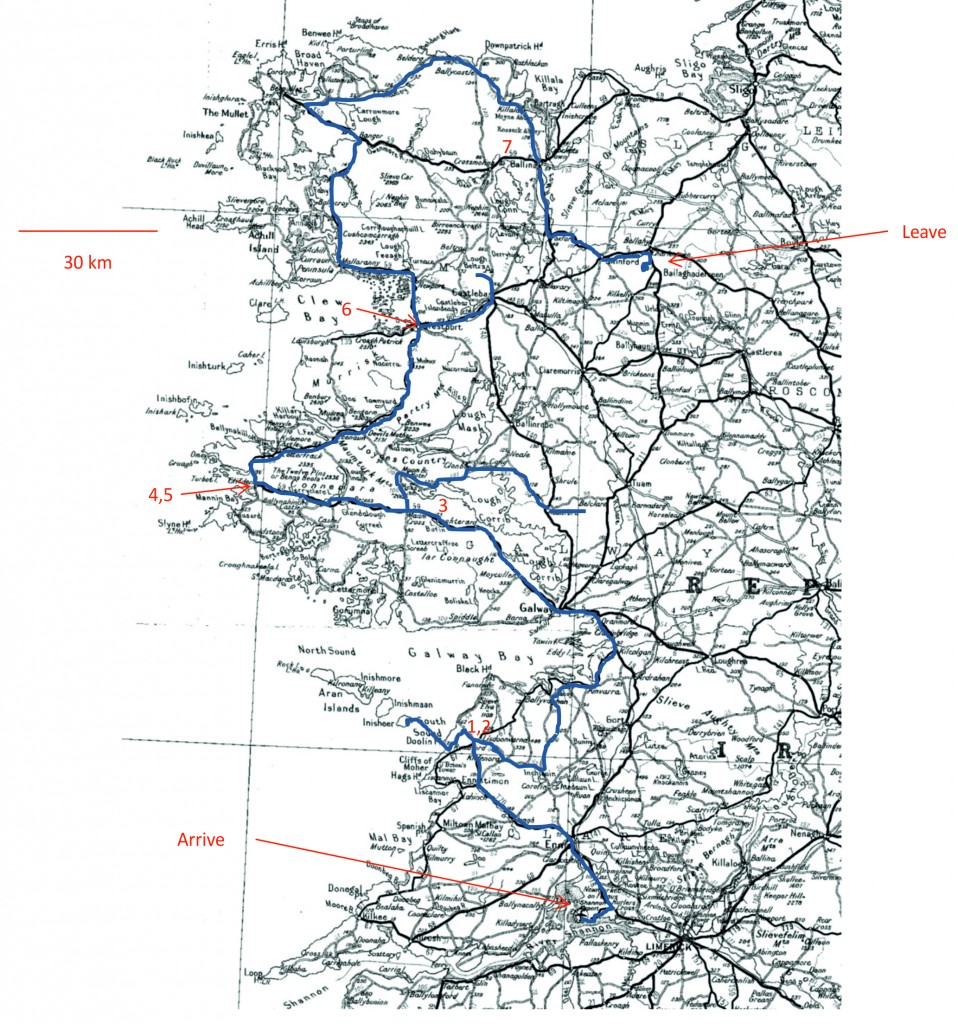

The four-year DYNAMITE project (DYNAmic Models in Terrestrial Ecosystems and Landscapes), a teaching and research cooperation programme between the School of Environmental Sciences, University of Liverpool, UK and the Departments of Geology and Physical Geography and Ecosystem Science at Lund University, Sweden, recently ended with an excursion for PhD students, postdocs and academic staff from both institutions to western Ireland in September 2013.

A brief report from the trip offers an excellent overview of the breadth of Quaternary Science as a discipline, illustrating how we integrate geomorphology, archaeology, geology and palaeoecology, to foster better understanding of local- to global-scale environmental change at varying temporal scales through the Holocene and Pleistocene.

Archaeology

Our trip began (Day 1) in The Burren, an extensive karstic landscape composed of remarkable limestone pavements and that supports many rare species.

Michael Gibbons talking about Oyster harvesting, meal preparation and shell waste deposition and modern day exposure of a Neolithic Oyster Midden. Photo: D. Schillereff

Michael Gibbons guided us around a number of fascinating archaeological sites, many of which feature in this detailed report from the Burren Landscale and Settlement Project. We visited impressive hill forts, court tombs and exposed oyster middens, many of them dating from Neolithic, and in some cases Mesolithic, age.

Many sites in the Burren have yet to be excavated, including these stone piles in the tidal zone; what was their purpose and when were they constructed remains to be discovered.

The trip also ended (Day 6) discussing archaeology, specifically the Céide Fields Neolithic complex at Ballycastle, County Mayo. These field systems enclosed by stone walls represent the most extensive Neolithic Stone Age monument in the world, dating to 5000 – 6000 years ago, and is today mostly covered by extensive blanket peat except for a few isolated areas currently undergoing excavation. The age of the walls is determined by applying radiocarbon dating to fossilized pine stumps preserved in the bog. Seamus Caulfield (Archaeology, University College Dublin) who has focused much of his research career on these sites led an extensive guided tour of the excavations, where the peat has been removed at various intervals revealing the abandoned stone walls.

Professor Seamus Caulfield describing an excavated stone wall section in the Céide Fields. Photo: D. Schillereff

While individually the piles of stone do not initially appear tremendously impressive, when the spatial extent (>10 km2) and perfectly parallel construction of the walls is considered, the enormous scale of Neolithic agriculture in the region is unveiled. What is also of great interest is the rarity or lack of preservation of a monument of similar age elsewhere in northwest Europe. It appears most likely that a regional decline in pine forests (indicated by pollen reconstructions) meant stone walls were constructed at great effort, instead of the log walls constructed from forest timber at the time elsewhere in Europe.

Palaeoecology

A short boat ride on Day 2 took us to Inis Oírr, the smallest of the Aran Islands, led by Karen Molloy (National University of Ireland, Galway). The small field boundaries struck me as unusual but apparently such land division has a long history in western Ireland (as we discovered at the Céide Fields). Karen presented the impressive lake sediment sequence of An Loch Mór; the unique setting of the lake means the >13 m of sediment deposited here records a fascinating story of palaeoecological change (e.g., Holmes et al. 2007, QSR) through the late-Glacial and Holocene periods, including insight into local ice retreat at the end of the last glaciation, sea-level and salinity changes, vegetation history and phases of exceptionally high windspeed due to its exposure to the Atlantic Ocean.

Later in the trip (Day 4) we tracked down a small exposed organic deposit exposed in a fluvial terrace at Derrynadivva that contained many large plant macrofossils. It turns out these deposits are not Holocene in age; rather, they are remnants of plants growing during a previous Pleistocene interglacial. It remains uncertain which interglacial is represented here however based on analysis of the pollen and plant macrofossils, the deposit possibly represents Oxygen Isotope Stage 11 (Hoxnian; e.g., Coxon et al. 1994 JQS).

Interglacial deposit containing many large plant macrofossils exposed in an alluvial terrace. Photo: D. Schillereff

Glacial Geology and Geomorphology

We visited a number of sites around Co. Galway, Co. Mayo and Connemara (Days 3 – 5) with Professor Peter Coxon (Geography, Trinity College Dublin) and Dr Richard Chiverrell (Environmental Sciences, University of Liverpool) to examine the complex, fascinating and still-unresolved history of Late Glacial ice-retreat in western Connemara. The stunning landscape of Connemara bears vast evidence of ice-sculpting during the last glacial period, including the elongated fjord of Killary Harbour, the Twelve Bens mountain massif that rises almost directly from the sea and the partly submerged drumlin field at Clew Bay.

View over the drowned drumlin field in Clew Bay. Photo by K. Campbell, Geograph.org, from WikiCommons

This exposed drumlin was particularly impressive as it is a rare example of coastal erosion revealing a length-wise cross-section through the middle of a drumlin. One can thus walk along the beach examining its internal sedimentology in great detail. The sharp contact to angular facies at the head of the drumlin, suggesting coarse sediments rapidly deposited by sub-glacial meltwater in a cavern beneath the ice, was especially neat.

Angular facies at drumlin head related to deposition of coarse sediment from sub-glacial meltwater stream. Photo: D. Schillereff

We visited quarries at Tullywee cut into a subacqueous fan series related to ice retreat (~20 – 18 k years ago) that imply a water-surface of 60-65 m above IOD and the large ice-contact delta at Leenaun at the end of Killary Harbour that exhibits a classic Gilbert-style structure and also implies a high shore-level of 78 m IOD. The causal mechanism(s) for this high sea-level stand have yet to be fully deciphered, especially the question of whether the water at these ice-contact features was glacio-marine (much higher local sea-level than models or other reconstructions possibly suggest) or glacio-lacustrine (enormous ponds dammed by ice further seawards, requiring immensely complex ice-streaming configuration). More discussion of these implications can be found in Thomas & Chiverrell, 2005 QSR.

Many pristine examples of glacial geomorphology were observed during the trip, for example the eskers at Tullywee, as well as much smaller features such as this ‘dropstone’ in a small exposure in the Leenaun delta. One could easily stroll past and not realise the significance of this cobble; the deformed sediments indicate we were adjacent to a calving margin and this cobble exited the iceberg as it floated seawards and was deposited in the soft sediments below.

It was a wonderful trip, tremendously educational and certainly a place I’d love to visit again for its visual beauty and ideally for the purpose of research as there is much yet to be understood about the Quaternary environments of western Ireland.

For interested readers, the Quaternary of Central Western Ireland (edited by Professor Pete Coxon, 2005) contains a wealth of further information on many of these sites and other case studies.