It is only the first day and my diary is already jam packed! There is so much on offer at the conference that I’ve found it difficult to choose how to organise my day. However, I followed some of the tips on Will Morgan’s blog: Conference Top Tips for EGU2014: 1)Chat to people – check; 2) keep up to date with goings on in social media – check; 3) spread my wings- check. I must admit, I’ve failed at keeping a note pad handy and it has proven to be a real problem!

It is only the first day and my diary is already jam packed! There is so much on offer at the conference that I’ve found it difficult to choose how to organise my day. However, I followed some of the tips on Will Morgan’s blog: Conference Top Tips for EGU2014: 1)Chat to people – check; 2) keep up to date with goings on in social media – check; 3) spread my wings- check. I must admit, I’ve failed at keeping a note pad handy and it has proven to be a real problem!

Today my mission was to fully embraced number three and spread my wings by attending sessions not related to my research. It is easy to stick to your discipline and focus on only research you think might be relevant to your own. However, the range of topics on offer at the conference means it would be foolish to pass up the opportunity to investigate and learn about new topics!

The lab at Liverpool has strong links with archaeologist and so the session on artefacts and historical sites ( GI3.4) caught my eye. What struck me the most about what I learnt there is how applicable many of the techniques I thought were classically geological can be applied to archaeology. It shouldn’t be such a big surprise to me that you can use XRF (X-Ray Fluorescence) and SEM (Scanning Electron Microscopy) to characterise tiles on buildings and how the findings can help understand the effects of air pollutants can have on ceramics used on buildings. I was even more surprised to learn that electromagnetic waves (THz frequency in particular) are used on artworks to characterise classics such as Goya’s Sacrifice to Vesta. The methodology can identify defects on the canvas, how many layers the painting is made of and where the painter has applied more strokes.

The second highlight of my day was the Splinter Meeting on Natural Hazard Education, Communication and Science Policy-Practice-Interface ( SPM1.47). I found the discussion to make some very interesting points about how communities affected by natural hazards might respond and perceive scientist efforts at science communication, engagement and outreach:

- What is the impact of public communication on research?

- How much time should research projects (and scientists) dedicate to dissemination?

- Should funding bodies give more support and guidance into how to disseminate research findings and who the target audience should be? I think this point is valid, not just for the natural hazard community, but the research community in general, especially as outreach/public engagement is now a requirement for most successful grant applications.

- It is critical to make your science relevant to the audience you want to engage.

- We discussed in some detail what the role of web/social media vs. hardcopy vs.human interaction in public engagement is and someone raised the very valid point that it shouldn’t be one versus the other, but a far more combined approach.

- Finally, who should fund scientist efforts to engage in public education and communication?

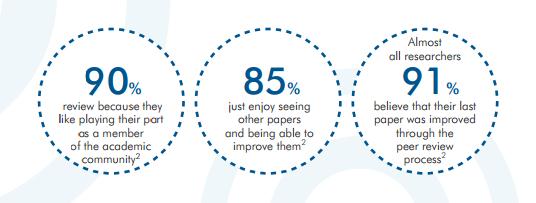

I also attended a medal lecture by Rumi Nakamura on Plasma Jets in the near-Earth’s magnetotail. I’m not going to lie, the most amazing fact I learnt at the talk was that Dr. Nakamura has published over 200 peer-reviewed articles which have been cited in excess of 4000 times! That is seriously impressive!

My day ended with the short course on Adding Value to Your Research Experience, but I’ll summarise the details of all the short courses I attend at the assembly into a single post after the conference, so keep tuned for that.

A diverse and very interesting first conference day.