I am sitting in a hot lecture theatre in the Università deli Studi, Florence, two days before the start of the proper business of Goldschmidt 2013, a meeting of thousands of geochemists from across the globe. Before discussions of the latest news and views in the geochemical world, a number of pre-conference workshops and short courses are taking place. It’s a chance to get an introduction and overview of the problems and methods in a particular domain.

I am sitting in a hot lecture theatre in the Università deli Studi, Florence, two days before the start of the proper business of Goldschmidt 2013, a meeting of thousands of geochemists from across the globe. Before discussions of the latest news and views in the geochemical world, a number of pre-conference workshops and short courses are taking place. It’s a chance to get an introduction and overview of the problems and methods in a particular domain.

The thermodynamic properties of geothermal fluids control how chemical elements are transported and concentrated, relevant to formation of metal ores, how chalky precipitates form in your kettle or central heating system, how energy can be extracted in engineered geothermal plants, how fluids flow from subducted crust to volcanoes in subduction zones, how CO2 might behave as it is pumped into carbon capture and storage sequestration sites, and even how organisms can survive and flourish in crustal rocks.

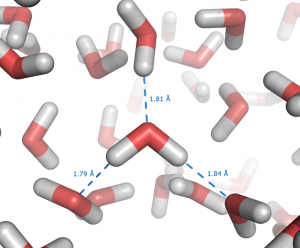

The starting point for much of our understanding lies in how water molecules respond to temperature, to pressure, and to changes in their chemical environment as salts are added to watery fluids. Fundamentally, it all depends on how the atoms interact in the fluid.

There are certain inherent problems of describing atomic interactions at the molecular scale. One is linked to the “three-body problem”. The properties of a geofluid or mineral can be calculated by considering interactions between all the atoms present. But those interactions can only be calculated between pairs of atoms. In practise, interactions between more than two atoms are approximated as being due to pairs, and the pairwise interactions are then summed up.

It is rather like trying to calculate the movements of the Earth, Moon and Sun with respect to each other. There are three astronomic bodies present, but the movements of the spheres are treated as the sum of the Earth-Moon, Moon-Sun, and Earth-Sun interactions. Geomaterials are treated in the same way, at a far smaller scale.

While reflecting on this, I was reminded of the earlier notable work on those larger-scale interactions, carried out in this city, that transformed our view of Earth.

While reflecting on this, I was reminded of the earlier notable work on those larger-scale interactions, carried out in this city, that transformed our view of Earth.

On my way to the lecture theatre this-morning I had stopped off at Basilica di Santa Croce. It is the last resting place of Galileo, and I took a look at his tomb. It is a wonderful monument. It is interesting to see how it contrasts with some of the others around him in the church (including Machiavelli, Rossini and memorials to Dante, Marconi and Enrico Fermi).

Striking features include the depiction of Galileo holding a telescope and globe, rather in the style of the orb and sceptre of a King or Emperor. Figures to his side hold geometric charts. A golden Sun is shown with circling planets. And above his head is a ladder (pointing to heaven?!) – his family symbol.

Galileo realised, from the movements of the tides, that the moon circled Earth and Earth orbits Sun. His views, famously, put him on a collision course with the Church’s then view of the Universe. The rest of this week is rather likely to be somewhat geo(chemically)-centric, but not, I think, in a sense that would cause Galileo any grief.