When reading fantasy novels, we are usually brought to worlds of elves, dragons, and epic battles, all surrounded by breathtaking magical forests, or castles above impervious cliffs. However, even fantasy stories take inspiration from the real world and its geology. Who does not remember the ascent of Mount Doom of Frodo and Sam, or the importance of Dragon Glass (Obsidian) in Game of Thrones? So, let’s dive into some examples of the impact of geology in these fantasy classics.

Mount Doom

Let’s start with one of the most famous volcanoes of literature! While writing The Lord of The Rings, between 1937 and 1949, Tolkien probably followed the development of geological sciences at that time, particularly the continental drift theory, reflecting this interest in the evolution of Middle-earth and Arda (Hynes, 2012).

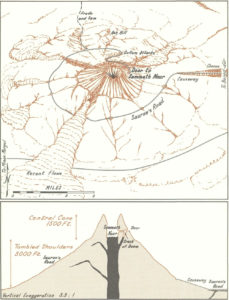

Mount Doom (or Amon Amarth) is described as a strato-volcano, the only one active in the Plateau of Gorgoroth; however, even considering the cinematographic image of Frodo and Sam climbing the mountain, it is not even reaching half the high of Mount Etna, with a maximum elevation of 1300 m! Moreover, the hobbits climbed the gentler slope, where no sign of recent lava flows was defined, as described by Karen Wynn Fonstad in “The atlas of Middle-earth”. Tolkien was (apparently) not inspired by any volcano, however, he commented on the similarity of Mount Doom to Stromboli volcano in Italy. Peter Jackson based the reprises for the movies on two active volcanoes in New Zealand: Mount Ruapehu and Ngauruhoe.

Recently, the new series of Rings of Power, the Lord of the Rings prequel (thousands of years before the adventure of the Fellowship of the Ring), showed us the origin of Mount Doom and Mordor, in a quite debated way. A huge amount of water flowed in tunnels built by the orcs, creating explosions through a village, reaching Mount Doom, and falling directly into it. This caused a massive eruption, destroying the land and creating Mordor. Probably, when the water entered in contact with the magma, caused a phreatomagmatic eruption. However, the amount of destruction which created Mordor needed great quantities of lava flows and cannot be associated with this kind of eruption (Washington Post).

Path of the Dead

On a more sedimentary and geomorphological note, another interesting feature is the Pūtangirua Pinnacles, once again in New Zealand. This formation is an example of badlands erosion, where conglomerates have been washed away by rainwaters, while others have been protected by cemented silt, creating these amazing pinnacles.

These features are partially visible during the “Return of the King” when Aragorn, together with Legolas and Gimli, walked the Paths of the Dead to summon the Army of the Dead to defeat the Orcs.

Game of Thrones, Westeros and Valyria

Now, let’s leave hobbits and elves, and let’s move to another fantasy saga, Game of Thrones! Maybe a non-geological eye doesn’t notice, but geology is fundamental in the development of the stories both in the books by George R. R. Martin (“A song of Ice and Fire”) and the TV series adaptation. For example, Dragon Glass, which is obsidian, volcanic glass, turned out to be central in defeating the White Walkers and was found in huge quantities in Dragonstone, a volcanic island and castle owned by the House of Targaryen. In real life, the castle used for filming is San Juan de Gaztelugatxe, Spain, which is made of hard reef limestone from the lower Cretaceous.

An important moment described partially in GoT is the Doom of Valyria. At first read, as a geologist, it was clear enough to me that what was described as “every hill for five hundred miles had split asunder to fill the air with ash and smoke and fire” was related to the catastrophic volcanic eruption of the Fourteen Flames. These were probably a supervolcano like Yellowstone or Campi Flegrei. It was also clear the occurrence of a tsunami following the eruption, maybe something like the most recent Hunga Tonga – Hunga Ha’apai which reach South American coasts. The eruption caused the fragmentation of the Valyrian peninsula and the creation of the Smoking Sea.

Dr Miles Traer did a terrific job reconstructing the main geological events that occurred in Westeros, creating an amazing geologic map. For instance, the sea dividing Westeros and Essos (the Narrow sea) is due to a breakup totally analogous to the spread of the Mid-Atlantic ridge.

Geological Map of Westeros, from Dr. Miles Traer

Generally, the geology of Westeros is associated with two different orogenic phases, the Moon Orogeny, and the Black Orogeny. The Mountains of the Moon can be compared to the Canadian Rocky Mountains in North America, and probably have formed in two stages, as proposed by Traer: an early subduction of a microplate beneath southern Westeros, and a continental collision between northern and southern Westeros. In this mountain range we can also find Casterly Rock, home of the House of Lannister and rich in gold deposits (citing Dr Traer interpretation):

“Gold is typically deposited on the ocean floor near mid-ocean vents. The gold mixed with the basalt (extrusive igneous rock) until it reached a subduction zone. As the oceanic crust that previously separated northern and southern Westeros subducted beneath the southern part of Westeros, layers of ocean rock were scrapped off (like a bulldozer), accreted onto the continent, and uplifted. The heat and pressure of subduction dissolved the gold, which then intruded into the overlying rock and solidified within quartz veins (this is where the gold from the California Gold Rush came from).”

…and behind the Wall

“Winter is coming” is probably the most famous citation of GoT, and is the motto of the House of Stark, ruler of Winterfell. This area is cold and has a subarctic climate, with general snowy winters and cool summers; so it is not unexpected that most of the filming took place in Northern Irland and in Iceland. The castle of Winterfell has also a natural hot spring, which helped to warm the castle, with actual geothermal heating.

This area is cold and has a subarctic climate, with general snowy winters and cool summers; so it is not unexpected that most of the filming took place in Northern Irland and in Iceland. In particular, in Iceland, the mixture of snow, glaciers and volcanic rocks was perfect to depict the Wall and the White Walkers’ land: for instance, Kirkjufell, or “Church Mountain”, is one of the most popular Iceland mountains, and although we are in the country of volcanoes, it is not a volcano itself. The mountain is constituted by volcanic rocks from Pleistocene lava and tuff on top, and the conic shape is caused by glacial erosion occurring all around, a shape called nunatak. Kirkjufell was chosen as the place where Night Walkers were created, and as a battle area for Jon Snow vs the Night King.

As you can see, even with these few examples, geology influenced the stories of those fantastic worlds. Hope you enjoy this quick tour!

Let us know if other geological elements have caught your attention, or if you know any other fantasy saga where geology is almost more important than the main character!

References

Hynes, G. (2012). ” Beneath the Earth’s dark keel”: Tolkien and Geology. Tolkien Studies, 9(1), 21-36.

Fonstad, Karen Wynn. The Atlas of Tolkien’s Middle-earth. Rev. Ed. London: HarperCollins, 1994.

Miles Traer website: https://milestraer.com/got-geology/