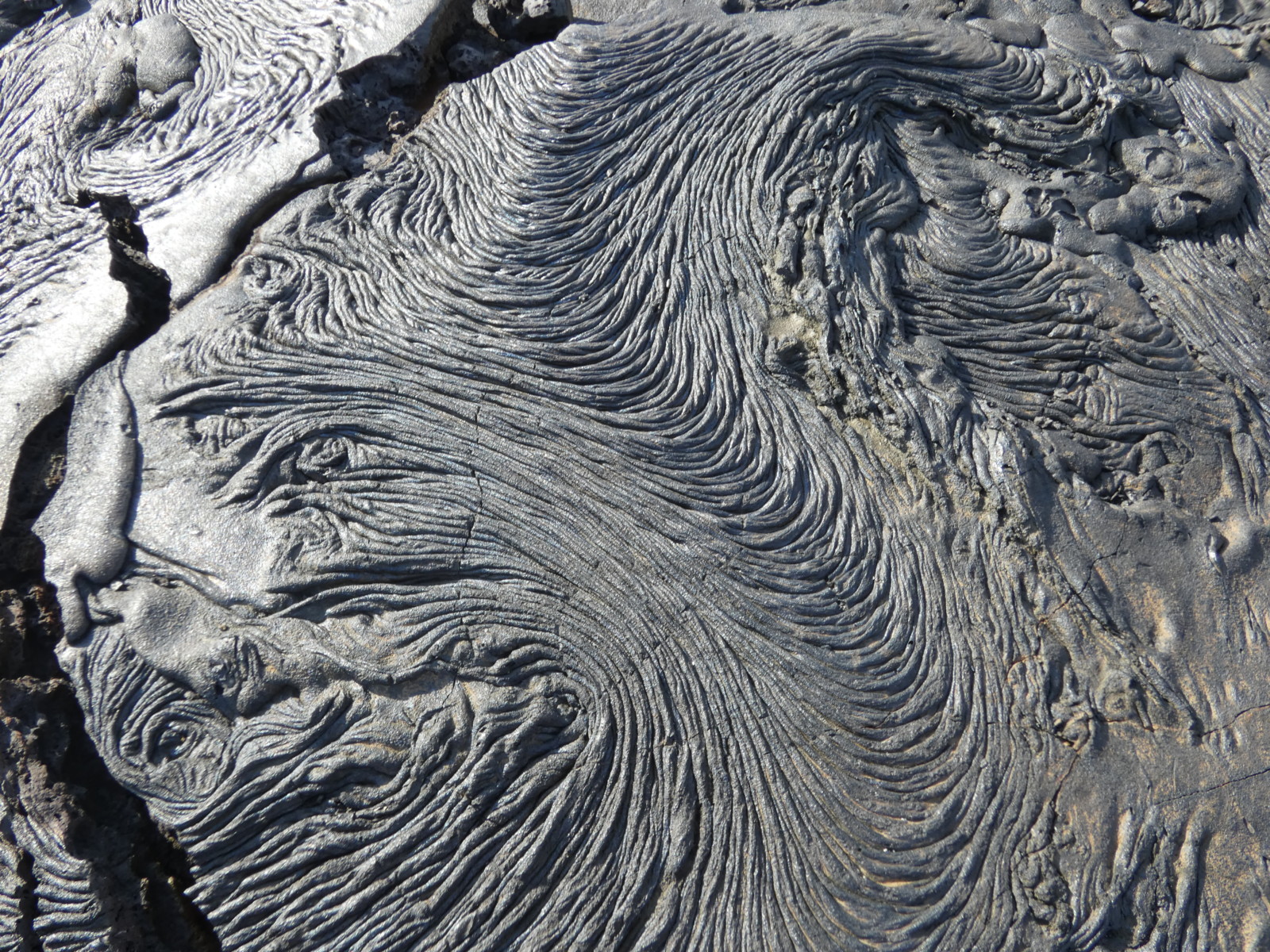

The Galápagos Islands are an archipelago of volcanic islands located on the Nazca Plate. This active tectonic plate is moving eastward as it is subducted under the South American Plate. Much like the Hawaiian islands, an active mantle plume beneath the Nazca Plate has led to repeated volcanic eruptions at the seabed, forming the individual islands. The most recent eruption was at Wolf Volcano on Isabela Island in 2015. The hotspot was initiated at least 70 million years ago.

As mantle plumes near the surface, they begin to melt forming buoyant magma, which occasionally forces its way to surface, producing volcanic eruptions. The situation is complicated in this region, with a mid ocean ridge, the Galápagos spreading centre, located just to the north of the archipelago. Transform faults dissect the mid ocean ridge. The plumes have formed two seamount ridges, the Cocos and Carnegie Ridges, dating back at least 8 million years.

Cross-section through small volcanic cone, Buccaneer’s Cove (left)

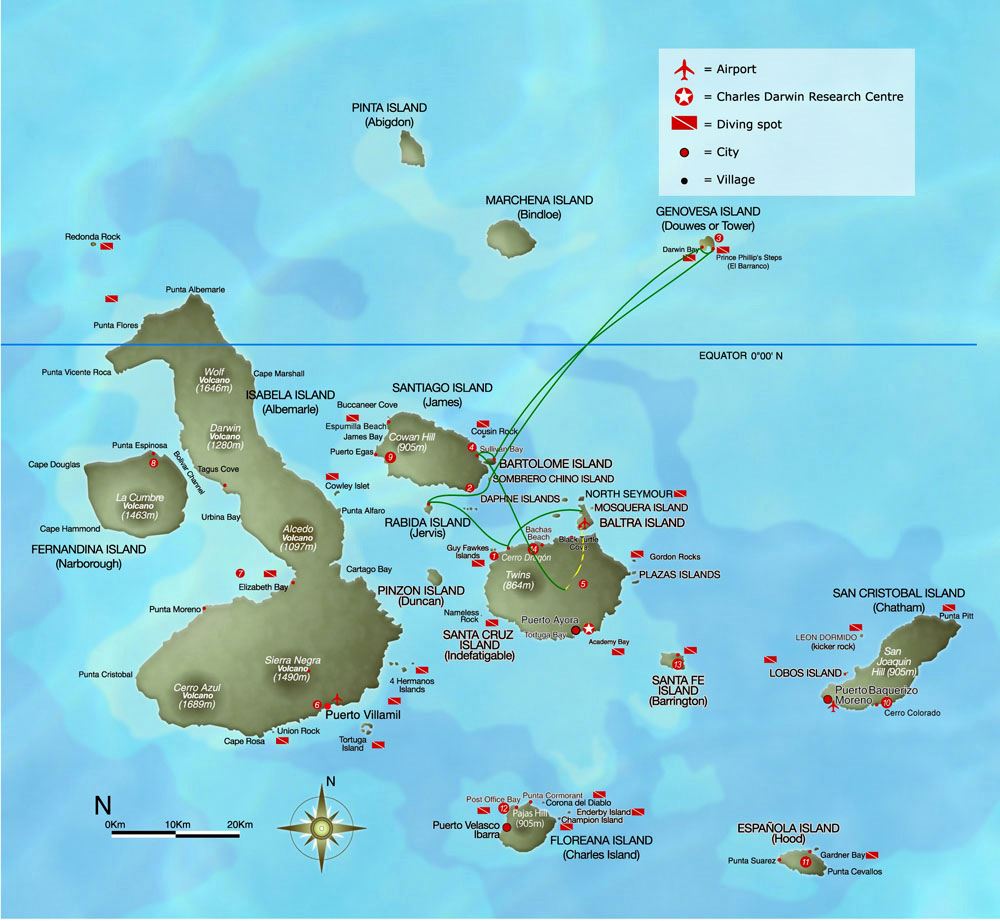

Map showing the tectonic plates in the eastern Pacific Ocean and location of the Galápagos Rift, the spreading ridge that separates the Nazca and Cocos plates. Thermal vents were discovered at the star (https://www.whoi.edu) (right)

Each of the largest Galápagos Islands comprises a single volcano, giving them a distinct rounded shape. The exception is Isabela, which is made up of six volcanoes. The Nazca Plate is moving eastward at around 4 cm/year, so the youngest islands are at the western margin of the archipelago. The oldest islands are Isla Española and South Plaza, which are between 3 million and 4 million years old, while Isabela is around 2 million years old. Many of the western volcanoes are still active, and six volcanoes on three separate islands have erupted in the Galápagos since 1990. Continued lava flows mean that the western islands are growing at a few centimetres every year.

Two distinct types of volcanoes occur in the Galapagos: in the west are large volcanos with “inverted soup bowl” morphologies. To the east are smaller shield volcanoes with gentler slopes. The difference in character is thought to relate to differences in lithospheric thickness, with thicker crust to the west supporting larger volcanoes. The unusual soup bowl shape may relate to the absence of vents on the upper slopes, or to the pattern of magma intrusion.

Dipping volcanic sediments on the flank of a volcano at Vincente Roca Point, Isabela (left) and a beautiful volcanic cone on Santiago Island (soup bowl type) (right)

Cross-section through small volcanic cone (left); The Monk, a weathered volcanic stack (right), both at Buccaneer’s Cove

The volcanic calderas of the Galápagos are unusually large, with their sides repeatedly collapsing over time. They host micro-climates that are more stable than areas at higher elevations and may collect water. Areas where the caldera margins dropped below sea level led to shallow marine conditions ideal for fish of all sizes and marine mammals and reptiles. The western islands have shallower and more gently sloped calderas than those to the east.

Weathered spatter cones on Santiago Island (left) and spatter cones in recent lava field Santiago Island (right)

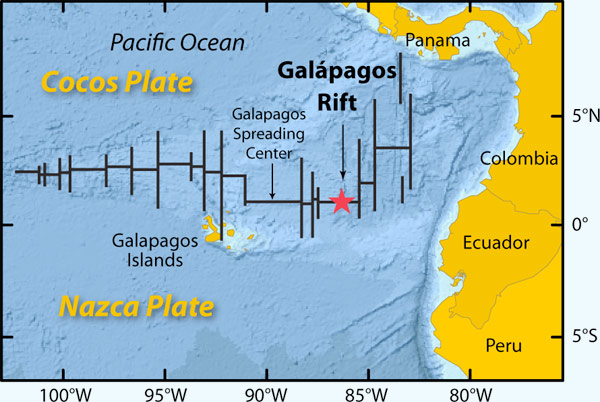

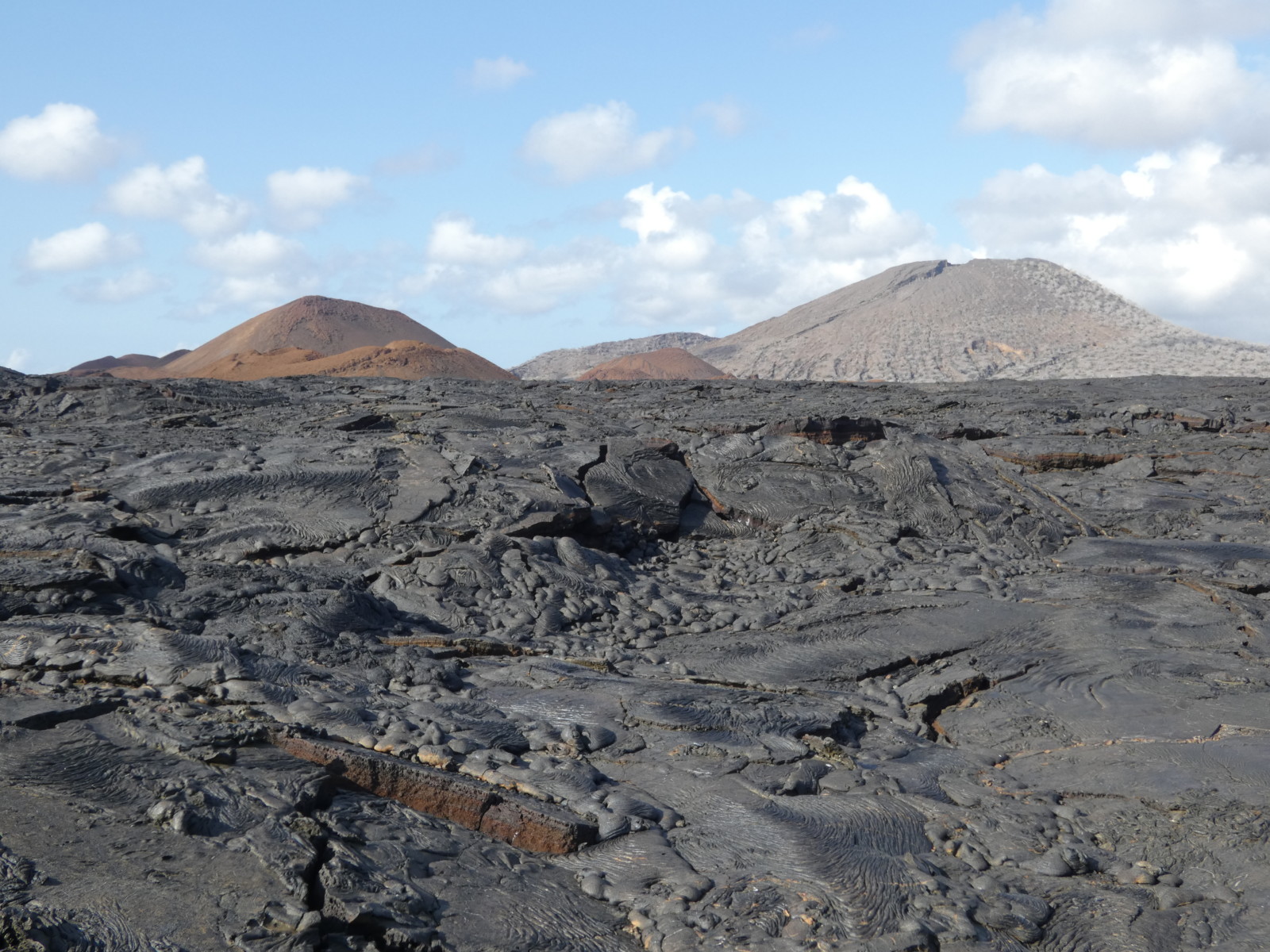

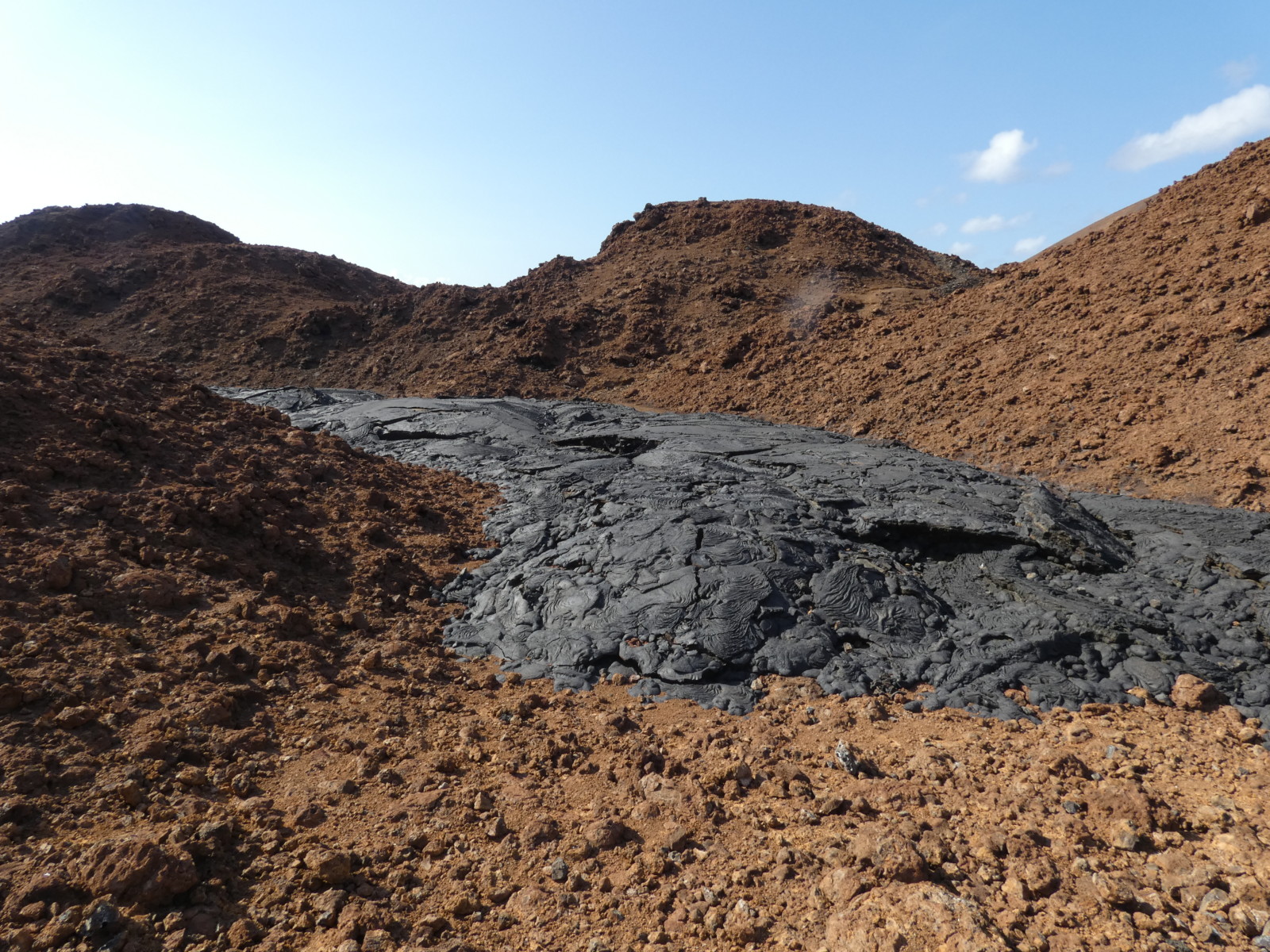

Many other volcanic features can be observed throughout the islands including parasitic cones, both tuff cones, formed by cemented volcanic ash and spatter cones, made up of gobbets of degassed magma that are flung into the air and coalesce upon landing. The Galápagos Islands volcanic rock is largely made up of basalt, comprising jagged a’a lava (more viscous) and pahoehoe lava (which flows more easily), which has a smoother, twisted texture described as “ropy”. You get to walk across recent and older, weathered, lava fields during a visit to the Islands.

Older, weathered a’a lava (left) and younger ropy, pahoehoe lava in a 130 year old lava field (right)

Recent pahoehoe lava flow (left) and rivulets of frozen lava flowing down the face at Vincente Roca Point

There are also lava tunnels formed when the top section of lava cools, forming an insulating crust, and the remaining molten lava continues flowing downslope through the tunnel. When the eruption ends, the drain of molten lava ends as well, leaving a hollow tube that can extend for kilometers. Pit craters form when subterranean magma chambers have emptied, and the roofs collapse to form giant sinkholes. Eruptions usually occur at fissures and not from a central conduit.

Lava tunnel on Santiago Island (left) and Pit Crater at Punta Moreno, on Isabela (right)

Much of the volcanic material is deposited as ash beds. These are often liable to rapid erosion, but may be cemented if sufficiently hot, making them more resistant. The ash beds may host volcanic bombs, which often distort the sedimentary layers as they plumet into the hot ash.

Much of the volcanic material is deposited as ash beds. These are often liable to rapid erosion, but may be cemented if sufficiently hot, making them more resistant. The ash beds may host volcanic bombs, which often distort the sedimentary layers as they plumet into the hot ash.

One of the geological highlights for me was visiting a “raised beach” at Urbina Beach. A whole section of coastline with associated coral reefs was uplifted by 6 m in 1954. It was incredible to walk among large coral heads exposed inland. There were also shells and vertebrate bones littering an area covering several hectares.

Wildlife

How did the original wildlife get here? By flying, floating or swimming. The limited range of animals that made the voyage from the mainland found a relatively virgin and diverse terrane, driving the evolution of new species adapted to each environment. The almost total absence of land mammals, thought to be because they could not survive for weeks without nourishment while floating towards the islands, allowed reptiles to colonize many ecological niches in a way that is not seen in other parts of the world.

It is also likely that most species colonizing the Galápagos had ancestors who were already well suited for its harsh environments. The rarity of onshore predators allowed the slow moving tortoises to evolve into a variety of forms and to increase in size. For the same reason, animals here tend not to fear the unknown, including the many human visitors to the islands.

The older islands to the east are more mature, with thicker soils leading to a more diverse flora, providing thriving environments in which the animals can flourish. It takes time for the lava to break down into fertile soils, but once this has occurred trees can take root, leading to extensive forests that provide excellent habitats for wildlife. Those to the west are more barren, although the challenging terrain and paucity of food has driven evolution at a fast rate.

The islands host 28 reptile species (lizards, chelonians and snakes of which 19 are endemic), 6 onshore mammals (bats and rice rats), 26 marine mammal species (dolphins, sealions and whales), 42 seabirds, 34 shore birds, 21 water birds and 49 land birds, in addition to 13 species of Darwin’s finches. Half the bird species are endemic to the islands. The Galápagos have a low biodiversity due to their isolation from the continent, with animals evolving specific traits to suit a certain niche in the environment rather than diversifying.

Four ecological zones have been defined on the islands: coastal, low or dry, transitional and humid. Mangroves and saltbush dominate the coastal settings; cactus, incense trees, carob and poison apple tress flourish; the transitional zone has taller trees, epiphytes and perennial herbs; and in the humid zone are cogojo, Galapagos guava, cat’s claw, Galapagos coffee, passionflower and some types of moss, ferns and fungus.

Four ecological zones have been defined on the islands: coastal, low or dry, transitional and humid. Mangroves and saltbush dominate the coastal settings; cactus, incense trees, carob and poison apple tress flourish; the transitional zone has taller trees, epiphytes and perennial herbs; and in the humid zone are cogojo, Galapagos guava, cat’s claw, Galapagos coffee, passionflower and some types of moss, ferns and fungus.

Mangroves at Elizabeth Bay, growing on the lava fields (left) and Incense trees and succulents seen at Seymour Norte island, growing in poor quality thin soils (right)

Amazing animals

Below I have selected some diverse animals from the Galápagos that demonstrate adaptations driven in part by the geology. This was a tough choice, and we are merely scratching the surface, as almost every animal has special traits to help it survive in these harsh conditions. We will start with the reptiles:

Galápagos tortoises – there are fifteen species of giant tortoise of which eleven are still living to this day. The different species are adapted to graze on different plants, with the saddleback tortoises having evolved to feed upon tall bushes and cacti. The most famous tortoise is Lonesome George, who was the last surviving member of the Pinta Island tortoise species. He lived to over 100 years in age, with several unsuccessful attempts to breed him over the years. New evidence suggests that hybrid Pinta tortoises may still be living elsewhere in the Galápagos. The tortoises can reach almost 2 m in length, weigh close to 400 kilos and may live for up to 175 years. For anyone wondering whether a tortoise could float so far, in 2004 an Asian Tortoise was found on the coast of Tanzania, some 750 km from its origin.

Galápagos tortoises – there are fifteen species of giant tortoise of which eleven are still living to this day. The different species are adapted to graze on different plants, with the saddleback tortoises having evolved to feed upon tall bushes and cacti. The most famous tortoise is Lonesome George, who was the last surviving member of the Pinta Island tortoise species. He lived to over 100 years in age, with several unsuccessful attempts to breed him over the years. New evidence suggests that hybrid Pinta tortoises may still be living elsewhere in the Galápagos. The tortoises can reach almost 2 m in length, weigh close to 400 kilos and may live for up to 175 years. For anyone wondering whether a tortoise could float so far, in 2004 an Asian Tortoise was found on the coast of Tanzania, some 750 km from its origin.

Wild giant tortoises on Santiago Island

Iguanas – two types of iguanas inhabit the islands, marine and land iguanas, thought to have evolved from a common ancestor that floated to the islands from the mainland. The marine iguana is the world’s only seagoing lizard and is an excellent swimmer, diving to feed on algae coating rocks on the seabed. It has evolved a flattened nose to assist with this feeding technique. There are striking colour variations between the seven subspecies, ranging from black to green to pink on different islands. These animals can spend up to an hour underwater on a single breath.

Iguanas – two types of iguanas inhabit the islands, marine and land iguanas, thought to have evolved from a common ancestor that floated to the islands from the mainland. The marine iguana is the world’s only seagoing lizard and is an excellent swimmer, diving to feed on algae coating rocks on the seabed. It has evolved a flattened nose to assist with this feeding technique. There are striking colour variations between the seven subspecies, ranging from black to green to pink on different islands. These animals can spend up to an hour underwater on a single breath.

The algae is fostered by icy, nutrient rich currents upwelling off the west coast of the Galápagos, which also sustains penguins, sea lions, fur seals and cetaceans that would otherwise struggle to feed year round in equatorial waters. The reason behind the cold upwelling currents is that the deep ocean, fast flowing Equatorial Undercurrent (EUC) collides with the islands lying in its path and is held in place by Coriolis forces related to the Earth’s spin.

Land iguanas tend to nest in burrows, partly as a defence against introduced dogs. Like their marine cousins, they are ectothermic (cold blooded) they need to warm up before embarking on feeding or other activities. The males are highly, territorial, defending their territories against intruders by engaging in head-butting battles. They can breed with the marine iguanas giving birth to barren hybrids.

Land iguanas tend to nest in burrows, partly as a defence against introduced dogs. Like their marine cousins, they are ectothermic (cold blooded) they need to warm up before embarking on feeding or other activities. The males are highly, territorial, defending their territories against intruders by engaging in head-butting battles. They can breed with the marine iguanas giving birth to barren hybrids.

Turtles – the local subspecies of green turtle abounds across the islands. At one point I could see seven turtles swimming through the shallow coastal waters while snorkelling. The turtles rely on the rich, coastal algae growing on the rocky seabed, which thrives due to the cold upwelling currents. Nesting sites are a common sight at the top end of the generally sandy beaches.

Green turtle swimming in the shallows (photo: Katya Kopaskie). It is common to be washed against them while snorkelling

There are a variety of marine mammals, ranging from sea lions to fur seals, from dolphins to whales. We were lucky enough to see a whale (possibly a Bryde’s Whale) at sunset as well as several schools of dolphins. However, the most common marine mammals are the sea lions. They too thrive in the cold, nutrient rich waters. The sea lions are very playful and spend a lot of time frolicking in the shallows. They are surprisingly good climbers and often ascend to the cliff tops, presumably to get a better view of the coast, or a sunny spot to snooze. Fur seals are also fairly common, but their thick fur means that they need to stay out of the direct sunlight to avoid overheating.

There are a variety of marine mammals, ranging from sea lions to fur seals, from dolphins to whales. We were lucky enough to see a whale (possibly a Bryde’s Whale) at sunset as well as several schools of dolphins. However, the most common marine mammals are the sea lions. They too thrive in the cold, nutrient rich waters. The sea lions are very playful and spend a lot of time frolicking in the shallows. They are surprisingly good climbers and often ascend to the cliff tops, presumably to get a better view of the coast, or a sunny spot to snooze. Fur seals are also fairly common, but their thick fur means that they need to stay out of the direct sunlight to avoid overheating.

This sea lion, seen at Tagus Bay, decided that a kayak was a great place to hang out

Marine invertebrates – the most commonly seen are the Sally Lightfoot Crabs, exhibiting striking colours. They are rumoured to have been named after a Caribbean dancer, due to their extreme agility. Female Sally Lightfoot crabs carry their eggs around with them on their stomachs until they hatch into the water. They feed on organic debris. Ghost crabs are also seen scraping the sand for food. Both species rely on nutrient rich waters to supply their food source.

One of the ubiquitous Sally Lightfoot crabs

Birdlife – most memorable of the all the fauna are the birds. Walking through nesting colonies in places like Seymour Norte Island is like being on the set of a wildlife documentary. Three types of boobies live on the islands, Blue footed, Red footed and Nazca boobies. They are named after the Spanish word for clowns – bobo. The blue and red footed boobies use their brightly coloured feet for display during courtship, lifting them up to show their prospective mates. The bright colours signify good health and a robust diet. Boobies have a special air chamber in their skulls allowing them to dive into the water at high speed, to catch sardines. They nest in the incense trees and are adapted to life in arid coastal settings typical of the islands.

Frigate birds are large, dark seabirds with very long, pointed wings. Their bills are long and hooked. They soar over the sea and harass other birds to steal their catches, hence their nickname of the pirates of the sea. They like to follow the small cruise vessels for hours, barely needing to flap their wings. They are incapable of landing on water as they lack the oils to keep their feathers dry. Males have a striking red gular pouch that is inflated during display. The frigate birds rely on other birds for food, birds that in turn rely on the nutrient rich waters.

Male inflating his pouch for display on Seymour Norte Island.

There is one flamingo species that is resident to the Galápagos Islands, the Greater Flamingo. Some experts consider the Galápagos residents as a separate subspecies. They are unmistakable, with bright pink colouration (not due to eating prawns) and kinked bills. They usually feed in small groups in saltwater lagoons developed in the pit craters formed by localized magma chamber collapses.

Flamingos in lagoon at Punta Moreno, Isabela

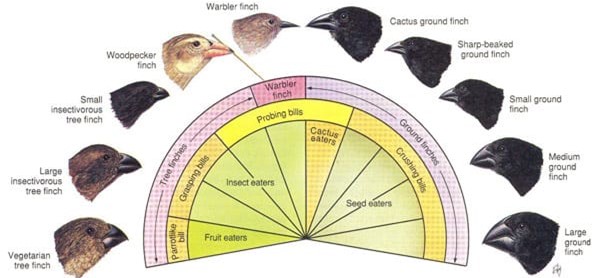

Darwin’s Finches (image from www.galapagosislands.com)

Darwin’s Finches or Galápagos Finches – small land birds with generally dull colouration, short tails and wings. Their bills vary greatly in size and shape from island to island, leading Darwin to muse upon the possible reasons why this should be. The 13 different species of finches all stem from a common ancestor, but have evolved to take advantage of different diets including cactus, seeds, parasites and even blood.

Our final bird is the Galápagos Penguin. It is thought that storms and ocean currents washed the first penguins from Southern Chile to the islands. They are the only species of penguins which can be found in the northern hemisphere. To survive in the warm climate, they have evolved to have far less body fat and feathers than their cold-weather counterparts. They also have bare patches of skin around their eyes and by the base of their bills. This helps them lose body heat and stay cool throughout the summer. Due to the limited food supply, they are one of the smallest penguin species.

Summary

The flora and fauna of the Galápagos Islands are low diversity but have evolved to adapt to challenging living conditions, forced on them by the isolated, volcanic, geological setting. As a result, almost half the species of vertebrates are endemic. They have colonized volcanic environments and taken advantage of abundant food in shallow marine conditions. They are typically very tame as there are few predators onshore meaning that you can get up close in a way that is not possible in places like Africa. A visit to the Galápagos is one that you will remember for a lifetime – a unique experience where the reality really does match what you see on nature shows on TV.

Getting there

There are around 70 visitor sites scattered through the Galápagos islands which are usually accessed by following one of three separate cruise itineraries: central and northern, western or southern. Boats usually sleep 16 passengers with around 8 crew, although there are a few bigger boats. The classier the boat, the better the food and the more educated the guide, the more expensive the cruise. Typically, you can expect to pay anywhere from $400 per person per day and upward, with the cost of international flights on top (the internal flights from Quito to the Islands are usually included in this price). There is also the option to be land based on an island and then to do day trips to the hot spots by zodiac or taxi boat.

Our boat, the MV Bonita, at anchor

I would recommend doing a single 5 day Galapagos itinerary and then 4 or 5 days in the Amazon. The daily program usually involves a morning hike, snorkelling before and again after lunch, and another hike later in the day. I think that only two groups are allowed to visit each site at a time. Before you go, I would also consider whether sea sickness might ruin your holiday. We were lucky and had calm weather (several people still felt rough at times), but later in the season it is supposed to be stormier.

All photos taken by the author unless stated.

References available upon request.