In a post two months ago, I promised that I’d keep you updated with how my research is progressing. Needless to say, I’ve done a pretty poor job of that, unless you follow me on Twitter! I must apologise – the workload while travelling was severely under-estimated, and I’ve barely had time to catch a nap. I’m writing to you now from Lyon, where I finally had a day off in about a month to explore the Basilica and Roman amphitheater ruins here, and am now nestled in a snug pub hammering away at a manuscript!

The last time I wrote about le research was in Berlin, I think, where the specimen Theriosuchus ibericus resides, along with a possibly new species of Alligatorellus. These are both atoposaurids, or dwarf crocodiles – the former from the latest Cretaceous of Romania, the latter form the infamous Solnhofen beds from the Late Jurassic of Germany.

Maxilla, or cheek bone of Theriosuchus ibericus. That big tooth is pretty odd, and not seen in English specimens of Theriosuchus.

A lot has happened in the meantime. I visited New York City, my first ever trip to the USA and American Museum of Natural History, to compare some of their specimens housed there with the li’l atoposaurids, which was quite a fruitful experience. They have there the holotype, or specimen which a taxonomic name was constructed on, of one of the earliest crocodylomorphs called Protosuchus, which was neat, as well as a whole throng of dinosaurs! Heinrich Mallison was there too, scanning some oviraptorid dinosaurs, and he blogged about them here.

The Society of Vertebrate Palaeontology held its annual meeting in Los Angeles immediately after this visit (I did three pretty rubbish blog posts about the content here). There was no wifi available at the conference part of the venue, so the live-communications was pretty tame by comparison to other conferences. Palaeocast did cover a lot of the content, but even they were restricted in what they were allowed to cover. I should note that, due to personal disagreements between myself and the founder of Palaeocast, combined with some rather ‘personally aggressive’ comments on his half, I have now left Palaeocast, and am no longer involved in any of their activities. However, I wish them well as a project in the future, especially as they recently took on Laura Soul as part of the team.

Following this, there was a really useful course in Bristol about using the Palaeobiology Database, the software PAST (Palaeontological Statistics), and the programming language R for advanced statistical analyses (have a play with some palaeo data and scripts here). I didn’t really take any notes from this, as it was rather intensive, but hope to provide some insight into their use in the future. Richard Butler, Al McGowan, Mark Bell, and Graeme Lloyd did a fantastic job for the 3 days as course moderators, and are thanked greatly for their time and expertise. I guess the main cool thing about the workshop is that it demonstrates the willingness, and indeed activity, of palaeontologists into taking their science to the next level, with ever-larger datasets and more intricate analyses.

On the brief stop back in the UK, myself and Eva Amsen also ran a session at this years SPoTON London conference geared around online science communication. Eva chaired a panel discussion about whether or not the way we communicate science needs to adapt, and how should it if so, in a world where open access publications are increasing the access (but not necessarily the accessibility) of scientific research. The storify of the event is here, and if you have any thoughts or comments about this, please do drop them below!

Barcelona was next on the tour, to visit the specimen Montsecosuchus depereti. This atoposaurid used to be called Alligatorium, like some of its French and German cousins, but was renamed, and after a detailed analysis of the specimen, rightly so! It was a bizarre micro-croc, and I revised its status to give it a more robust taxonomic definition. This means that it’s definitely a valid species, and as the jewel of the Catalunyan collections, I’d hope so!

Complete skeleton of Montsecosuchus depereti, with classic ‘splat syndrome’. The skull to body length ratio for this beasty is weird compared to the other specimens I’ve seen..

I’ve never been to Eastern Europe before. Romania was a world apart from any place I’ve ever been, and it was even weirder as almost no-one spoke English, unlike a lot of the more ‘touristy’ locations visited previously. Nonetheless, they had an important atoposaurid specimen there, called Theriosuchus sympiestodon, from the island archipelago that was Romania some 66 million years ago, and home to a number of dwarfed dinosaurs. There wasn’t much of it, just a partial skull, but I’m not sure if it belongs to Theriosuchus, or represents a new species of atoposaurid. New material of this species is to be published soon, but a look at that manuscript (super secret atm, sorry), doesn’t change my thoughts on this. It would make more sense to that an animal living so long after it’s generic counterparts would be an entirely new animal too.

Theriosuchus sympiestodon, the maxilla too but from the inside (medial). Check out the difference between the teeth compared to Theriosuchus ibericus above.

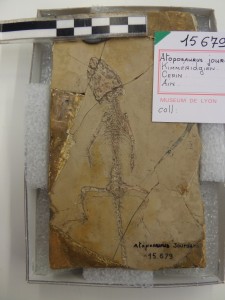

The final stop, and why I come to you from Lyon, was a massive puzzle piece to fill in ze research. There were SIX atoposaurid specimens in the collections here, all from Cerin in France. My battery is about to die. Two specimens of Alligatorellus beaumonti, supposedly the same as those in Munich, a specimen of Alligatorium meyeri, complete with its counterpart specimen, and two of Atoposaurus jourdani, a teeny tiny croc!

After careful analsyses, I have some preliminary conclusions:

- Alligatorium is a badass li’l croc, and definitely a valid species

- Alligatorellus from France is distinct from the Munich specimen, and probably a new species

- Alligatorellus from Berlin is also entirely distinct, and probably a new species too

- Atoposaurus probably is a juvenile species of Alligatorium or Alligatorellus, but which one..?

Atoposaurus jourdani. It really is that tiny. An awesome pet to have 150 million years ago! What do you think – juvenile, or teeny dwarf?

I’m currently writing a manuscript to describe the middle two of these points, and will have a pre-print up asap. There’s a specimen called Atoposaurus oberndorferi housed in the Teyler’s Museum, Netherlands, I need to check out early next year, also from Solnhofen in Germany. If it too is a juvenile, it’ll unfortunately make Atoposaurus an invalid genus, probably just a younger Alligatorellus, and may also cause issues for the name Atoposauridae. Oops. The reason for this is that they really are small, just about 8 inches long, and don’t have any of the body armour that characterises the other atoposaurid specimens. However, the rest of the skeleton does look quite mature, so they might have just lost this as they dwarfed in size.

As well as this, there are several lesser-known specimens to check out still, Theriosuchus guimarotae from Portugal, Karatausuchus sharovi, currently in Moscow, and Brillanceausuchus babourensis, in some tiny town in the middle of France that’s impossible to get to. These specimens have received so little attention, which is odd given that they may be really important in deciphering the evolutionary relationships of atopoaurids, and the origins of the group that would eventually give rise to modern crocodiles. Neat eh!

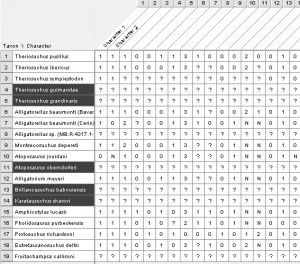

So all of this is feeding into the development of what we call a character matrix. This is a way of describing differences in anatomy between different species, or specimens, which we can run through a program that will give us an evolutionary hypothesis about the relationships between them. A screenshot of how this looks is below. Questions marks mean data is missing, which is actually quite a lot for atoposaurids just because of their squished mode of preservation obscuring a lot of the detail. ‘N’ is where a certain character state, or variable aspect of morphology, is not applicable. Zeros and ones describe the different aspects a particular feature can be.

Work in progress! The 5 bottom ones are called ‘outgroups’ – non-atoposaurids that we use to calculate the direction of change in each character. The four highlighted ones are ones I need to code still.

So this is it for now! I’m also working on two additional papers – one is the ruminant snout one I’ve been working on for waaay too long, but is at the final hurdle, and the other is a gigantic review paper of the Jurassic/Cretaceous boundary, which will essentially form my literature review section of the thesis (yes, do publish this part as a review paper!!). Either way, all of this will be available in pre-print format in the near future. Hope this all sounds interesting enough! 🙂

Pingback: To bird or not to bird.. | Green Tea and Velociraptors