Every culture has myths and legends about their native lands. Before we understood the geological forces that forced up great ranges of mountains or sculpted barren deserts, humans needed an explanation for the scale and majesty of natural phenomena. Stories of deities inhabiting volcanoes, or angry gods shaking the very ground upon which people lived, helped people make sense of disasters when tectonic forces were unimagined. Since the advent of the scientific method, and secularised science, such tales are often forgotten when we look at a landscape; why resort to a story when the facts say otherwise?

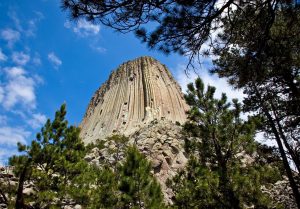

Devil’s Tower, Wyoming. Image courtesy psaudio / Pixabay

In some cases, it’s true that such stories don’t offer geologists much factual evidence about how the landscape formed. Even beautiful stories about features like the Devil’s Tower, in Wyoming, USA; the ancestral tale tells of people pursued by a giant bear; once they had reached the top of the peak, the bear could not reach them, but the scratch marks on the sides were testament to its attempts. Today, we know these are classic examples of columnar jointing. Although we might enjoy the story, it definitely doesn’t tie to the more modern understanding!

But there are some instances where we should perhaps pay more attention to myths, and particularly in the context of geology and sustainable development. While the tangible evidence of geological processes are often visible at a grand scale, it’s also true that the signals or proxies we look for to understand these processes can be very scarce. Trace fossils, or small shifts in element abundances, for example; we should take advantage of every shred of evidence we can find. As a result, some scientists have been turning to ancestral stories – in particular those about catastrophic events – for information.

Researchers have found tantalising clues about past events in mythical tales, and it seems often there is no smoke without fire. Amongst other studies, geologists have found evidence of volcanism in previously thought-dormant Pacific Volcanoes from local accounts, and evidence of giant floods in China, partly linked to tales of Emperor Yu 4000 years ago. The cultural memory of such giant catastrophes is etched into the myths told there; it seems that using these stories could help us better establish the timing and recurrence of natural disasters, allowing for improved risk analysis and development in tune with natural events.

There’s another, perhaps even more important aspect of geological myths to bear in mind for sustainable development. It’s increasingly well understood that the best approaches taken to encourage development, economic or otherwise, will differ across the world, driven by cultural differences. Development anthropologists could point to studies (e.g. see here) indicating that the definition of quality of life varies widely to suggest that a local approach would be the most sensible in approaching development, rather than assuming a standard ‘western’ approach would work everywhere.

The relationship of people to their landscape is, for the same reasons, an important variable to consider when discussing development. For example, Mt Machapuchare in Nepal is of special significance to Hindus, and as such is off-limits to climbers (and indeed has never been summitted). It is not the only mountain steeped in myth in the Himalayas, and as such, it would be a mistake to assume that the burgeoning tourist industry could operate freely on every mountain. Similarly, the recent decision to ban tourists from climbing Uluru in Australia may not make economic sense, but consideration of cultural associations clearly is more important.

Some of these cases may seem isolated. But every culture has its own unique relationship with land, which is to some degree (big or small) influenced by myth and legend. Applying the same development strategy in each setting is misguided – and to me it seems this is particularly true for the modern concept of treating the landscape as a commodity to be exploited for profit. Indigenous peoples (in Canada, for example) have treated the land they depend on in a highly sustainable fashion, informed by their cultural memory of fables and myth. We may not be able to return to such a state of living in the modern era, but if we want to build a more sustainable economy and change our current ‘business as usual’ model, it would be fitting to look to those cultures that have achieved a sustainable fashion of living – and particularly fitting to ask ourselves what about their cultural memory encouraged them to live that way.

Robert Emberson is a science writer, currently based in Victoria, Canada. He can be contacted via Twitter (@RobertEmberson) or via his website (www.robertemberson.com).