The Academic Identity Crisis

Ever googled yourself to check if your h-index went up? Compared your publication statistics to a peer? Published in a paywall journal while cursing the system? – Same.

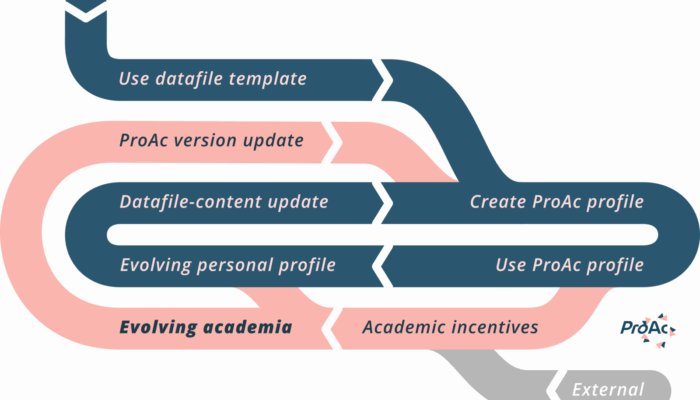

Welcome to the slightly neurotic world of academic evaluation—where current incentives often pull us away from the values we hold as scientists: curiosity, creativity, responsibility, and even actual scientific purpose.

Overall, academia rewards intermediate-impact paper productivity—not mentorship, outreach, or open science. It is a misalignment that fuels burnout, misguided practices, and overlooked contributions. We are pushed to publish in high-impact journals not for cross-disciplinary audience reach, but for career points. We often create new PhD positions not just for long-term knowledge advancement or train the next generation, but to publish more and meet our own funding metrics. We cite friends and ourselves not always for scientific completeness, but because it helps the game; our own game. And the goal is simple: a job a series of many short jobs and also funding, awards, prestige, etc.

Figure 1: Academia’s misdirected incentives. Feel free to add more (and your reactions!) in the comments down below.

The ranking we do not deserve

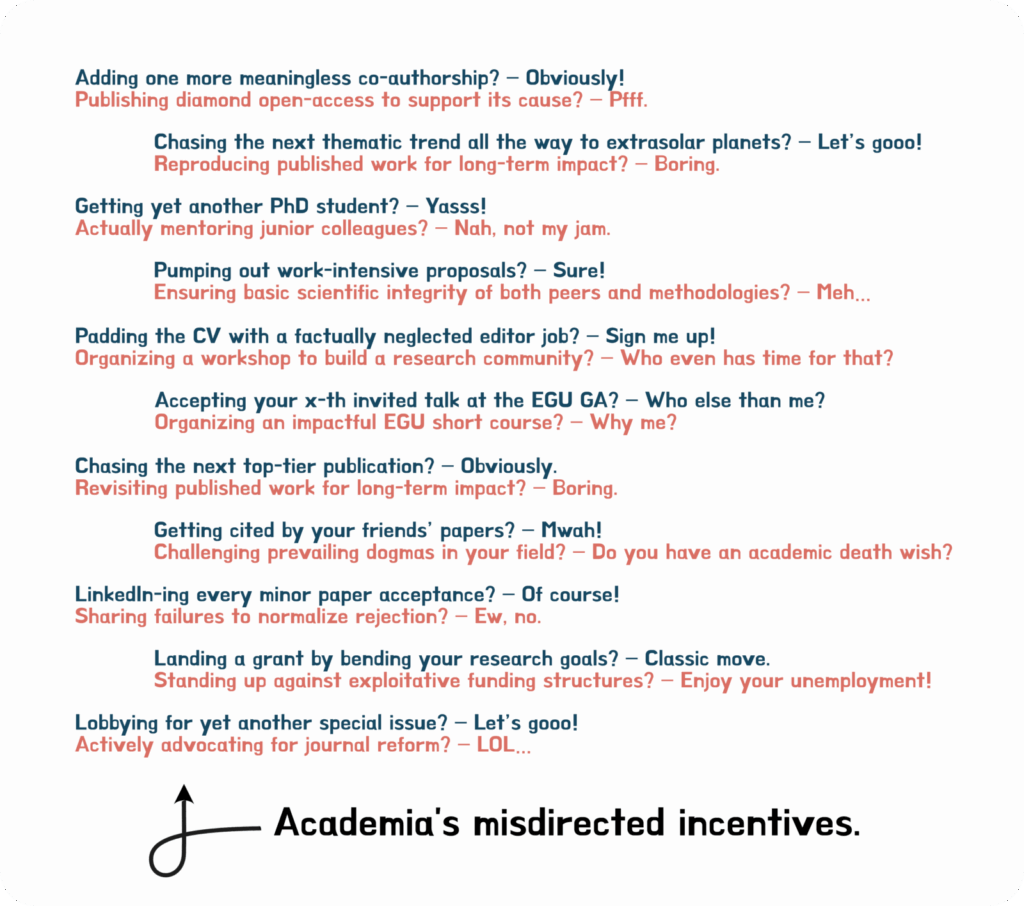

Academic evaluation drives grants, jobs, and prestige. To evaluate academics, we decided to rank people against each other. And for what now seems a too long time, we ranked academics based on one number only.

Yes, here we go, the h-index (Hirsch, 2005): One single number to rank us all against each other based on the amount of visible peer-reviewed papers we have managed to publish. It has been widely used because it is convenient, time-effective, and objective.

However, in most cases evaluating academics, the total number of visible peer-reviewed publications is not what should be focussed on (or certainly not only). And even if it is, this one single number is misused, gamed, and biased to a degree that it is now even disowned by its own inventor (see Crameri, 2023 https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4899015, for in-depth details and references).

There are countless well-meaning reform efforts to rank academics. Alternative metrics are also only directed at the researchers’ output and often raise new problems (see Crameri 2023, for a long list). Institutions can publicly pledge support for a reform on assessment by signing up for efforts such as the declaration DORA (https://sfdora.org/) or the coalition CoARA (https://coara.eu/). Both advocate for a richer, more complete assessment of research and researchers, but a specific working implementation still seems to lack, as written CVs, for example, are time intensive and favour eloquent and persuasive academics over others.

So, as of today, the h-index still lingers. If you have been around long enough, you will find it haunting rejection letters, lurking on your Google Scholar page, echoing in award justifications and presentations. Even when explicitly deemed unfit by an entity, the flawed metric seeps in quietly past the signed DORA badge—through external reviewers, panels, and nominators. It still ranks all of us—including our skills and contributions as researchers, supervisors, teachers, collaborators, software developers, data managers, communicators, and community builders—as one single number.

Figure 2: It is exceptionally hard to win a football game with only strikers. Yet, academia still selects its team based on one single metric. Graphic from Crameri (2023).

So… Should We Use Another Metric? Or No Metrics?

Wrong question.

Instead of ranking academics, let us characterize them. The best team is diverse. The smartest distribution of funding is diverse. The strongest science is diverse. So, let us try to find the most suited person for the job, the project, or the team, in a way that does not waste the precious, mostly publicly-funded work time of the academic evaluators.

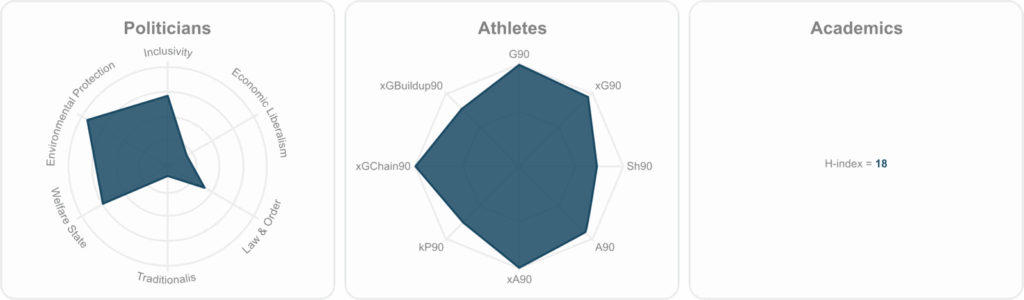

How do we do that? – If you take a step back and look at it, it is quite simple. We need to broaden the evaluation characteristics while maintaining the effective and objective nature of metrics. Today, an open and free-to-use visual academic profile based on multiple, incentive-focussed metrics offers a solution.

Meet ProAc – Your New Academic Spirit Animal

ProAc was thought up out of love to science and the people behind it, and ultimately built with a bit of fury. It is the result of mitigating that existential anxiety a year of unemployment brings along towards avoiding similar moments for others to come. The result is unapologetically honest in its rigorous and interest-free design and incorporates feedback from both scientists and evaluators.

ProAc is an incentive-focussed multi-metric academic profile that is scientifically grounded, transparent, and free to use. As a visual profile, it is an objective tool for time-effective and objective academic evaluation that represents much more of the full suite of skills and characteristics of the scientist.

ProAc is:

- Multi-dimensional: captures a fuller picture of you.

- Open-source: freely accessible to everyone, not just panel insiders.

- Visual and intuitive: usable by non-expert evaluators.

Instead of cherry-picking just the one trait, ProAc covers much more of the whole tree and paints a fuller picture of an academic’s traits and duties: it allows you to grow, not just compete.

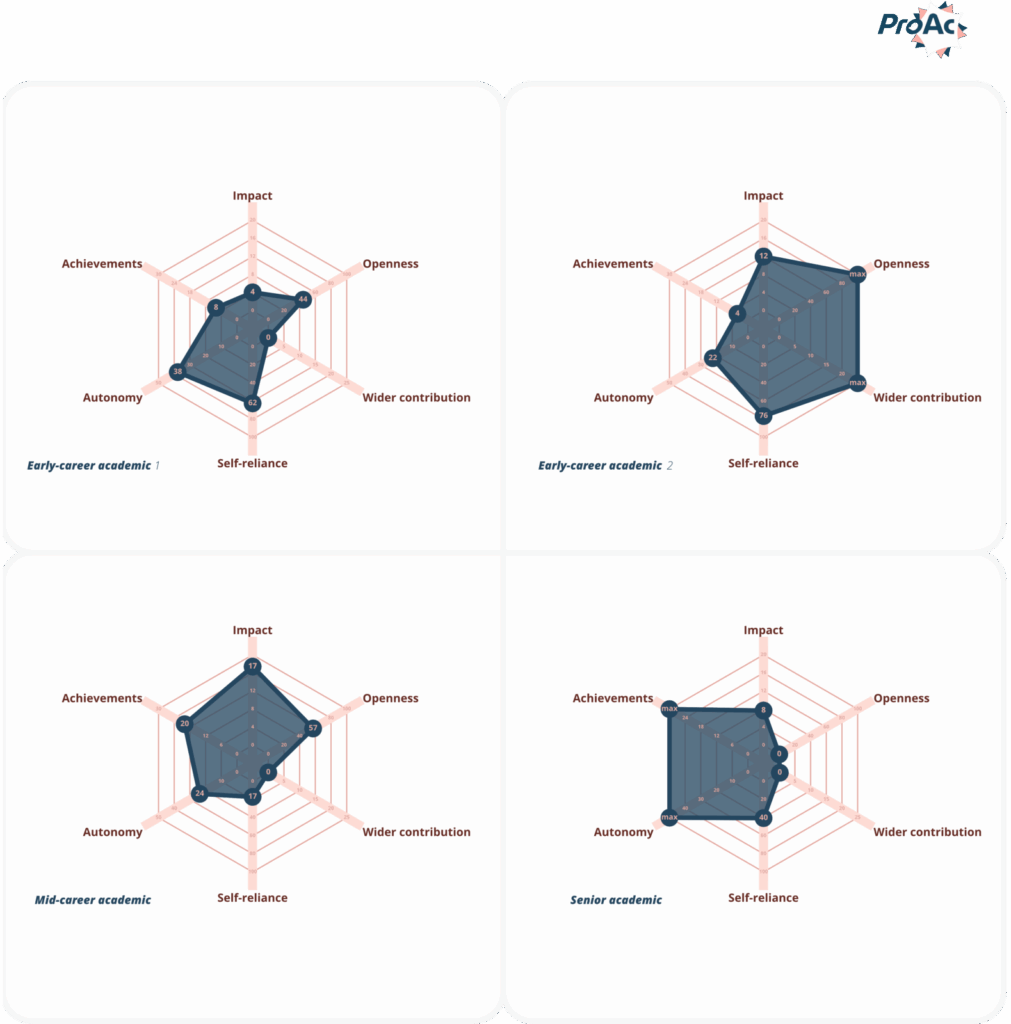

What ProAc Actually Measures (and Why That Matters)

ProAc tracks academic contributions that shape science and society beyond just peer-reviewed papers. The current version includes:

- Impact: citations per publication (age-weighted).

- Self-reliance: share of first-authored citations.

- Autonomy: impact minus PhD supervisor collaborations.

- Wider contribution: impact of non-traditional outputs.

- Openness: open-access ratio over five years.

- Achievements: total output and impact.

Besides scientific openness, this multi-metric profiling incentivises quality over quantity, collaboration over competition, and early-career innovation over established name-dropping.

Especially for You, Early-Career Researcher!

In particular as early career scientists, you deserve a fair and full reflection of your work, achievements, and skills. Scientific evaluation with ProAc fairly reflects career breaks, levels institute and supervisor inequalities, and rewards outreach, methods development, and openness—things that you care about, but the h-index ignores.

You are more than a citation count. ProAc is the first step towards showing your real academic self. It helps you highlight your true strengths, grow your weaknesses, and might even clarify where you could go. Additionally, and importantly, it enables you to breathe easier.

Figure 3: ProAc profiles are designed for purpose-focused evaluation—not ranking based on prestige. Can you guess the actual geoscientists behind these? Graphic from Crameri (2023).

Getting Started

All you need to get started with, is to fill in the spreadsheet (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7691086) with your academic data, and convert it to a visual profile using the online tool on fabiocrameri.ch/proac.

Redefining Success, One Profile at a Time

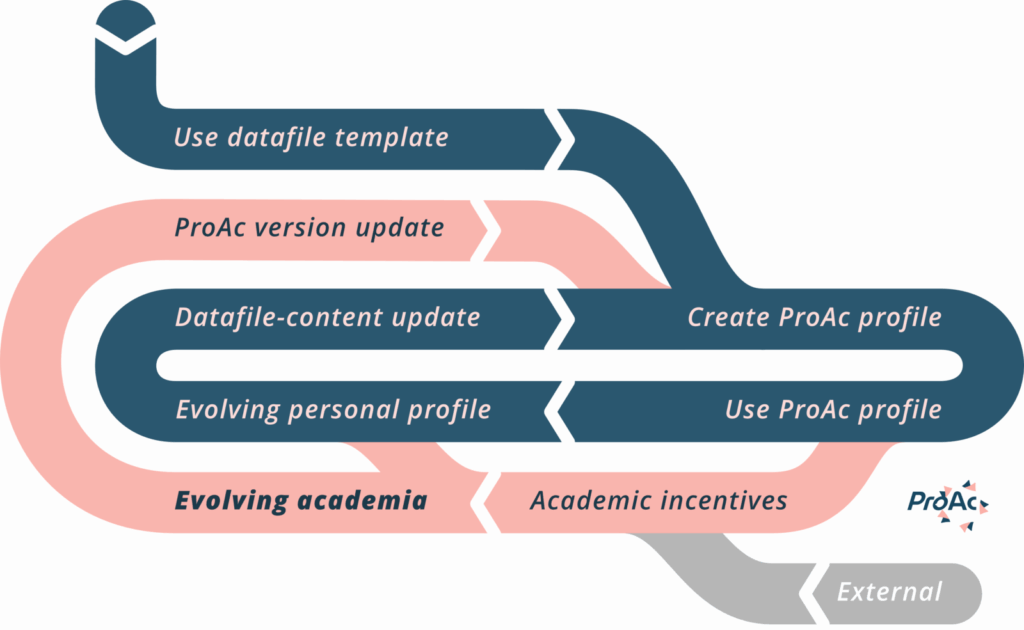

Figure 4: The ProAc Revolution. Empowering personal (dark blue) and academic (light pink) feedback loops maintained by continuous ProAc adjustments. Graphic from Crameri (2023).

Academia is tough. But tools like ProAc remind us it does not have to be soul-crushing. It can be reflective, empowering, and—dare we say—fun. The use of a well-designed academic profile is a small step that inflicts long-term improvement through the right incentives. On a personal level, seeing your academic character, rather than your ranking, in an unfiltered manner helps to appreciate and develop your individual academic self. It becomes easier to find the right team, job, and project. When individual academics strive to improve in diverse areas and not just peer-review publishing, science will prosper and academia will feel more like a wholesome football team, rather than a bunch of strikers fighting to get to the ball first.

Will we get there? – Just five years ago, we were laughed at when suggesting a virtual seminar talk. “Open-access journals do not exist and never will!”, was the tenor around that same time. And remember what spending time on that “unproductive” EGU Division blog post has brought us?

System-wide change always starts with small steps.

So, here and now, make your choice: you either let it fall, or you support inclusive, objective, and time-saving, profile-based academic evaluation—and an academia with the right incentives.

I made mine. Let us go, ProAc—for us and the ones to come.

Thanks for reading. 🫶

About author: Fabio Crameri is a science communicator and researcher working at the intersection of geoscience, design, and outreach. He is the founder of Undertone.design, where he creates science-grade visualizations and communication tools that are both accessible and aesthetically pleasing. His work is widely recognized for promoting colorblind-friendly and perceptually uniform colour maps in the Earth sciences. In addition to his freelance work, he collaborates with institutions such as the European Geosciences Union and the International Space Science Institute to advance science communication. Fabio has written several blogs for the EGU already about science, read them here:

- EGU22: Rethinking (geo)scientific conferences today

- Honest observations about EGU23 poster designs

- How many transdisciplinary researchers does it take to find out how an ocean sinks?

Would you like to follow Fabio further? You can find him at:

www.fabiocrameri.ch

Linkedin: http://www.linkedin.com/in/fabio-crameri

Bluesky: https://bsky.app/profile/fabiocrameri.ch

References

- Crameri, F. (2023), Multi-metric academic profiling with ProAc (1.0.0). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4899015

- Hirsch, J. E. (2005). An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(46), 16569-16572. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0507655102

This blog was edited by ECS members Katinka Tuinstra and Adam Ciesielski. Want to see more ECS activity? Follow us on LinkedIn and Instagram.

Would you like to write a blog for us? Or would you like to join the team? Contact us (EGU SM team) at LinkedIn and Instagram, or write an e-mail:

eguseismoblog at gmail dot com, or personally: adam dot ciesielski at igik dot edu dot pl or https://www.linkedin.com/in/a-ciesielski