As part of the ‘What’s geology got to do with it?’ series, Flo takes us on a tour of the links between geology and tennis! Warning: You may not want to read this if you have no interest in Geology OR tennis….

Now the disclaimer’s out of the way, I thought it was about time I married two of my greatest loves in life, Geology and Tennis. These two interests may seem completely at odds in terms of relevance, but as is the beauty with geology, it relates to just about everything!

So, summer in the northern hemisphere and therefore the two biggest Grand Slams in tennis are upon us! The French Open, the king of the clay-court season is currently underway and Wimbledon, the jewel (and one of the few remaning…) grass court tennis tournaments is just around the corner.

But for a sport containing so few tangible objects: a court, a racket, a person and a tennis ball, how does it relate to Geology? Well….

Tennis Courts

Court Philippe Chatrier Court at the French Open, the only Grand Slam played on red clay. Source – Wikimedia Commons

Professional tennis is played on 3 types of court surface, each with its own season during the tennis calendar. You have the hard court season, which dominates most of the year between July and February, beloved by Djokovic, then you have the European and North and South American clay court season from February to May, favourite of clay-court extroadinaire Rafa Nadal and then the shortest season of all, the grass court season, occupying all of 4 weeks in the summer, from June-July, once dominated by Federer and recently by Murray! The most obvious link to geology here is the clay courts, so how do you go about building a clay court and what materials do you need?

Red Clay Courts

Well first of all, very few clay courts are actually made of natural clay. This is because they can take a very long time to dry out (which you’ll know if you’ve ever done any pottery….). For this reason, the red clay courts as seen at the French Open and numerous other clay court tournaments are actually made from crushed brick or shale. Bricks are used because they absorb water less easily than natural clay and are produced from a mix made from Alumina (clay), sand, lime and iron oxide before being fired until dry.

Guga Kuerten being awarded a cross-section of the court in his last match at the French Open in 2008. Source – Tennis Served Fresh Blog

So if you want to build a clay court like the famous red-clay courts of the French Open, first of all you need to lay a base layer, this is covered with a layer of crushed stones, this is then overlain by a layer of clinker. This is then followed by a layer of crushed limestone and finally, the crushed brick forms the thinnest layer at the top. A cross section of the layering under the court surface formed the trophy that former French Open champion Guga Kuerten received when he played his last match at the tournament in 2008!

You wouldn’t want the Philippe Chatrier court looking like this after a few hours of sunshine! Source – Wikimedia Commons.

Maintenance of the court after completion is a bit tricky as the clay needs to be constantly smoothed and watered in order to prevent dewatering cracks, a feature that many geologists are very familiar with!

Green Clay Courts

Maria Sharapova playing on the ‘green clay’ at the Family Circle Cup. Source – Wikimedia Commons

Not all tournaments use red clay, so called ‘green’ clay’ or ‘Har-Tru’ has become very popular in the United States. Har-Tru courts are similar in construction but are made from crushed basalt rather than brick meaning they are slightly harder and faster. According to their website, Har-Tru courts are made from ‘billion-year old Pre-Cambrian metabasalt found in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia‘. This rock has two important properties, which is that it is hard and angular which allows it to ‘lock together to form a stable playing surface’ and the hardness provides ‘exceptional durability’.

Tennis rackets

A modern tennis racket with a carbon fiber-reinforced polymer frame. Source – Wikipedia Commons

As with many manufactured items, the raw materials required to make them eventually leads us back to our natural resources in the ground. Earlier tennis rackets were always made from wood, with strings made from gut, but these days, advancements in materials technology means that the majority of professional frames are made from ‘high modulus graphite and/or carbon fibre while titanium and tungsten are often added to give the frame more stiffness and the strings are made from nylon (although Federer and Sampras are famous for using natural gut strings).

Supplies of pure titanium are rare although titanium ores such as ilmenite and rutile are much more common. Titanium is largely mined in the titanium-rich sands of Florida and Virginia as well as Russia, Japan, Kazakhstan and other nations. Much more rare is Tungsten, which has seen a rapid rise in price in recent years as supplies dwindle. Tungsten has recently emerged as a ‘critical’ metal with the majority of the world’s tungsten supply located in China. However Hemerdon mine in Devon which has been closed since 1944, is thought to host one of the largest tungsten and tin deposits in the world, and is set to reopen under control of an Australian firm in the near future with permit plans progressing this year.

For more on how a tennis racket is made: http://www.madehow.com/Volume-3/Tennis-Racket.html

Tennis Balls

Tennis ball advertisment, 19th century. Source – Wikimedia Commons

According to an article in the guardian published in 2013, manufacture of Slazenger tennis balls now has a 50,000 mile production journey before they end up in Centre Court at Wimbledon. Part of this journey includes the transport of various mineral resources. These include the transport of clay from the United States, Petroleum Napthalene (derived from coal tar) from China, Sulphur from South Korea, Magnesium Carbonate from Japan, Silica from Greece and Zinc Oxide from Thailand. This exemplifies not just the truly global nature of the manufacturing markets but also the complex importing and exporting of many natural resources for something as simple as a tennis ball.

For more on how tennis balls are made, see the ITF website: http://www.itftennis.com/technical/balls/other/manufacture.aspx

Tennis Net

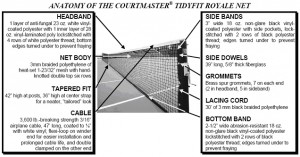

Anatomy of a tennis net. Source – Do it tennis website.

The majority of the different parts of a tennis net are made up from either polyester or polyethylene, both formed synthetically. However, the raw materials required to synthesise both materials started off as extracted hydrocarbons. Polyester synthesis requires the polymerisation of ethylene which is derived from petroleum.

60 million tonnes of polyethylene is manufactured each year and is the world’s most important plastic. It is made by several methods by addition polymerisation of ethene, which is principally produced by the cracking of ethane and propane, naptha and gas oil, all hydrocarbon fractions. In Brazil, a plant is being constructed to make polyethylene from sugar cane via bioethanol.

And that’s how geology underpins everything we know and love about tennis!

For more information on the link between sports and geology, see the United States Geological Survey’s article on ‘Minerals in Sports: Tennis’: http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/general_interest/sport_mins/tennis.pdf