Fridays are hard enough, so we thought we’d help you get through the day with a really interesting 10 minute interview, all you need now is a spare 10 minutes and your favourite hot drink!

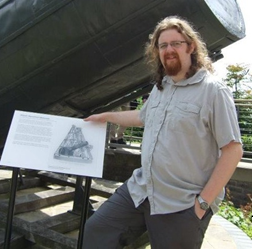

This week, we speak to Gillian McCay, assistant curator at the Cockburn Geological Museum at the University of Edinburgh. The museum is a fascinating place to visit, holding over 130,000 specimens as well as other materials. Gillian is proof that an Earth Science background can take you down many employment routes and she is definitely one of those unsung heroes of geology; keeping geological treasures safe and cataloged for future generations of Earth Scientists.

- You are: Gillian McCay (PhD) (I don’t call myself Dr… it sounds funny)

- You work at: School of GeoSciences, University of Edinburgh

- Your role is: Assistant Curator at Cockburn Geological Museum and Teaching Technician

Q1) What are you currently working on?

Several things! During term time I am always busy making sure that the labs and equipment are ready for practical classes – the summer is over and teaching has started! On the Museum side of things I am currently working towards an exhibition based on the theme of a Victorian Cabinet of Curiosities to be held in the University of Edinburgh’s Main Library. This space regularly has exhibits of around 20 – 50 objects… this exhibition will have close to 150 objects – the biggest display the University Collections have shown! – with around 40 specimens from the collection I care for.

Q2) What is a typical day like for you?

My day is really variable depending on the time of year. I ALWAYS start by turning on all the cabinet lights in the display cases and checking that nothing is amiss with the objects on show. During term time I then have a tour of the labs to make sure everything is in order there as far as equipment and specimens for teaching go – this can take anything from 10 mins to 40 mins depending on materials required for that day. After that, if everything is going to plan, I will try and get on with some museum projects such as cataloguing some of our collection (the catalogue of our historical collection currently only covers about 6000 of our 60,000 plus objects), doing environmental checks in our storage areas or doing some admin for our museum accreditation.

Q3) Does your job allow you to have any academic outputs?

My job doesn’t currently demand that I produce academic papers, but I am interested in developing the skills to publish in Curation Journals such as Geological Curator. I am currently getting a lot of Charles Lyell’s personal papers digitised and hope that these could be the basis of a really interesting project.

Q4) What has been the highlight of your career so far? As an early stage researcher where do you see yourself in a few years time?

I have had a few amazing things happen since I started my job last year. I held a small object handling session for a delegation from the European Space Agency, which was great fun. I have also had the shock of finding specimens collected by Charles Darwin during his time on the Beagle that had gotten ‘lost’ in the collection here! As a permanent member of staff I could still be here 10 years from now and although moving to a bigger collection would be interesting I feel quiet attached to the objects I care for in the Cockburn Museum.

Q5) To what locations has your research taken you and why?

Currently my Job mostly takes me to Museum Store Rooms, so it’s not that exotic… but some of the things you get to see are amazing!!!

Q6) Do you have one piece of advice for anyone wanting to have a career similar to yours?

Get hands on experience… I was lucky and fell into museum/collection work, but if you want to get into it, it’s mega competitive. Some people volunteer for years before finding a paid position so it’s a massive bonus if you can start early and get involved with university collections during your degree.

Q7) If you could invent an element, what would it be called and what would it do?

Time-travellum (Tt) – it would power the time machine I would build so I could go back and see amazing geological events.

Gillian is originally from Northern Ireland but moved to Scotland as a fresh faced undergrad studying geoscience in St Andrews and later moving to Edinburgh to do a PhD. Although she still thinks of herself as a Field Geologist, these days she mostly chases “free living” rock specimens round the School of GeoSciences Grant Institute making sure they get back to their homes in the cabinets. Gillian enjoys visitors and encourages curious artists and members of the public to come and visit the rocks she cares for.