Marion reports on the latest Grantham Institute for Climate Change special lecture by International Energy Agency Chief Economist Dr Fatih Birol.

On January 29th, I attended the Grantham Institute for Climate Change special lecture by International Energy Agency (IEA) Chief Economist Dr Fatih Birol at Imperial College London. Dr Birol discussed the future of the world’s energy market and outlined the main conclusions of the IEA World Energy Outlook report published in November last year. Here are the main points of Dr Birol’s lecture.

The long-held tenets of the energy sector are being rewritten

Trade patterns are changing and countries are switching roles, with long-established energy importers becoming exporters.

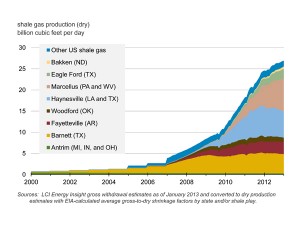

– The United States will soon become a significant gas exporter;

– Brazil is predicted to become a major net oil exporter around 2015;

– The Gulf States will increasingly export towards Asia.

US shale gas production, historical and projected – Source: US Energy Information Administration, Wikimedia Commons.

This is mainly due to the shale revolution and changes in nuclear policies of some countries following the Fukushima nuclear disaster. These new supply options are reshaping ideas about the distribution of resources.

However, long-term solutions to the global energy challenges remain scarce. There is a renewed focus on energy efficiency but CO2 emissions continue to rise. One problem remains the heavy subsidies of fossil fuel prices. These give an increased impetus to the consumption of coal, oil and gas and make it difficult for the clean energy industry to compete.

China is currently the main driver of the increased energy demand but India is predicted to take over in 2020 as the principal source of growth.

Most importantly, 1.3 billion people still lack access to electricity, mainly in Africa and South Asia, and the world must solve this problem.

What proportion of fossil fuels?

Twenty-five years ago, fossil fuels accounted for 82% of the global energy mix. It still accounts for 82% today, suggesting that reduction policies are not effective. Nonetheless, this number would perhaps be even higher if these policies were not in place.

The proportion of fossil fuels is predicted to decrease to 75% by 2035. They will still dominate in the near future, but the amount of renewables will increase.

With this fossil fuel energy mix, CO2 emissions will continue to increase and temperatures are set to rise by 3.6 degrees, which would have major environmental implications.

No more excuses?

As the most important energy consumer and CO2 emitter, it is very important that China be part of the future energy landscape. The country is currently relying on two premises to justify its share of global emissions:

1. Holding the past to account

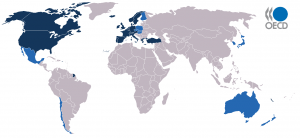

OECD member states (as of 2006) – Source: St. Krekeler, Wikimedia Commons.

The world cannot look only at today’s emissions but must take the past into consideration. The United States and the European Union became rich by using large quantities of coal to push the industrial revolution, so they bear the largest responsibility in today’s CO2 concentrations.

However, the responsibility of non-OECD countries will soon increase and will account for rising shares of emissions. It is thought that the energy consumption of non-OECD countries will be half that of OECD countries in 2035.

2. Emissions per capita over total emissions

With over 1.3 billion inhabitants, China’s total emissions are logically higher. The world must focus on emissions per capita.

However, models predict that Chinese consumption per capita will exceed that of some OECD countries next year.

We should be optimistic about Paris

The 21st session of the Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC will be held in Paris in 2015. We can be optimistic that world leaders will reach an agreement for three reasons:

Source: J.M. Schomburg, Wikimedia Commons.

– US emissions are decreasing, with current emissions at the level of those of the early 1990s. This is mainly a result of replacing coal with natural gas.

– Chinese increase in CO2 emissions has been one of the slowest in the past year. This is a result of decreasing coal consumption and investment into renewables. It is likely we will see limitations for coal consumption both locally and nationally in the near future.

– The EU is very active and remains committed to reducing emissions.

Can we achieve a 2 degree warmer world?

Under the current energy landscape, the world is not on track to keep average warming to 2 degrees by the end of the century. The IEA has outlined four energy policies that can keep this scenario alive, coined the 4-for-2 degrees scenario . These four policies could stop the growth of emissions by 2020 at no net economic cost and decrease emissions by 31 Gt, 80% of the saving required to be on track for a 2 degrees warmer world.

1. Implement new energy efficiency measures.

Targeted energy efficiency measures in buildings, industry and transport account for nearly half the emissions reduction in 2020. These will pay back within 5 years, with the additional investment required being more than offset by reduced spending on fuel bills.

The coal-fired Kintigh Generating Station in Somerset, New York – Source: Matthew D. Wilson, Wikimedia Commons.

2. Limit the use of inefficient coal power plants.

This would achieve more than 20% of the emissions reduction required and reduce local air pollution. The share of power generation from natural gas and renewables would increase in parallel.

3. Avoid methane escape during oil and gas production.

Emissions of methane (a strong greenhouse gas) during the production of oil and gas can easily be fixed with no negative economic impact. This requires a 0.6% investment for a reduction of half of methane emissions. This would provide 18% of the savings by 2020.

4. Partially phase-out of fossil fuel subsidies.

Implementing a partial phase-out of fossil fuel consumption subsidies would account for a 12% reduction in emissions.

There are four reasons to remain optimistic about the likelihood of implementing these policies:

– Political support: At the 2013 IEA Ministerial meeting in Paris in November, Energy Ministers agreed to push these measures forward.

– The US have declared they are committed to finding ways to remove support for inefficient coal power plants.

– The World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos revealed that several oil and gas companies were interested in cutting down their methane emissions.

– G20 countries are discussing fossil fuel subsidies.

What future for the energy sources?

Oil Rig at Port Khaled, UAE – Source: Basil D Soufi, Wikimedia Commons.

Oil: It was predicted last year that the US would surpass Saudi Arabia as the largest oil producer by 2017. It now seems that this will happen in 2015. This is not to say that this is the end of Middle Eastern oil. Shale oil in the US will grow but will almost exclusively be used nationally to meet the domestic consumption demand.

Consumption is also increasing in Asia and Middle Eastern oil is needed to meet this demand.

Renewables: The renewable energy market is growing everywhere in the world, especially in China. China is investing more in renewables than the US, all of Europe and Japan combined.

The expansion of non-hydrocarbon renewables depends on subsidies. Subsidies worldwide amount to approximately 100 billion USD, 60% of which are in Europe for on- and offshore wind and solar energy. This is set to double by 2035.

The issue of competitiveness

Before the shale gas revolution, gas prices between different regions were relatively similar. Now, EU and Japan natural gas prices are three and five times that of the US, respectively. This divergence will remain in place for many years, causing a structural issue for Europe and Japan. The big question now is if and how the EU will cope with this. Electricity prices are also increasing.

Location of Japanese nuclear power plants in 2006 – Source: PD-USGOV, Wikimedia Commons.

This divergence will impact the EU and Japan. Today, 52 Japanese nuclear reactors are stopped. The country is more reliant on imports and is recording its 17th month of trade deficit. Thirty million people in the EU are employed in energy intensive industries such as petrochemicals, aluminium and cement. This is a large portion of the EU’s economic output.

The change in energy prices will create clear winners (US, China) and losers (EU, Japan). If policies do not change, this will have a knock-on effect on the economy.

Conclusions

1) The global energy landscape is changing fast. Companies that cannot read these changes will become losers. Those who can see development coming and position themselves accordingly can benefit from this.

2) China and India will drive the growing dominance of Asia in the global energy demand.

3) New technologies are opening up new oil resources but the Middle East remains critical.

4) It is likely that the regional price gap for natural gas and electricity will remain significant for many years but there are ways to react. There is a need for efficiency policies to counteract these developments.

5) The transition to a more efficient, low-carbon energy sector is more difficult in tough economic times, but no less urgent.