Whether in a concerned, neutral, alarmist or sceptical tone, climate change is often reported in the media. But has the press approached this subject differently over the years? Marion Ferrat takes a look at the UK press coverage of the last two IPCC reports and investigates how the treatment of climate change has changed in British newspapers.

Glaciers outside of Ammassalik in Greenland – Source: Christine Zenino, Wikimedia Commons.

Last week, polling expert Leo Barasi posted the results of a very interesting study in his public opinion blog Noise of the Crowd. Following the waves of flooding that have hit the UK – and been at the centre of the UK press coverage – for the past month, he analysed the trends in flooding stories in the newspapers since 2005. He found that the number of news articles about flooding that also mentioned climate change dropped from 25% in 2009 to 11% last year.

This result reflects a broader trend in the public perception of climate change. Since the 2009 Copenhagen climate change conference, there has been a decrease in the number of people believing in human impacts on climate, and a rise in climate change scepticism.

One of the triggers of this change was the unfortunate email hacking incident at the University of East Anglia, commonly referred to as Climategate. In November 2009, over 1000 private emails between scientists of the Climatic Research Unit were stolen and released online. Some of these emails were interpreted as scientists hiding data in a bid to convince the world of the dangers of global warming. The controversy took the internet by storm and, although a careful investigation later showed that the scientists had not behaved in an untrustworthy way or manipulated any data, the damage was done.

The London Times, 6 July 1863 – Source: Wikimedia Commons.

After the release of the last IPCC report in September 2013, I carried out a similar analysis of climate change coverage in the UK press. I compared the press coverage of this fifth Assessment Report (AR 5) with that of the previous report (AR 4) in February 2007. Using a newspaper database called Factiva, I read all the news articles published in eight UK daily newspapers during the week of the two reports’ release1. Here is what I found.

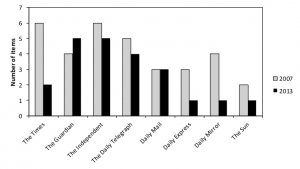

News coverage of IPCC AR 4 and AR 5

The 5th Assessment Report (2013) saw less coverage than the 4th Assessment Report (2007), with 22 and 33 articles, respectively. The majority were published in The Times, The Guardian, The Independent and The Daily Telegraph. Over 80% of the news stories were covered by specialist science or environmental correspondents in 2013, against 48% in 2007.

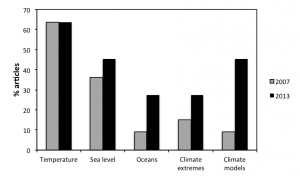

What type of climate change?

I was interested in what was actually being reported in the press. Were journalists more concerned by air temperatures or ocean warming, or perhaps extreme events?

In 2007 and 2013, all newspapers talked about changes in temperature (64% in both years). Discussions of changes in sea level increased from 36% to 45% in 2007 and 2013, respectively, and climate extremes from 15 to 27%.

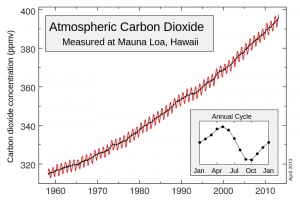

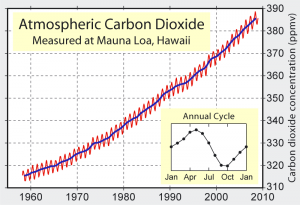

Coverage mentioning the oceans trebled from 9% in 2007 to 27% in 2013. This is interesting given the controversy surrounding the so-called “warming hiatus”. Global atmospheric temperatures have been relatively stable since 1998, and climate sceptics argue this is evidence that CO2 emissions do not dangerously affect temperatures. Scientists have suggested that the oceans have a complex role to play in modulating atmospheric temperatures.

But the most obvious change was the number of articles mentioning climate models. Despite being a central component of scientific results in both reports, references to models in the press were made in only 9% of the 2007 articles against 45% in 2013.

From scared to sceptical: a changing tone

In 2007, 42% of the articles across all news outlets but The Daily Mirror described the report as bleak, sobering, gloomy, frightening, grim, stark or terrifying. These adjectives were absent from the 2013 coverage, which rather used more neutral words such as most comprehensive, most authoritative or making the most overwhelming case (27% of the articles).

One big difference was the number of direct references to climate change scepticism or denial, which doubled from 30% in 2007 to 59% in 2013.

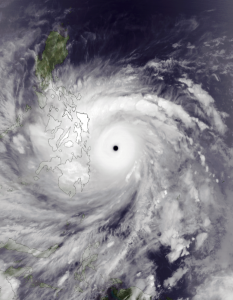

From cataclysm to careful concern in Britain

Newspapers such as The Daily Express, Daily Mail and The Sun were most concerned with consequences of climate change in Britain. Interestingly, these concerns were different in 2007 and 2013. The references were very sensationalist in 2007, with reports in The Daily Express, The Daily Mirror and The Sun that climate change “would devastate Britain”, which would face “disasters similar to the devastation […] caused by Hurricane Katrina”. They were more moderate in 2013, referring only to Britain likely experiencing “wetter winters and drier summers”.

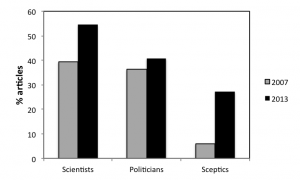

Says who?

Quotes are an important part of a news article. They give weight to particular aspects of a story and enable journalists to convey opinions whilst maintaining the objectivity of their reporting.

In 2007, 39% of all articles contained quotes from scientists, rising to 55% in 2013. The percentage of articles containing quotes from politicians also rose from 36% to 41%. Most quoted politicians in each case were the Environment Secretary David Miliband (2007) and the Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change Ed Davey (2013), both stressing the importance of climate change mitigation.

The largest change can be seen in the percentage of articles including quotes from climate change sceptics, which increased from 6% in 2007 to 27% in 2013.

What has changed?

Overall, the coverage of both IPCC reports was factual, detailed and accurate across all newspapers studied. The 5th Assessment Report saw less coverage than AR 4, suggesting a general dip in public interest in climate change. One interesting point was the discrepancy between the articles’ content and their titles in tabloid papers. Although the articles themselves were generally quite neutral, their titles voiced a much more pronounced scepticism. Given that most people would first and foremost read and remember an article’s title, their wording can have an important impact on public opinion.

The tone of the 2013 coverage was both less sensationalist (e.g. minimal use of words such as stark and terrifying) and more likely to include mentions of- and quotes by climate change sceptics.

In terms of scientific content, the main difference was the inclusion of the concept of climate models and their limitations and strengths in the 2013 press coverage (in 45% of articles against only 9% in 2007). This is possibly also in response to the ‘warming hiatus’, rather than because climate models have been a larger part of AR 5.

The political nature of the climate change debate was seen in the coverage of both IPCC reports, with over one third of the articles quoting politicians in both years.

The biggest difference was the much larger place given to climate change sceptics in the news coverage, nearly doubling from 30% in 2007 to 59% in 2013. Despite the increased certainty of the IPCC results from AR 4 to AR 5 (moving from 90% to 95% certainty that humans are influencing climate), it is clear that there is more room in the media today for uncertainty and climate change scepticism.

Marion

1This study covered the release of the Working Group 1 reports. News articles were selected from the News sections only, by searching for the terms climate change and either IPCC or Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.