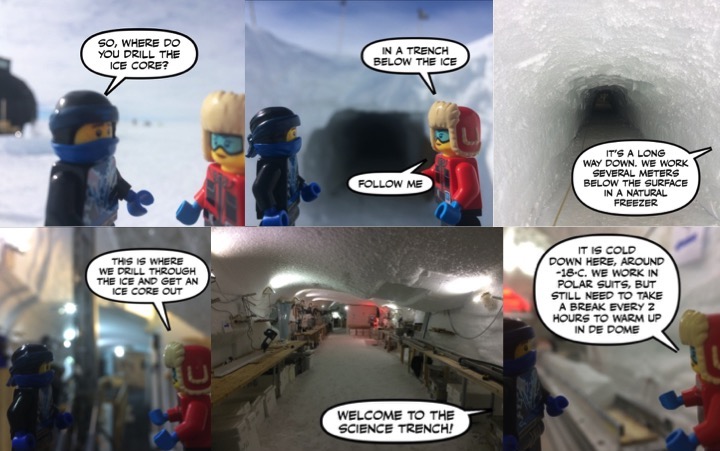

How do you get there? Where will you sleep? What work will you do there?These are just a few of the many questions I got from family and friends when I told them that I would join the EastGRIP ice core project this summer. As a paleo climate and ice sheet modeller, I could only repeat the abstract information given to me, very conscious that I actually had no idea how it would be to live and work on top of the Greenland ice sheet. In the numerical models I use for my work, the ice sheet shape and properties are represented by numbers and mathematical equations. Quite different from the vast expanse of empty, flat whiteness around the EastGRIP camp. Inspired by my kids (two boys who love to play with LEGO and watch Ninjago) I took a LEGO ninja and a LEGO scientist with me to the field. I wrote a little scenario involving a villain, a ninja who accidently ends up in Greenland and a scientist. Their adventure is my attempt to describe the travel, life and work in the ice core drilling camp. It became a 94-picture story in comic book format. The full story can be read here, but let me show you some of the highlights.

The travel

For example, I explained that we travelled from Kangerlussuaq on the west coast of Greenland to EastGRIP by military plane. These special planes can land on normal runways, but also have skies in order to land on EastGRIP’s runway made of compacted snow.

The camp

In the camp, most of us sleep in bunk beds in heated tents. Apart from scientists and drillers, there is also a medical doctor, a cook and a mechanic in camp. These people are essential for keeping the camp running, safe and in a good mood. The population in camp varies between about 20 to 40 people, depending on the workload and time within the field season. Being at EastGRIP is a bit like camping on the snow. Even the toilets are located in tents.

The work

The primary activity at EastGRIP is of course related to drilling an ice core. In a large trench below the ice, several “rooms” have their own specific purpose, the largest ones are for the drilling and processing of the drilled ice. The latter happens in the “science trench”, where each bench has its own specific tools to either cut the ice or measure properties of the ice. In a conveyer belt-like system, scientists process the drilled ice at a rapid tempo.

The science

Of course, at some point the LEGO ninja wonders why we actually drill these ice cores. The LEGO scientist explains the basics of preserving climate information in layers of snow. Layers are compacted and become the ice we drill, with the climate information archived inside.

Why are we drilling a deep ice core at EastGRIP? [Credit: Petra Langebroek – Map data Credit: Google]

The EastGRIP ice core is being drilled at the start of the North East Greenland Ice Stream (NEGIS). This is the largest ice stream in Greenland, and it is still unclear how it exactly originated and why it is there. The surface velocity at EastGRIP is around 51m/yr, which is extremely fast for ice far inland. The main objective of the EastGRIP project is to study the dynamics of this ice stream, both internally in the ice and at its base.

In the end of the LEGO adventure, the ninja knows everything about EastGRIP and upon return to Bergen, captures the villain!

– The End

Further reading

- Check-out the entire EastGRIPninja adventure on https://flic.kr/s/aHsmEbKWfz

- More on the EastGRIP Project: https://eastgrip.org/About.html

Edited by Violaine Coulon

Dr Petra Langebroek is a senior researcher at the Norwegian Research Centre NORCE and the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, in Bergen, Norway. She works with ice sheet and climate models, aiming to understand past changes in ice sheets and climate. Currently she is coordinating a strategic project at the Bjerknes Centre (https://rises.w.uib.no/) focussing on the interactions of Greenland Blocking, ice dynamics and basal hydrology, using geological information from the Scandinavian Ice Sheet as an analogue for future Greenland changes. She is also coordinating the freshly started Horizon 2020 project TiPACCs (https://www.tipaccs.eu/) on tipping points in the Southern Ocean and Antarctic Ice Sheet.