During a recent trip to Costa Rica in May, I had a conversation with some family and friends in which I uttered those words: “Moraines in Costa Rica? Really?” as they were describing a trek they’d undertaken earlier this year to the summit of Cerro Chirripó. This is the highest peak in the country (3819 m a.s.l.), part of the Cordillera de Talamanca (9°30′ N, 83°30′ W) in southern central Costa Rica.

Relief of Costa Rica and location of Cerro Chirripó. Base map courtesy of Sting (WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

While the photographs looked stunning (on a clear day, both oceans are visible from the summit), I was especially intrigued by their description of the landscape surrounding the peak: curved valleys, moraines and other landforms often associated with glacial activity were visible as they were above the tree-line. There are certainly no glaciers there at present (apparently hail occurs occasionally at the summit) and Costa Rica can definitely be classified as a tropical environment today. However this inspired me to track down research confirming (or not) that these landforms are indeed glacial in origin and, if so, discover the timing and duration of this period of high-altitude tropical glaciation.

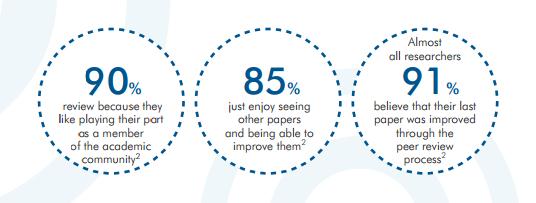

It turns out the first papers on episodic glaciations in Costa Rica and other Central American countries emerged in the 1950s and investigations have continued through to the present day (particularly by researchers at the University of Tennessee). Much of the peer-reviewed research I found for Cerro Chirripó in particular is based on geomorphic surveys as well as analysis of sediment cores extracted from lakes located on valley floors along the flanks of the mountain. Many of these lakes have formed behind what appear to be moraines (see photo). A particularly interesting feature near the base of these sediment cores is a distinct shift from light-coloured material dominated by mineral particles to much darker brown or black sediments rich in organic matter. This transition is observed in lacustrine sequences all over the world, and certainly here in the UK, and is commonly attributed to the transition from the Younger Dryas interstadial at the end of the last glacial period into the early Holocene. The dark, more organic sediments are typical of deposition through the Holocene as the climate warmed and vegetation cover expanded around the world. A series of radiocarbon dates confirm a similar timing for these sediment transitions in multiple lakes around Cerro Chirripó, ranging between 12, 360 and 9, 470 calibrated years Before Present (BP) within the dating uncertainties (Horn, 1990; Orvis and Horn, 2000). The span of these dates likely relates to the relative position of the each lake with respect to the retreating glacier during the period of deglaciation, and the timing corresponds nicely with the Younger Dryas event (12, 900 – 11, 600 cal. yr BP). In fact, evidence for a Younger Dryas re-advance has been reported elsewhere in the neotropics including the Columbian Cordillera, the Eastern Cordillera of Equador, the Cordillera Real in Bolivia and around the Malinche volcano in central Mexico (references are found in Lachniet, 2004).

Panoramic view from summit of Cerro Chirripó with lakes visible in the foreground that have formed behind what appear to be moraines. Photo courtesy of Peter Anderson (WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

In terms of geomorphic evidence, phases of glacial advance and retreat are recorded by the large medial (a ridge running through the middle of a valley where two glaciers meet), lateral (two parallel ridges on either side of a glacier) and terminal (ridges formed at the end of a glacier) moraines found in the valleys around Cerro Chirripó. These fingerprints are found up to four hundred metres below the summit (Lachniet, 2004). Other field evidence includes striated bedrock (smoothed and grooved rock formed as ice moves across the surface; see photo).

To date, researchers have been unable to find suitable organic material at the base of the moraines to attempt radiocarbon dating but they are assumed to represent the maximum extent of the last ice advance, equating to a total ice-covered area of 35 km2. Similar features found at lower elevations in other parts of the Cordillera may point towards even more extensive ice cover during stages earlier in the Pleistocene but no effort to date these landforms has yet been invested. A recent review paper (Lachniet and Roy, 2011) emphasised that obtaining further radiocarbon dates from the lake sediments and landforms is critical to better understand the timing and duration of local and wider tropical glaciations. They also suggest OSL may be suitable, but cosmogenic radionuclide dating has been largely unsuccessful due to intense weathering of rock surfaces in the humid tropical environment.

Looking into the research and browsing through photographs of Cerro Chirripó has certainly inspired me to aim to hike up the mountain on my next visit to Costa Rica. One of the amazing things about Costa Rica and other Central American countries that I have backpacked through is how much the climate and landscape and culture can vary across relatively short distances – but trying to imagine glaciers sweeping down the valleys is very difficult to imagine!!

References

Horn, S.P. (1990) Timing of deglaciation in the Cordillera de Talamanca, Costa Rica. Climate Research 1, 81-83. PDF

Lachniet, M. (2004) Late Quaternary glaciation of Costa Rica and Guatemala, Central America. In: Ehlers, J., Gibbard, P. (Eds.) Quaternary Glaciations – Extent and Chronology Part III: South America, Asia, Africa, Australasia, Antarctica. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 135-138. DOI: 10.1016/S1571-0866(04)80118-0

Lachniet, M. and Roy, A. (2011) Costa Rica and Guatemala. In: Ehlers, J., Gibbard, P., Hughes, P. (Eds.) Quaternary Glaciations: Extent and Chronology. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 843-848. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53447-7.00060-X

Orvis, K. and Horn, S.P. (2000) Quaternary glaciers and climate on Cerro Chirripó, Costa Rica. Quaternary Research 54, 24-37. DOI: 10.1006/qres.2000.2142