Contributed by Nir Krakauer nkrakauer@ccny.cuny.edu

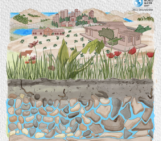

Does water fall if no one hears it? It does. Invisible water flows slowly under the ground, in soil and rock, downhill or from wet to dry areas. This groundwater eventually surfaces at rivers, springs, swamps, and other water features. As rivers and lakes get tapped out or polluted, more groundwater is being pumped out for irrigation and industrial uses, hurting the animals groundwater flow sustains.[1] Yet we still know little about how far and fast groundwater flows.

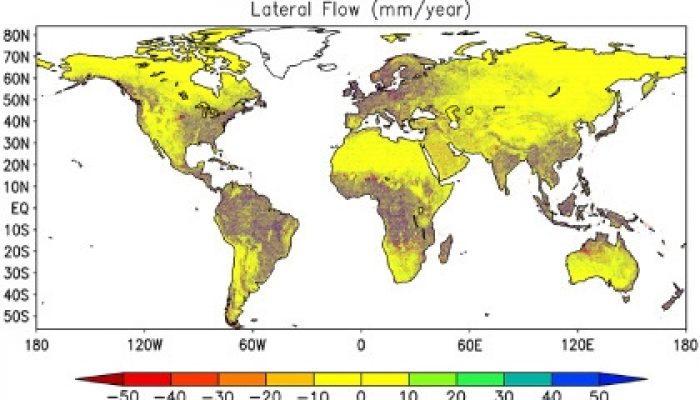

In my team’s work, we trace the flow paths of groundwater in two ways. First, we consider the geometry of the paths groundwater must follow from its origin as rainwater and what that implies about the amount of groundwater that typically flows in or out of regions of different sizes. Second, we simulate groundwater flow in each continent based on detailed surface height maps from satellites. We mapped the likely groundwater flow directions and rates under natural conditions (no pumping). With this baseline, we expect to better determine how groundwater pumping impairs water flows and ecosystems.

One implication of this study has to do with how scientists simulate climate. Models run on computers to forecast weather and project climate changes currently ignore groundwater flow pathways. We find that the amount of water conveyed by groundwater flow is significant over path lengths of up to several tens of kilometers. The resolution of global and regional climate models is now becoming good enough to resolve these flow paths, and we are beginning to explore how such groundwater flow affects cloud and rainfall patterns.

This article is the first in a series of plain language summaries on Water Underground. This article and others will be put through the 5upgoer word processor to test for the 1000 most common words in the English language…almost half words in this article that aren’t this list including importance, groundwater and climate… from the title!)

Christopher Duffy

I fully agree that groundwater is an important missing element in our understanding of climate and has important implications in ultimately developing fully integrated water cycle codes that predict at “useful” scales for critical water problems. One of the major missing building blocks is high resolution hydrogeologic data. I know that this is changing (e.g. the author of this blog) but it seems that funding agencies have not yet realized the potential of this critical data resource.

Pingback: Groundwater extraction can move mountains | Water Underground