Volcan Villarrica from the air in 2009.

Villarrica (Ruka Pillan in Mapudungun) is one of the most active volcanoes of southern Chile, and is a popular tourist destination in the heart of the Chilean Lake district. Villarrica has been in a continuous state of steady degassing for much of the past 30 years, since the last eruption in 1984-5, and began showing signs of increased unrest (seismicity, and visible activity in the summit crater) in February 2015. Eruptive activity at Villarrica in 1963-4 and 1971 was characterised by vigorous ‘Strombolian’ explosions from the summit – typically with short paroxysms of fire fountaining – followed by the formation of lava flows. The major hazards at Villarrica come from the lahars, which form as a result of the melting of snow and ice from the summit glacier by the intruding or erupting magma. In 1963 and 1971 the lahars that swept off the volcano caused considerable damage, and a number of fatalities in the affected areas.

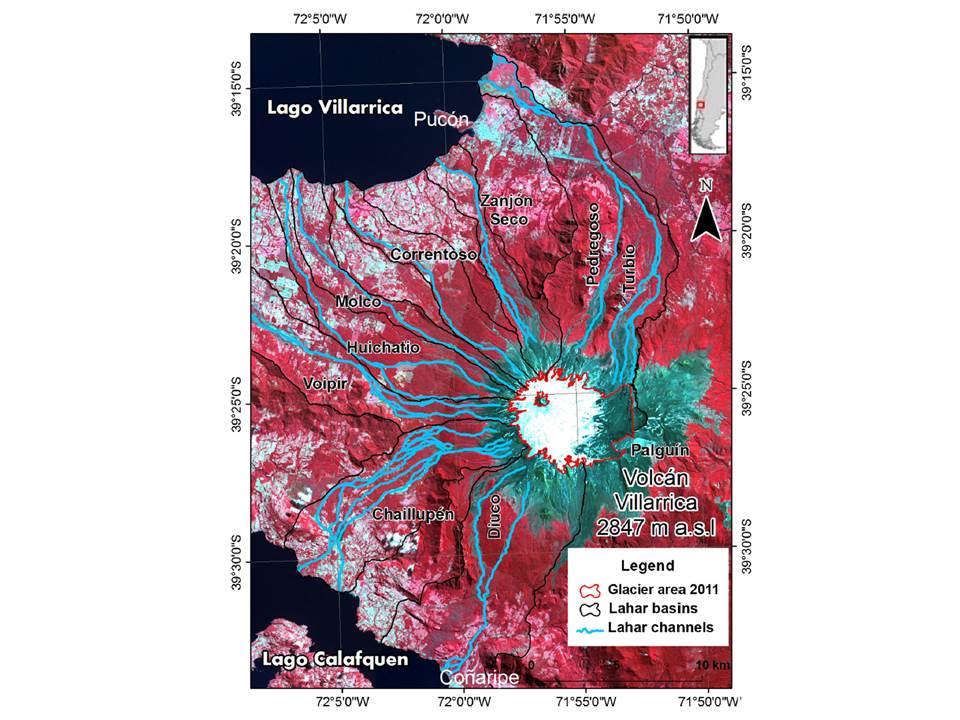

At the present day, the volume of ice in the summit region is a little over 1 cubic kilometer. Any melt waters and lahars that may form as a consequence of the volcanic activity are expected to drain along any or several of the nine major lahar channels that were either active during the past eruptions of Villarrica, or have been identified from fieldwork and mapping. Recent work on the sediments from Lake Villarrica show that the transport of volcanic ash into the lake by lahars forms a very clear record of the small eruptions of the volcano that would otherwise not be preserved.

Map showing the nine major lahar channels (in blue) that drain off the summit of Villarrica, The area outlined in red shows the extent of the summit glacier field in Februiary 2011. The main tourist resort of Pucon, and lake Villarrica, lie to the north. In 1964, lahars caused much damage to the village of Conaripe, to the south. Map from Rivera et al. (2015) , lahar channels from Castruccio et al. (2010).

The first Strombolian paroxysm from the 2015 eruption was reported shortly after 3 am local time on 3rd March; and this was followed by reports on social media of spontaneous evacuations from some of the communities that have been affected by lahars in the past. The Chilean agency responsible for civil protection (ONEMI, Oficina Nacional de Emergencia del Ministerio del Interior y Seguridad Pública) declared a ‘red alert‘ shortly afterwards, and SERNAGEOMIN also raised their technical ‘volcanic alert’ level to red. If the current phase of activity follows the pattern of past eruptions, there may be an extended period of elevated activity with intermittent paroxysms over the next few days to weeks.

This paroxysm just lasted a few tens of minutes, but released large puff of ash that rose to about 9 km above sea level and could be seen on geostationary weather satellites; a burp of sulphur dioxide that was visible from space, and coated the summit of Villarrica with a fresh coating of volcanic ‘spatter’. On the volcano itself, there was clearly some melting of snow and ice, and small amounts of volcanic ash were washed down the local drainages, and into Lake Villarrica.

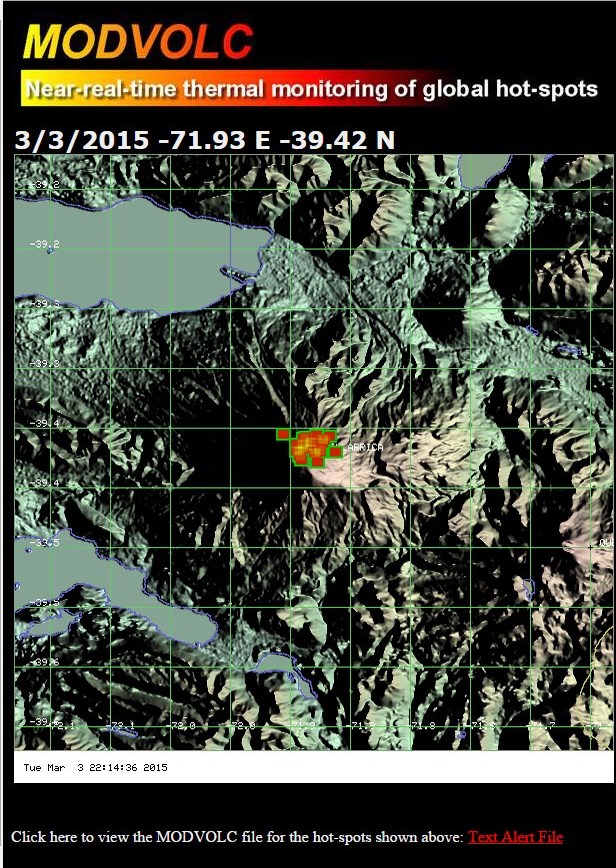

The footprint of the ‘hotspots’ associated with the freshly deposited ejecta can be seen in the alerts detected by University of Hawaii’s MODIS Thermal Alert System, using imagery from the MODIS sensors onboard NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites.

Screen shot of the ‘thermal alerts’ detected by the HIGP MODIS Thermal Alert System for Villarrica, on 3 March 2015.

Update – March 5th, 2015.

The eruption was over quite quickly, and although a few thousand people evacuated at the time, most returned home later that day. Flights over Villarrica by the volcano monitoring and civil protection teams on March 3rd, and subsequent days, showed that the summit vent became sealed by fresh spatter during the eruption, but signs of activity diminished very quickly. SERNAGEOMIN reported that only one monitoring station was lost during the eruption, and their current scenario is that there may be some intermittent weak Strombolian activity in the near future, which should be readily detectable on the monitoring systems. Photographs posted on social media showed only little evidence for limited damage by lahars during this first eruption; including damage to a tourist centre on the volcano slopes.

Ongoing Activity

Latest status reports from ONEMI, Chile

Latest status reports from SERNAGEOMIN, Chile

Latest webcam images of Villarrica, from SERNAGEOMIN

Latest Volcanic Ash Advisories from the Buenos Aires VAAC

Further information

Great video footage of the 3rd March eruption from 24Horas

Collections of photos and video from BioBioChile, 24Horas, Cooperativa, the Guardian and SERNAGEOMIN.

Villarrica on Volcano Top Trumps

Villarrica pages at the Smithsonian Institution Global Volcanism Programme.

References

Castruccio, A. et al., 2010, Comparative study of lahars generated by the 1961 and 1971 eruptions of Calbuco and Villarrica volcanoes, Southern Andes of Chile, Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 190, 297-311.

Rivera, A. et al., 2015, Recent changes in total ice volume on Volcan Villarrica, Southern Chile, Natural Hazards 75: 33 – 55

M van Daele, J Moernaut, G Silversmit, S Schmidt, K Fontijn, K Heirman, W Vandoome, M De Clercq, J van Acker, C Wolff, M Pino, R Urrutia, SJ Roberts, L Vincze, M de Batist, 2014, The 600 yr eruptive history of Villarrica volcano (Chile) revealed by annually laminated lake sediments, Geological Society of America, Bulletin doi:10.1130/B30798.1

Pingback: Taking the pulse of a large volcano: Mocho-Choshuenco, Chile | volcanicdegassing

Obat kuat perkasa paling ampuh

Thanks for your valuable information. It really gives me an insight on this topic. I’ll visit here again for more information.