When you picture sailing on a ship, what do you imagine? Cool breezes, salt spray, glorious sunrises, the peaceful sounds of breaking waves and passing gulls’ cries?

As it turns out, you can go for multiple days at sea without directly looking at, smelling, or hearing the ocean waves – at least, you can if you sail on a 71-meter-long marine seismic research vessel like the R/V Marcus G. Langseth.

I sailed on the Langseth on her most recent trip to the central Aleutian Islands, way out west from mainland Alaska. The purpose of the expedition was to collect marine active-source seismic data around a section of the Aleutians, to image crustal structure beneath the volcanic arc and learn more about magma storage and construction of the arc crust.

This was my first full-length research cruise, and in one sense no one could have told me in advance what to expect or prepare for. During the current COVID-19 pandemic, going to sea involves in-port quarantines, masks, temperature checks, and a host of other necessary precautions that are new even to more experienced mariners. But even on this not-so-normal research cruise, over the course of 39 days at sea, I feel like I got a sense of what it’s like to sail aboard a seismic research vessel. So, here’s a brief list about some of the peculiarities of marine life, through the eyes of a junior scientist and novice sailor.

Morning is a social construct

On Langseth, I woke up almost every day at 10:42 pm, made some toast in the mess for breakfast, and went downstairs to the main lab, where Donna and Cody wished me a good morning. Not long after midnight, I would wish each of them a good night as they finished their shifts and went off to sleep. And what is “a morning”, really, besides the time when you get up and start your day? Operations on the ship ran 24/7 and my watch was midnight to 0600, so for the duration of the cruise, I switched over to a quasi-nocturnal schedule and saw far more of the moon than the sun.

Weather is more than small talk

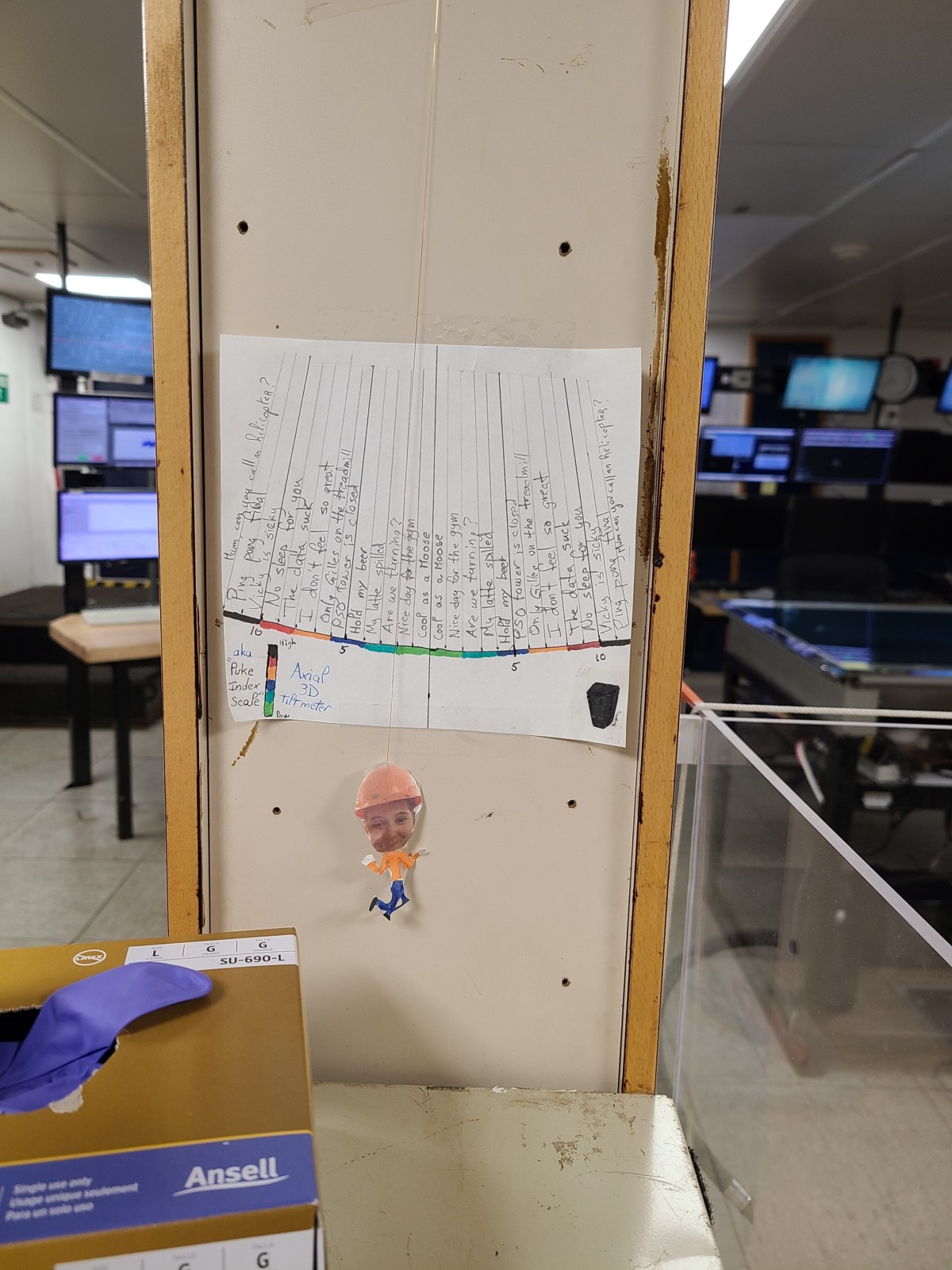

A handy low-tech tiltmeter in the main lab can help sailors gauge just how unpleasant rough seas will feel.

We sailed into the North Pacific in early September, just in time for fall storms to start cycling through the region. This mattered both for our personal comfort (rough seas can make it hard to sleep, or even walk in a straight line down a hallway) and for our ability to collect data safely. Crewmembers can’t work out on deck when huge waves are periodically crashing high over the rail, and towing the seismic source or streamer behind the boat in bad weather can be dangerous for both the equipment and the vessel.

All of that means that we talked about the weather pretty much all the time, checking forecasts and sea state predictions and continually adjusting the science plan to try and avoid the worst of the storms. Despite those precautions, we still ended up going through some pretty nasty wind and waves, and during those days I stayed entirely indoors on the little floating island called the Langseth. Also, I learned the trick of sleeping with one knee jammed against the wall of my bunk to keep myself from rolling around too much.

Ships are surprisingly noisy

Well, ok, maybe I’m the only one who was surprised that a large ship with diesel engines and air compressors and ventilation systems has a pretty high ambient noise level – and that’s before you account for reverberations from the seismic source when we were in shallow water, or the bow thrusters when the ship was using the dynamic positioning system to maintain a location. I found that I had to speak louder than I was used to if I wanted anyone to be able to hear me, particularly during the first two weeks of the cruise when we were all wearing masks.

There’s nothing quite as exciting as a brand-new dataset

For the first couple weeks, we scientists didn’t have much to do during our watches – over the course of six hours I might note some things in the log-book, but that was about it, since technicians and crew members did all of the highly specialized work of deploying and recovering ocean bottom seismometers, streamer and the seismic source. But once the data started to come in, we began to do some preliminary processing and got a first look at what promises to be an exciting dataset. We’ve only scratched the surface of what this refraction and reflection data have to show us, and I can’t wait to see what it will all look like after more thorough processing and analysis.

Many thanks to Captain Dave and the crew of the Langseth, all the OBS techs from Scripps and WHOI, and the LDEO marine office for making this cruise happen. For more info on the science goals and cruise life, check out the official cruise blog at https://donnajshillington.com/aleutians-field-blog/.

This cruise report was written by Hannah Mark

with revisions from ECS representative Maria Tsekhmistrenko.