Boom & Bust in the Namib Desert

Namibia is mostly desert. Like its neighbour South Africa, the country was gifted with diamond-bearing Kimberlites. The Sperrgebiet (or “forbidden territory”), where the diamonds are concentrated, is strictly off-limits to the public. Namibia’s natural resources have played an important role in shaping the development of this inhospitable landscape.

Rumours of diamonds began trickling out of Namibia towards the end of the 19th century, but the isolated, underpopulated region remained under most people’s radar. It wasn’t until 1908 that a man called August Staunch, who managed part of a railway line running through the Namib desert, took a punt and asked his men to keep an eye out for shining stones. When one of his workers dutifully presented him with a rough diamond, he snapped up the licensing rights to the area without delay. His decision turned out to be very sensible indeed.

The Kimberlite pipes that carried the ancient gems up from deep in the Earth’s lithosphere have been weathered away by howling desert winds, leaving diamonds glinting across the red sand. Staunch’s area turned out to be teeming with undiscovered diamonds; a man could strike it rich by simply crawling around on his hands and knees in the moonlight.

One of the only roads to infiltrate the sand dunes runs to a small port called Luderitz. The town is a lone beacon on this stretch of treacherous coastline, dubbed “the gates of hell” by Portuguese sailors. Following the diamond discoveries, Luderitz became a boomtown. The stock exchange was housed in the Kopp Hotel and the barmaids were paid in diamonds when the cash ran out. The Germans moved in and built a bowling alley, shortly followed by a gymnasium and a ballroom. Water was shipped from Cape Town by the ton to feed the artificial oasis. The hospital also boasted Namibia’s first X-Ray machine – although it was primarily used for catching diamond smugglers. There seemed to be no end to the flow of diamonds from the sands.

World War I may have seemed a world (or at least a hemisphere) away from here, but the resulting slump in global diamond sales had a damning effect on this party in the desert. Just as the industry was beginning to recover, World War II hit, and superior reserves were uncovered further south. The death warrant of the Sperrgebeit was finally signed when the company headquarters were transferred to Orangemund in 1943.

The boomtowns became ghost towns, abandoned to the march of encroaching sand dunes. Standing testament to the glory and greed of the boom years, these towns now draw in the odd tourist, and Brian Cox (he flew into Kolmanskop ghost town to make some spurious link between sand dunes and the second law of thermodynamics in his globetrotting BBC series!)

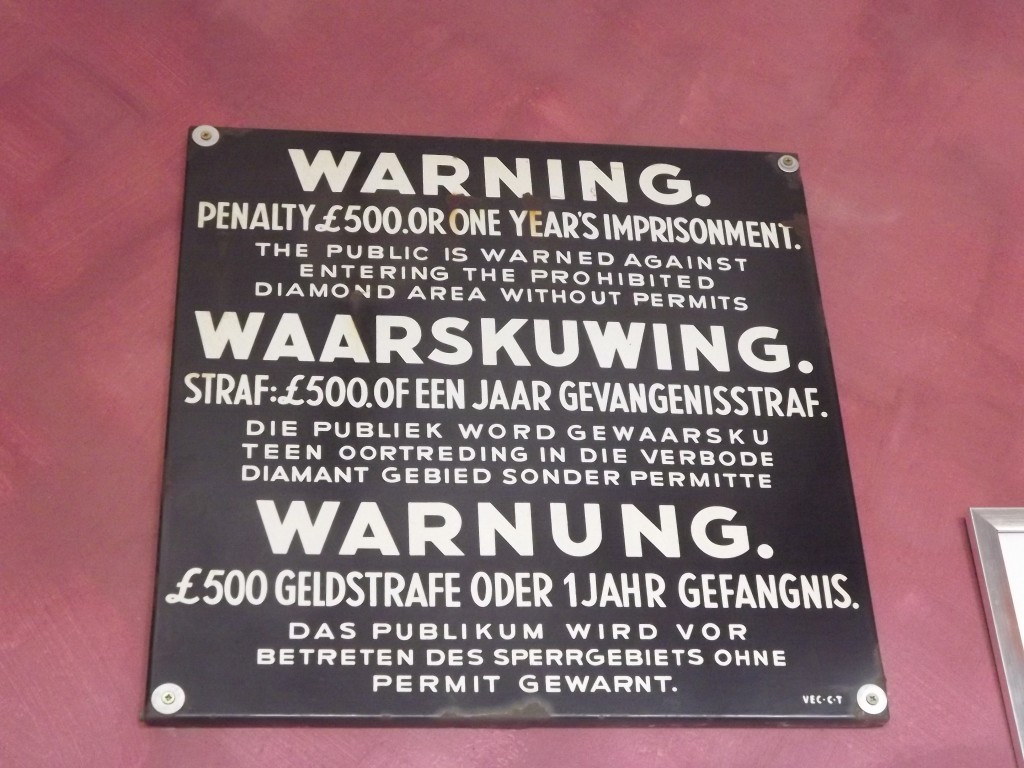

The rights to the region now belong to NAMDEB – a company jointly owned by the Namibian government and De Beers Ltd. The remaining diamonds are easy to find, so the region is still closed to the public – trespassing is met with a not insignificant £500 fine or one year’s imprisonment (your choice!).

The diamond industry has left the region both scarred but spared of over-use. Most of the Sperrgebiet is simply acting as a ‘buffer zone’, and so remains largely untouched. The areas where the diamonds occur, however, have suffered considerable damage. Some of the open-pit mines are being re-vegetated, and it looks like the area will slowly open up to tourists in the coming decades, providing new opportunities for a no longer forbidden Sperrgebiet.

Lab Lemming

Does Namibia actually have any diamond pipes of its own? I thought all the diamonds were weathered out of the Botswana and South Africa mines and carried to the coast by the Orange River.

Rosalie Tostevin

This may be the case for the diamonds around Orangemund, but I think the diamonds further north, around Luderitz, originated in the Namibian Gibeon kimberlite province.

Pingback: Climate and Policy Roundup – January 2014 | Four Degrees