Well, it has been a while since either of us has produced a GeologyJenga post, so first of all apologies on this front. We both have the same excuse – finishing our PhD theses! Our mutual deadline was 30 September 2014, and thankfully we both made it. The last few months were challenging at times and we both agreed that the feeling upon submission is hard to describe: certainly wonderfully joyous, coupled the tremendous relief, but tinged with no small amount of surrealism! We intend to put together a more comprehensive piece in the near future outlining the positives (and negatives) of our PhD experiences as well as suggestions and advice for those who may be at an earlier stage (or indeed approaching the end), but we thought it might be nice to precede that with a ‘welcome back’ post about our current activities and prospects.

A much shorter review of flood stratigraphies in lake sediments

Earlier this year my PhD supervisors and I (Daniel) had a paper accepted for publication in Earth-Science Reviews entitled ‘Flood stratigraphies in lake sediments: A review’ (Schillereff et al., 2014). It’s been fairly popular in terms of downloads but it occurred to me the other day that many of those prospective readers may be put off somewhat by its hefty word count. Thus, putting together a shortened version outlining the main points and conclusions seemed wise!

The review stems from my PhD research investigating whether sediment cores extracted from UK lakes contain distinct layers deposited by severe floods that occurred in past decades or centuries. It follows many neat papers illustrating similar case studies from every continent bar Antarctica. (We’ve included a KML GoogleEarth file in the Supplementary Info enabling users to fly to the sites of each published palaeoflood record mentioned in the text).

10 Minute Interview – The new Science of Geocognition

We are back! After a few weeks without posting, we thought it was about time we blogged! I have a HUGE backlog of 10 minute interviews that I have to transcribe from EGU 2014. The General Assembly was a great place to meet lots of young scientists doing all sorts of diverse and extremely interesting research. I’ve already posted a couple of interviews I carried out at EGU 2014 (you can read the one with Cindy Mora Stock here and the one with Young Scientist Representative Sam Illingworth here), but there are many more to come.

Today is the first of those! I had the huge pleasure of meeting the lovely Hazel Gibson at EGU. We’d ‘met’ on twitter and I was a huge fan of the content she shares on the social media platform. A girl after my own heart, she is big into science communication and outreach :)! Talking to her was fascinating, her research is focused on the up and coming discipline of geocognition which is how people perceive and understand Earth Sciences. Think psychology meets Earth Science. Importantly, it explores how your background (are you a knowledgeable audience, e.g. a geology researcher, or a non-expert. e.g. a member of the public) affects how you perceive the importance and relevance of Earth Sciences. I wasn’t able to attend Hazel’s talk at the conference, which was hugely disappointing, so I can’t give you more details. However, if you are keen to learn more, Hazel’s excellent blog is a good place to start!

- You are: Hazel Gibbson

- You work at: Plymouth University

- Your role is: PhD – 2nd Year.

Q1) What are you currently working on?

I study what people understand about geology, from a psychology perspective: known as geocognition. It combines geology and psychology by looking at how different audiences understand Earth Sciences. A key point is, how do professionals, academics and the public (including policy makers and teachers – it s a broad audience and can be broadly divided between an expert/non-expert audience) communicate and perceive Earth Sciences.

Q2) What is a typical day like for you?

My time is mostly spent in the office; I spend a lot of time interviewing participants and transcribing interviews. I have to construct the interview results into a visual interpretation of what is in interviewees head. In a sense, I have to try and create a model of what they are thiking. I also spend a lot of time working on outreach at the university. I have recently been involved with the Lyme Regis fossil festival. To take part in that I’m having to travel straight from EGU to festival.

Q3) Can you provide a brief insight into the main findings of your recent paper/research?

I am presenting an oral presentation at the EGU 2014 Assembly on Public Perceptions of geology. At the moment geosciences literacy models are used to build communication, if any models exist at all. But initial findings suggest that they don’t go far enough when comparing expert and non-expert perception of Earth Sciences because they are too logical and simplistic. When compared to a public model you get a lot of differences, not necessarily because the public’s model is wrong but because they haven’t had the training, so their mental models are different and structured differently, so it is misleading to think they are not logical.

Q4) What has been the highlight of your career so far? And as an early stage researcher where do you see yourself in a few years time?

I attended the unconventional gas conference and won a prize for her poster! This was a great achievement because the conference was mainly Industry lead. Presenting a poster on public perceptions of the subsurface to such a technically audience and wining a prize for it was very rewarding.

I would like to continue researching this field because it is a growing field. There is currently, lots of discussion from geoscientist about the importance of public understanding of Earth Sciences but not very much formal research. This means there are lots of avenues you can go down in this field, such as teaching. In the future I see myself teaching at Universities.

Q6) To what locations has your research taken you and why?

My research based in South west of the U.K. so I spend a lot of time in Devon & Cornwall particularly. These areas were chosen for my research due to there being a strong historical geology link, as the area used to be heavily mined and there are lots mining traditions which still remain. An interesting question I am trying to address is how does the cultural identity affects people’s perceptions of Earth Science?.

Q7) What is your highlight of attending the EGU 2014 Assembly?

The highlight of the Assembly is being able to meet other young researchers. You get very isolated as a PhD student. As an interdisciplinary student I often feel like strange, like I don’t belong to either research community my work sits within and that can lead me to think my problems are very much my own. The Assembly gives me the opportunity to meet and talk to people who are also doing interdisciplinary PhD. It’s nice to know there are people who are in the same boat as me.

Q8) If you could invent an element, what would it be called and what would it do?

Unobtanium – mineral that is in all the films. Solves the energy crisis and create clean fuel and clean itself up! It would probably glow as well.

Hazel undertook her undergraduate degree in physical geography with geology at Plymouth University. She then moved to Masters in hazard assessment, at Portsmouth University. Her first job was as an engineering geologist in Brisbane. The position gave her the opportunity to save lots of money, which allowed her to move onto a working as a volunteer in Mt St Helen’s as a ranger for a season. This role gave Hazel her first taste of public engagement and she enjoyed it so much she realised this was the career for her. After her time at Mt St. Helen’s she went onto the Natural History Museum in London and worked as a science educator and then moved onto a role as an Earth Science Identification Officer – identified what people sent in! She us now back at Plymouth University completing her PhD.

If you’d like to get in touch with Hazel you can reach her on email or twitter.

Moraines in Costa Rica? Really?

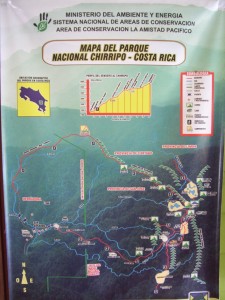

During a recent trip to Costa Rica in May, I had a conversation with some family and friends in which I uttered those words: “Moraines in Costa Rica? Really?” as they were describing a trek they’d undertaken earlier this year to the summit of Cerro Chirripó. This is the highest peak in the country (3819 m a.s.l.), part of the Cordillera de Talamanca (9°30′ N, 83°30′ W) in southern central Costa Rica.

Relief of Costa Rica and location of Cerro Chirripó. Base map courtesy of Sting (WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

While the photographs looked stunning (on a clear day, both oceans are visible from the summit), I was especially intrigued by their description of the landscape surrounding the peak: curved valleys, moraines and other landforms often associated with glacial activity were visible as they were above the tree-line. There are certainly no glaciers there at present (apparently hail occurs occasionally at the summit) and Costa Rica can definitely be classified as a tropical environment today. However this inspired me to track down research confirming (or not) that these landforms are indeed glacial in origin and, if so, discover the timing and duration of this period of high-altitude tropical glaciation.

It turns out the first papers on episodic glaciations in Costa Rica and other Central American countries emerged in the 1950s and investigations have continued through to the present day (particularly by researchers at the University of Tennessee). Much of the peer-reviewed research I found for Cerro Chirripó in particular is based on geomorphic surveys as well as analysis of sediment cores extracted from lakes located on valley floors along the flanks of the mountain. Many of these lakes have formed behind what appear to be moraines (see photo). A particularly interesting feature near the base of these sediment cores is a distinct shift from light-coloured material dominated by mineral particles to much darker brown or black sediments rich in organic matter. This transition is observed in lacustrine sequences all over the world, and certainly here in the UK, and is commonly attributed to the transition from the Younger Dryas interstadial at the end of the last glacial period into the early Holocene. The dark, more organic sediments are typical of deposition through the Holocene as the climate warmed and vegetation cover expanded around the world. A series of radiocarbon dates confirm a similar timing for these sediment transitions in multiple lakes around Cerro Chirripó, ranging between 12, 360 and 9, 470 calibrated years Before Present (BP) within the dating uncertainties (Horn, 1990; Orvis and Horn, 2000). The span of these dates likely relates to the relative position of the each lake with respect to the retreating glacier during the period of deglaciation, and the timing corresponds nicely with the Younger Dryas event (12, 900 – 11, 600 cal. yr BP). In fact, evidence for a Younger Dryas re-advance has been reported elsewhere in the neotropics including the Columbian Cordillera, the Eastern Cordillera of Equador, the Cordillera Real in Bolivia and around the Malinche volcano in central Mexico (references are found in Lachniet, 2004).

Panoramic view from summit of Cerro Chirripó with lakes visible in the foreground that have formed behind what appear to be moraines. Photo courtesy of Peter Anderson (WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

In terms of geomorphic evidence, phases of glacial advance and retreat are recorded by the large medial (a ridge running through the middle of a valley where two glaciers meet), lateral (two parallel ridges on either side of a glacier) and terminal (ridges formed at the end of a glacier) moraines found in the valleys around Cerro Chirripó. These fingerprints are found up to four hundred metres below the summit (Lachniet, 2004). Other field evidence includes striated bedrock (smoothed and grooved rock formed as ice moves across the surface; see photo).

To date, researchers have been unable to find suitable organic material at the base of the moraines to attempt radiocarbon dating but they are assumed to represent the maximum extent of the last ice advance, equating to a total ice-covered area of 35 km2. Similar features found at lower elevations in other parts of the Cordillera may point towards even more extensive ice cover during stages earlier in the Pleistocene but no effort to date these landforms has yet been invested. A recent review paper (Lachniet and Roy, 2011) emphasised that obtaining further radiocarbon dates from the lake sediments and landforms is critical to better understand the timing and duration of local and wider tropical glaciations. They also suggest OSL may be suitable, but cosmogenic radionuclide dating has been largely unsuccessful due to intense weathering of rock surfaces in the humid tropical environment.

Looking into the research and browsing through photographs of Cerro Chirripó has certainly inspired me to aim to hike up the mountain on my next visit to Costa Rica. One of the amazing things about Costa Rica and other Central American countries that I have backpacked through is how much the climate and landscape and culture can vary across relatively short distances – but trying to imagine glaciers sweeping down the valleys is very difficult to imagine!!

References

Horn, S.P. (1990) Timing of deglaciation in the Cordillera de Talamanca, Costa Rica. Climate Research 1, 81-83. PDF

Lachniet, M. (2004) Late Quaternary glaciation of Costa Rica and Guatemala, Central America. In: Ehlers, J., Gibbard, P. (Eds.) Quaternary Glaciations – Extent and Chronology Part III: South America, Asia, Africa, Australasia, Antarctica. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 135-138. DOI: 10.1016/S1571-0866(04)80118-0

Lachniet, M. and Roy, A. (2011) Costa Rica and Guatemala. In: Ehlers, J., Gibbard, P., Hughes, P. (Eds.) Quaternary Glaciations: Extent and Chronology. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 843-848. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53447-7.00060-X

Orvis, K. and Horn, S.P. (2000) Quaternary glaciers and climate on Cerro Chirripó, Costa Rica. Quaternary Research 54, 24-37. DOI: 10.1006/qres.2000.2142