Women make up 50.8% of the worlds population, yet fewer than 30% of the world’s researchers are women. Of this percentage, BAME (Black Asia and Minority Ethnic) comprise around 5%, with less than 1% represented in geoscience faculty positions.

The divide between women in the population and women in STEM needs to be addressed. Through a series of blog posts we hope to raise the voice of women in the cryosphere community, and spread awareness of the amazing work they do.

This Women of Cryo blog post aims to outline the status of women in cryospheric sciences in Chile, where the statistics are unfortunately no better than worldwide, but changes are slowly happening. Stay tuned to learn more about the women working on the South American Andes in Part II of this blog!

Introduction

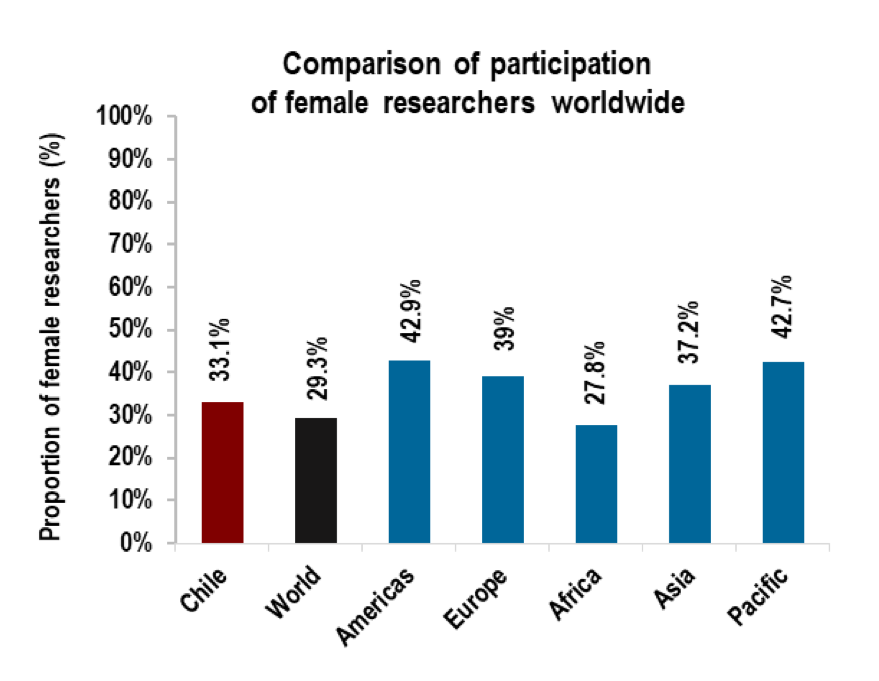

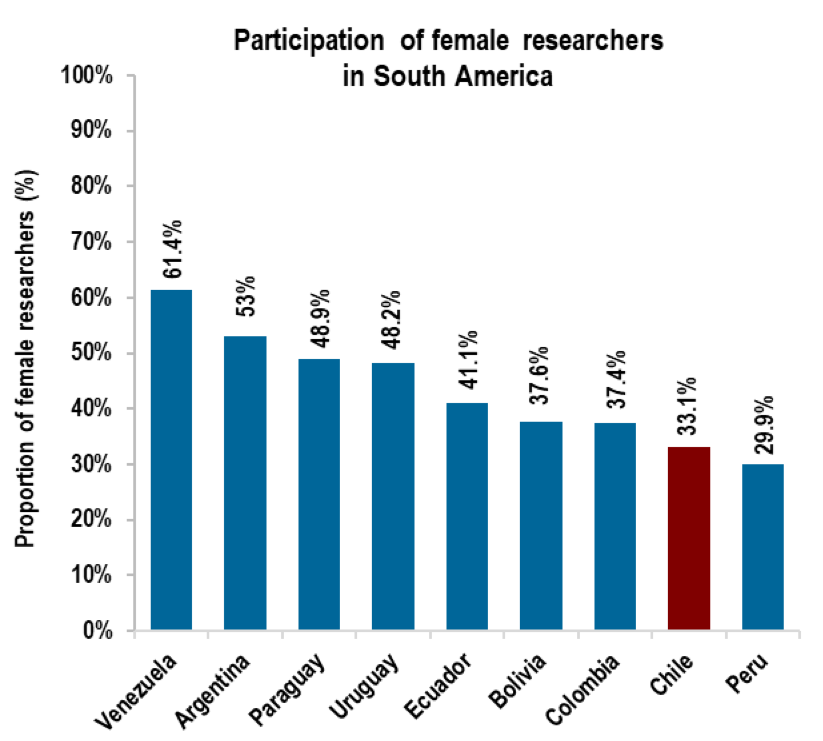

Women in science scarcely represent 30% of the world’s researchers according to the UNESCO Institute of Statistics. In addition, gender stereotypes, the “leaky pipeline phenomenon”, sexual harassment in academia, and the fieldwork involved, are some of the reasons as to why women in science remain underrepresented [a,b,c,d]. In Chile, gender imbalance in science mirrors the international context (Figure 1), even though the Americas has been recognised as a region where women’s representation in science has increased compared to other countries of the world, and female representation reaches 42.9% [e,f]. However, Chile still has one of the lowest ratios of women participating in STEM (33.1%) (Figure 2) and is followed by other countries in the Americas, such as Mexico and Peru [g].

Figure 1. Participation of female researchers in STEM as a percentage of the total number. Data is presented in headcounts as the total number of people employed in Research & Development (R&D). Some data is also based on estimations. [Credit: Paola Araya & Helena Valenzuela-Astudillo, based on UNESCO Institute of Statistics (2019) data repository].

Figure 2. Participation of female researchers in STEM in South America as a percentage of the total number. Data is presented in headcounts as the total number of people employed in Research & Development (R&D). Some data is also based on estimations. [Credit: Paola Araya & Helena Valenzuela-Astudillo, based on UNESCO Institute of Statistics (2019) data repository].

Figure 3. Paola is using Flubber to model San Quintín piedmont glacier (North Patagonian icefield) with senior elementary students (2015) in Villarrica, La Araucanía region, Southern Chile as a key activity to encourage young girls and boys to understand these physical systems. [Credit: Paola Araya].

Gender equity in the Cryospheric Sciences in Chile

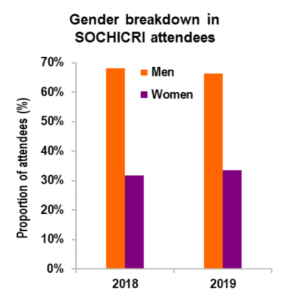

Using data from the SOCHICRI [j] annual meetings (The Chilean Society of the Cryosphere), we took a look at gender equity in the cryospheric sciences in Chile from attendees of the 2018 [k] and 2019 [l] annual meetings.

A previous article [m] in the EGU Cryosphere blog looked at the gender diversity in the cryosphere sections of two of the most important non-profit international organisations in the fields of Earth, atmospheric, ocean, hydrologic, planetary and space sciences: the European Geosciences Union (EGU) and the American Geophysical Union (AGU).

Their approach was to identify those members that had been asked to select their salute (Mr vs Ms/Msr) when they first registered. Following a similar methods, we took a look at how SOCHICRI compares to these much larger groups. As salute data was not available for the SOCHICRI attendees, our method leans heavily on a binary classification based on the sex of the attendees’ first name. There is therefore the chance that we have not been able to discern gender accurately for some attendees.

Two aspects should be kept in mind when looking at the results of our gender breakdown of the SOCHICRI attendees for the 2018 and 2019 our study (Figure 4). Firstly, these numbers only account for attendees who have filled out and paid for registration. Secondly, and perhaps, more importantly, we understand that this classification can exclude those individuals who identify themselves outside of the binary gender spectrum.

Figure 4. Gender breakdown in SOCHICRI attendees’ data for 2018 and 2019. The numbers presented are valid as of 09/24/2021. [Credit: Paola Araya & Helena Valenzuela-Astudillo, using SOCHICRI data].

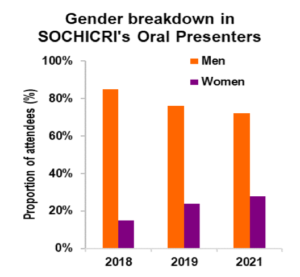

Figure 5 shows gender breakdown in SOCHICRI oral presenters for the 2018, 2019, and 2021 annual meetings. Women make up 15%, 24%, and 28% respectively, which account for less than a third of the total participation in all SOCHICRI’s oral sessions. However, there is an encouraging positive trend being shown for women’s participation year to year, hopefully indicative of a permeant increase in women’s participation. It should be noted that men’s participation is declining as women’s participation is rising as the oral sessions have a limited number of participants for each event.

Figure 5. Gender breakdown in SOCHICRI oral presenters’ data for 2018, 2019 and 2021. The numbers presented are valid as of 09/24/2021. [Credit: Paola Araya & Helena Valenzuela-Astudillo, using SOCHICRI data].

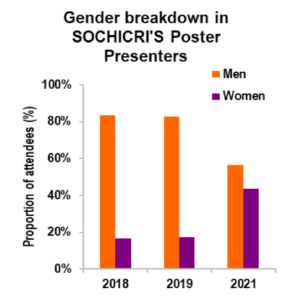

Figure 6. Gender breakdown in SOCHICRI poster presenters’ data for 2018, 2019 and 2021. The numbers presented are valid as of 09/24/2021. [Credit: Paola Araya & Helena Valenzuela-Astudillo, using SOCHICRI data].

According to our analysis of the gender diversity at in SOCHICRI, there are clear signs of increasing participation of women in cryospheric research-related activities in Chile, which is really encouraging to see. Although, it is important to note that the field of glaciology at the national scale in Chile still lacks in gender diversity. In this context, we recognise some limitations that have played a role in preventing diversity in glaciology. For instance, our country poses as one of the Southern Hemisphere hotspots for research and education in glaciology since approximately 3.1% of its territory is covered by ice (with the Patagonian icefields representing the third-largest ice-covered area after Greenland and Antarctica!) However, for decades there were no glaciology-oriented departments or academic programs within the Country. As such, Chile experienced ‘Brain drain’ (the emigration of highly qualified people) of its glaciologists, who were forced to pursue the subject overseas.

Nowadays, we recognise the responsibility that national institutions such as the Chilean National Agency for Research and Development (Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo de Chile in Spanish) have for collecting demographic information on who is working in the cryosphere sciences. Their goal is: “to link necessary resources to the minoritised populations that currently lack them and to identify the resources required to succeed at various career stage so that we can build on-ramps outside of the traditional academic pipeline”, an aim originally proposed by the CryoCommunity (United States).

In part 2 of this blog post, we will introduce some of the women working in glaciology in the South American Andes who have managed to overcome the obstacles in place for women working in the cryosphere. By narrating a few of their stories about the work they carry out on the southernmost tip of the South American continent, and how they live for these glaciers, we hope to highlight the importance of women’s work on glaciers.

Further reading:

[a]. Blickenstaff, C. (2005). Women and science careers: leaky pipeline or gender filter?, Gender and Education, 17(4), 369-386

[b]. Goulden, M., Mason, M. A., & Frasch, K. (2011). Keeping Women in the Science Pipeline. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 638(1), 141–162.

[c]. Moss-Racusin, C., Dovidio, J., Brescoll, V., Graham, M., & Handelsman, J. (2012). Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109 (41) 16474-16479.

[d]. Clancy, K., Nelson, R., Rutherford, J., Hinde, K. (2014). Survey of Academic Field Experiences (SAFE): Trainees Report Harassment and Assault. PLoS ONE 9(7): e102172.

[e]. UNESCO Institute of Statistics (2015).

[f]. Espinoza, C. (2019). Mujeres en ingeniería y ciencias: un tercio productivo y diferenciador. Beauchef Magazine-Especial Mujeres.

[g]. UNESCO Institute of Statistics (2019).

[h]. Hulbe, C.L., Wang, W., & Ommanney, S. (2010). Women in glaciology, a historical perspective. Journal of Glaciology, 56, 944 – 964.

[i]. Koenig, L., C. Hulbe, R. Bell, & D. Lampkin. (2016). Gender diversity in cryosphere science and awards. Eos, 97.

[j]. SOCHICRI (Sociedad Chilena de la Criósfera. Chilean Society of the Cryosphere in English):

[k]. SOCHICRI’s registered attendees’ data (2018)

[l]. SOCHICRI’s registered attendees’ data (2019)

[m]. Case, E., Coulon, V., & Isaacs, F. (2019). Bridging the crevasse: working toward gender equity in the cryosphere. EGU Blogs.

Edited by Emma Pearce & Marie Cavitte

Paola Araya holds a B.Sc. in Geography from the Catholic University of Chile and is a MSc Student in Meteorology and Climatology at the Geophysics Department of the University of Chile where she focused on modelling projections of glacier change along the 21st Century for the Maipo River Basin, central Chile, located to the east of the Chilean capital city, Santiago, providing most of its drinking water.

Helena Valenzuela-Astudillo holds a B.Sc. in Geography from the University of Chile. Her undergraduate research focused on the study and geomorphic characterization of rock glaciers at the Yerba Loca Sanctuary, an important basin near Santiago.

Paola and Helena are volunteering members of the NGO Fundación Glaciares Chilenos where they are working on the project ““Entre Mujeres y Glaciares”” (pages 20-21) (“Between Women and Glaciers” in English part of multiple initiatives promoting women’s contribution to cryospheric sciences using STEM, art, literature, sports and activism. They tweet as @martianglaciers and @helenas_va, and can also be contacted through their respective emails, pparaya@uc.cl and helena.vastudillo@gmail.com.

NGO Fundación Glaciares Chilenos is a non-profit organization that works for the protection of glaciers located in Chile. Our mission is to educate and communicate about glaciers in our national territory. By articulating collaboration with different sectors within society such as academia, civil society, and local settlements that depend on glaciers, either economically or as a vital resource for human development, we pursue raising awareness about the importance of glaciers in the context of environmental stewardship and protection. In order to address the complex issue of glacier protection, NGO Fundación Glaciares Chilenos focuses on three main activities: educating the Chilean population about glaciers, making the topic more visible, and providing accurate and comprehensible information about glaciers through effective science communication. We are always welcoming new members into our organization, come on and join us!