Flo summarises 5 geo-relevant policy issues that are likely to impact on the Scottish Independence Referendum.

Sooooo apologies for the long blog holiday we’ve been on of late, Marion and I have had a fairly hectic summer, but fear not, we will be updating on a more regular basis from now on!

Source – Wikimedia Commons, Credit: Smooth_O.

Hitting the headlines in the UK this week is the impending referendum for Scottish Independence taking place on the 18th September. Latest polling suggests that the vote outcome is on a knife-edge. Either way, the build-up and inevitable political wrangling after the result undoubtedly means that the situation has changed for everyone, regardless of the outcome. One thing is for sure: the implications of an independent Scotland means big changes for both countries, the shape of which is still little understood and requires much discussion in the negotiation stages.

Taking a sidestep from the core politics for the moment, I’m going to have a brief look at 5 geology related topics in the run up to the referendum that could be affected, for better or worse depending on your point of view, by the decisions made next week!

This topic, like others with a geopolitical element, tells another interesting story about the link between the fortuitous geo-location of resources and the creation of nation states.

Fossil Fuel Reserves: The North Sea and Shale Gas

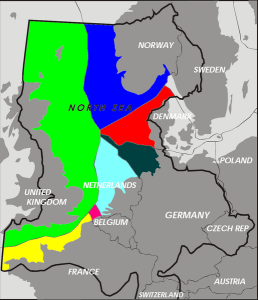

Exclusive economic zones for the North Sea, the green refers to the area covered by the UK Continental Shelf. Source – Wikimedia Commons, Credit: Inwind.

North Sea oil and gas has formed a significant proportion of revenue for the UK since the mid 60’s when the UK Continental Shelf Act came into force. Since then the UK government, via the UK continental shelf economic region, has controlled licensing of hydrocarbon extraction. This has been a particularly crucial source of revenue for the UK which peaked in 1999 with production of 950,000m3 (6 million barrels a day). In an independent Scotland, income from the remaining hydrocarbons in the North Sea would provide a considerable amount of revenue, but the rights over the North Sea, in the event of an independent Scotland are unclear, as it is yet to be negotiated. The majority of the confusion over this issue arises from the line in the North Sea that would demarcate Scottish territory. Many agree that this is likely to be drawn along the ‘median line’ or ‘equidistance principle’: a ‘line between the nearest points of land on either side using the baselines established around the coast of the UK in accordance with international law’ (from the UK Government’s Scotland Analysis: Borders and Citizenship). On this basis, Scotland’s share of the North Sea would be somewhere between 73-95% according to different sources. Further complications lie in the debate over the estimates of reserve remaining and whether it is more difficult to extract (geologists will be more than familiar with this sort of uncertainty!!).

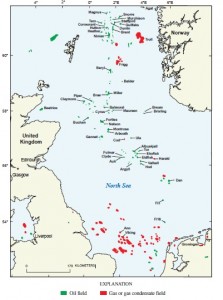

North Sea oil and gas fields distribution. Source – Wikimedia Commons, Credit: Gautier, D.L .

A fact check produced by Channel 4 earlier this year cast doubt on the values of remaining reserves. These unknowns have made confident and informed arguments on this topic difficult for both sides. This may not be critical, however, as leaving the North Sea out of the Scottish economy completely, it is still a thriving economy: only slightly smaller than that of the UK.

Another issue that has been discussed in the run up to the Scottish independence referendum is Scotland’s shale gas reserves and the issue of fracking. A report published just last week by the N56 business body claimed that fracking of what would be Scotland’s oil and gas reserves could almost double the amount recoverable from oil and gas in the North Sea, the target being the Kimmeridge Bay formation, an Upper Jurassic organic rich shale which is the major oil and gas source rock for the Central and Northern North Sea. The BGS has since debunked this estimate stating that there is only “a modest amount” of shale gas and oil reserves.

There is a more detailed discussion of these issues on Carbon Brief’s blog

Climate Change and Renewable Energy

Wether Hill, Dumfries and Galloway wind farm. Source – Wikimedia Commons, Credit: Walter Baxter.

Scotland has some pretty impressive environmental credentials when it comes to renewable energy, a staggering 69% of Scotland’s electricity was generated from a combination of renewables (29.8%) and nuclear (34.4%) in 2012. Scotland has a massive renewable resource and the Scottish National Party (SNP) have been vocal in stating that they want to make Scotland the green capital of Europe. The Yes campaign website states that ‘Scotland is on target to meet all of its electricity needs, and 11% of its heat requirements, from renewable sources such as wind, wave, tidal, solar and biomass by 2020′. As it stands, control over energy policy and funding resides with Westminster. The Scottish Government has shown a commitment to low-carbon energy sources in its 2009 paper which introduced ambitious plans to reduce emissions by at least 80% by 2050.

Carbon Capture and Storage

Peterhead Power Station, Site of DECC CCS funding. Source – Wikimedia Commons, Credit: PortHenry.

After some very slow progress in the DECC CCS competition (see my earlier post on this), the shortlist (not even the final selection) was eventually announced last year with two shortlisted sites, one of which is the Peterhead Project off the coast of Aberdeenshire, which has been awarded a funded contract to undertake front-end engineering and design studies. The Peterhead Project may well have an uncertain future if the referendum turns out a ‘Yes’ result. Energy Secretary Ed Davey admitted that the progress of the Peterhead CCS plant would be significantly trickier in the event of independence. While the Yes campaign has outlined its low-carbon credentials, a future Independent Scotland may find it hard to justify funding the very expensive CCS scheme alone. We could, however, end up in a situation where rUK (rest of the UK – the successor state in the event of Scottish independence) projects send their CO2 to storage sites in the North Sea, the revenues of which would go to an independent Scotland. This would mean that Scotland could still benefit from CCS development even if development at Peterhead is cancelled.

Research and Science Funding

Grant Institute, School of Geosciences, Edinburgh University. Source – Wikimedia Commons, Credit: Kay Williams.

Much has been written about the future of science research and funding in the event of a Yes vote at the referendum. Some groups of scientists have come out to say that a Yes for independence could damage the country’s research base and hurt the economy, this was stated most recently by the presidents of the Royal Society, the British Academy and the Academy of Medical Sciences. In contrast, the ‘Academics for Yes‘ group states that Scottish independence will secure and enhance the international profile of Scottish universities and also boost work between the research sector and the government to develop Scotland’s economy, as well as giving them control of research priorities. A piece posted just this week in Nature showed that opinion is split with regards to the impact of independence on science research and funding, with some touting improved innovation under independence and others saying that the border would hinder the open exchanges under which science thrives.

Radioactive Waste Disposal

Dounreay nuclear power development, Caithness. Source – Wikimedia Commons, Credit: Ben Brooksbank.

The Scottish Government’s energy policies, in contrast to Westminster, favour renewable energy as well as use of North Sea Oil and Gas over what is described as ‘risky’ nuclear power and their policies for radioactive waste disposal also differ from that of Westminster. While Scotland has stated that it won’t be developing new-nuclear power it has an extensive history of nuclear power generation which has its own legacy waste associated with it. The Scottish Government, unlike the UK Government, has stated it will not use geological disposal as a method of waste storage and their policy is that waste should be stored in near-surface facilities and recognises that ‘long-term management options may not be feasible at present or have yet to be developed‘. A recent academic paper on this issue suggested the following:

Additional confusion with regards to radioactive waste policy arises from the difference between ‘spent fuel’ and waste. Spent fuel is defined by the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission as:

the bundles of uranium pellets encased in metal rods that have been used to power a nuclear reactor. Nuclear fuel loses efficiency over time and periodically, about 1/3 of the fuel assemblies in a reactor must be replaced. The nuclear reaction is stopped before the spent fuel is removed. But spent fuel still produces a lot of radiation and heat that must be managed to protect workers, the environment and the public.

Spent fuel is not currently classified as waste, and therefore can be traded and sent overseas for processing, whereas this is banned for material classified as ‘waste’. Currently, the Thorp Reprocessing plant at Sellafield accepts spent fuel contracts from around the world (including Scotland), that would include an independent Scotland. However, the Thorp plant is due to close in 2018 when current contracts have been completed. This may create an issue with any remaining spent fuel in the UK, regardless of an independent Scotland. However, if either an independent Scotland or the remaining UK decided to reclassify ‘spent fuel’ as waste, this would remove the option to export waste for processing and would require an independent Scotland to develop additional infrastructure to deal with this new waste.

Further Reading

- BBC News – Who has a right to claim the North Sea?

- The Scotman – Legal warning of the North Sea

- A Forgotten Law and Policy Issue asIndependence Looms: Nuclear Waste Management in Scotland

- Financial Times (£) – Carbon capture scheme dragged into debate

- HM Government – Scotland Analysis: Energy

- HM Government – Scotland Analysis: Science and Research

- BBC News – Academics say ‘Yes’ vote could harm scientific research