Words on Wednesday aims at promoting interesting/fun/exciting publications on topics related to Energy, Resources and the Environment. If you would like to be featured on WoW, please send us a link of the paper, or your own post, ERE.Matters@gmail.com

***

Citation: Scott, S., Driesner, T. & Weis, P. Geologic controls on supercritical geothermal resources above magmatic intrusions. Nature Communications. 6:7837 doi: 10.1038/ncomms8837 (2015)

Blog by Samuel Scott

Electricity production from high-enthalpy geothermal systems typically involves drilling boreholes into permeable reservoirs at depths of 1-2 km and temperatures between 250-300 °C. The fluid that comes up the wellbore consists of a mixture of liquid and vapor, from which the vapor is separated and passed through a steam turbine to generate on average 3-5 MW per well. The Iceland Deep Drilling Project (IDDP) was founded by a group of international scientists who sought to drill to deeper, hotter conditions where water is a single-phase, intermediate density, supercritical fluid. Basic thermodynamic considerations suggest that wells drilled into supercritical geothermal resources could potentially provide an order of magnitude more electricity than a conventional geothermal well. A plan was developed to drill a borehole to 4-5 km depth in the Krafla geothermal system, with the aim of discovering a reservoir at supercritical temperatures (>374 °C) and pressures (>220 bars).

Transparent, opalescent steam discharges from the IDDP-1 borehole at the Krafla volcano in Iceland. (Image: Kristján Einarsson/IDDP)

Drilling was difficult and did not go as expected. After chunks of quenched glass began to come up the wellbore, they knew that they had drilled into a magmatic intrusion located around 2 km depth. Studies of the glass showed that it was rhyolitic in composition. Temperature measurements suggested a fluid temperature as high as 450 °C, but since the intrusion was encountered at a relatively shallow depth, the fluid pressure was less than the supercritical pressure, and the fluid was categorized as ‘superheated steam’. The big surprise was the fact that the fluid reservoir was nonetheless much more powerful than typical wells drilled to 2 km depth. As can be seen in videos taken during the well testing (https://vimeo.com/28453850), the well discharged large volumes of translucent and opalescent fluid – classic indicators of a supercritical fluid. Well tests indicated that the well could potentially generate 35 MWe of electric power, roughly an order of magnitude greater than a typical geothermal well. However, there were many questions that surrounded this discovery. How did this fluid reservoir form? How could it form at such a shallow depth? It was unclear whether the IDDP reservoir was an anomaly, or whether similar resources could exist in other high-enthalpy systems.

This led myself and a group of collaborators at ETH Zurich to use numerical models to understand the hydrology of the IDDP reservoir. The computer code had already been successfully applied to understand high-temperature fluid flow in other settings, such as mid-ocean ridges and the formation of copper-rich porphyry deposits. We set-up the model such that only a few key parameters were needed, aimed at capturing the main sources of geologic variability between different geothermal settings. The key data that go into the model are the depth of the intrusion, the host rock permeability (a measure of how fractured the system is as a result of tectonic activity) and the brittle-ductile transition temperature (which determines the temperature where rock becomes impermeable due to plastic deformation closing connecting fluid flow pathways).

code had already been successfully applied to understand high-temperature fluid flow in other settings, such as mid-ocean ridges and the formation of copper-rich porphyry deposits. We set-up the model such that only a few key parameters were needed, aimed at capturing the main sources of geologic variability between different geothermal settings. The key data that go into the model are the depth of the intrusion, the host rock permeability (a measure of how fractured the system is as a result of tectonic activity) and the brittle-ductile transition temperature (which determines the temperature where rock becomes impermeable due to plastic deformation closing connecting fluid flow pathways).

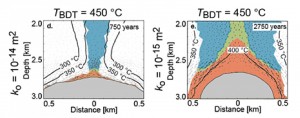

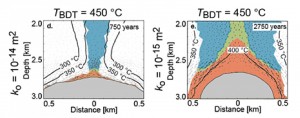

These models show how these primary geologic controls determine the extent and thermal conditions of supercritical reservoirs. For example, our study identified a brittle-ductile transition temperature greater than 450 °C as a key control on reservoir formation. Since basalt has a brittle-ductile transition temperature >450 °C, while granite becomes impermeable around 360 °C, we expect that the best resources will be found in basaltic rocks. Additionally, if the rock surrounding the intrusion is very permeable, we expect the supercritical resources to be close to the intrusion, relatively limited in spatial extent, and at temperatures near 400 °C. If the rock surrounding the intrusion is moderately permeable, the reservoirs will be larger and at higher temperatures. However, the fluid production rate for a well drilled into a supercritical reservoir will be higher when rock permeability is higher. Thus, there is a trade-off between fluid temperature and well productivity that is governed primarily by rock permeability. These basic concepts can inform future efforts to discover and exploit these resources.

If the rock (white) surrounding an impermeable body of magma (grey) is only highly permeable, supercritical water (red) is restricted to a thin layer around the magma (left panel). However, if the rock is moderately permeable, a large area can be heated to supercritical conditions (right panel). (Illustration: from Scott et al. 2015, Nature Comm.)

Our models were able to reproduce measured data from the IDDP well when the geologic controls are set to appropriate values for the Krafla system. This supports the model set-up, as well as the conclusion that supercritical geothermal resource properties depend on geologic controls. Moreover, the models show that conventional geothermal resources result simply from the mixing of supercritical fluids ascending from the intrusion and cooler fluids circulating near the intrusion but not heated to supercritical conditions. This is a new way to look at conventional high-enthalpy geothermal reservoirs.

In future studies, we will seek to better understand the role of supercritical water in controlling the thermal structure and temporal evolution of high-enthalpy geothermal systems. As our understanding progresses, we will move towards modeling specific geologic settings, including the Reykjanes geothermal system where the next IDDP well will be drilled. Since the Reykjanes geothermal field contains groundwater that is known to have a large seawater component, fluid salinity is likely to play a key role on supercritical resource formation and properties. Salt changes the thermodynamic properties of water such as density and viscosity and allows boiling to occur at higher temperatures and pressures than for pure water. This may affect the formation of similar supercritical reservoirs in unexpected ways.

Although this was not the outcome the IDDP expected, the fact that such a reservoir was encountered on the first intentional effort suggests they may be a common feature that we have been passing up by targeting reservoirs at shallower depths. It also means that targeting supercritical geothermal resources may be even more economically attractive than expected by the IDDP, since wells do not need to be drilled as deep as expected. Exploiting supercritical water resources has the potential to massively improve the economics of power production from magma-driven geothermal systems. Time will tell whether or not they can be found in systems all over the world, but we anticipate that the search for these fluid reservoirs will continue.