August 27th marks the anniversary of the culmination of the great eruption of Krakatoa (or Krakatau) in Indonesia in 1883. This devastating eruption has become the archetype of a volcanic catastrophe, even though it was a geologically modest example of a ‘caldera forming’ event. The eruption of Krakatoa quickly made the headlines around the world, in part because newly installed undersea cables allowed the news of the event to be wired rapidly across the globe.

Precursory eruption of Krakatoa in May 1883, several months before the climactic events of August 1883. From Symons (1888).

The Krakatoa eruption was one of the first major eruptions to be intensively studied by scientists. The journal Nature published an editorial explaining the ‘Scientific Basis of the Java Catastrophe’ shortly after news of the eruption broke, and over the next few weeks published reports with the first descriptions and explanations of some of the many widespread effects of the eruption – from the appearance of great floating rafts of pumice, to the many oceanic, atmospheric and other phenomena that accompanied the event. In February 1884, the Royal Society set up the Krakatoa committee, chaired by a meteorologist George Symons, to collect information on ‘the various accounts of the volcanic eruption.. and its attendant phenomena’, including ‘authenticated facts respecting the fall of pumice and dust .. unusual disturbances of barometric pressure and sea level.. and exceptional effects of light and colour in the atmosphere‘. These results were published in 1888 in a wonderfully illustrated monograph, which still stands as one of the most complete accounts of a major volcanic eruption and its widespread effects.

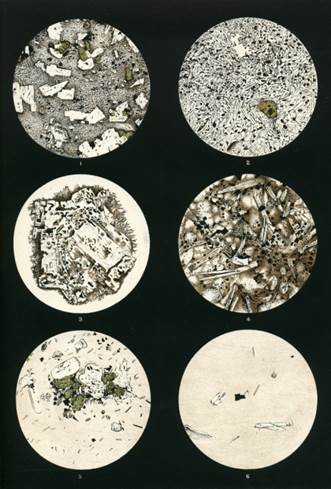

Drawings of microscope views of Krakatoa rock samples in thin section. This set of images are of lavas from Krakatoa, from Symons (1888). These are quite rich in crystals (white feldspar; green pyroxene), set in a fine matrix of glass (colourless to brown). Images on the left: about 1 cm across; on the right – about 1 mm across.

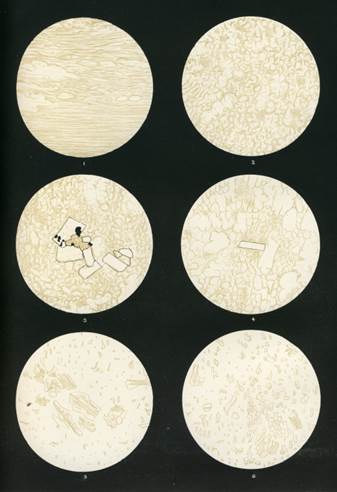

Drawings of microscopic images of 1883 Krakatoa pumice and ash samples . The pumice samples are mainly made of glass (very pale colour) with gas bubbles. The top 4 images are each about 1 cm across, and show the texture of lumps of pumice. The bottom two images are each about 1 mm across, and show the ‘ash’ that fell over a thousand miles away from Krakatoa on the ship Arabella (left), and the ‘ash’ formed by grinding up a sample of pumice. From Symons (1888).

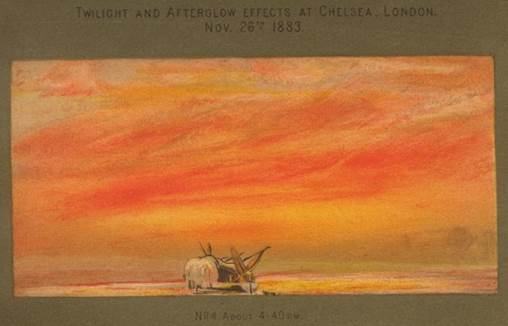

The most celebrated impact of the Krakatoa eruption in terms of science was the recognition that the many optical effects that followed the eruption, including both spectacular sunsets (an example from London, in November 1883, below) and the discovery of ‘Bishops’ Rings‘, must be the consequences of the global spread of volcanic pollutants, high in the atmosphere. We now know that the major constituents of this haze were tiny droplets of sulphate, forming a thin aerosol layer in the stratosphere which scattered and absorbed incoming solar radiation.

Although the Krakatoa eruption was one of the largest eruptions of the past 200 years, it is not exceptional in comparison to other eruptions from the geological record. In terms of eruption ‘size’ it rates as a ‘6’ on the Volcanic Explosivity Index, having erupted an estimated 12 cubic kilometres of magma. Eruptions of this sort of size occur once every 100 – 200 years around the globe; while the largest known explosive volcanic eruptions erupt many thousands of cubic kilometres of magma over a very short period of time. Krakatoa remains the best documented example of a ‘caldera-forming’ eruption, during which an entire volcanic edifice collapses. In this case, the eruption and the formation of the caldera had catastrophic consequences for tens of thousands of people along the shores of Java and Sumatra, as a series of major tsunamis triggered by these events swept ashore.

Reference

G.J. Symons (Editor, 1888), The eruption of Krakatoa and subsequent phenomena. Report of the Krakatoa Committee of the Royal Society. London : Trübner & Co.

Links to some other posts on Krakatoa

David Bressan’s excellent post for the Scientific American Blog

Bill McGuire’s post on Krakatoa for the OUP Blog

Jeremy Plester’s Weatherwatch piece for The Guardian

Cynthia Wood’s post for Damn Interesting

A page on the Krakatoa eruption from the United States Geological Survey

Pingback: Morsels for the mind – 30/8/2013 › Six Incredible Things Before Breakfast

Pingback: ‘An amazing and portentous summer..’ | volcanicdegassing

iiiii

The eruption of volcano is causing major destruction in Indonesia. And this event is known around the world.

Pingback: Volcanic lightning during the 1902 eruption of St Vincent – londonvolcano

Pingback: GeoLog | Extraordinary iridescent clouds inspire Munch’s ‘The Scream’