In this week’s post, Flo talks us through the basic workings of the European Commission and how EU policy relates to science and research.

While the great and the good of academia are reaping the benefits of international research collaboration at EGU this week, and with the upcoming European elections in May I thought it was worth trying to write something on the EC and science policy. Especially as today’s theme at EGU was the role of geoscientists in public policy. Now I realise that I say ‘untangling EU science policy’ in the title but this is no mean feat!

The EC and its regulations can seem like an impenetrable fortress but it has a significant impact on UK policy and research funding. Senate House, inspiration for Orwell’s ‘Ministry of Truth. Source – Onona on Flickr.

Even for someone who works in policy, the EC and all its complex committees, processes and regulation can seem like taking a trip to an Orwellian-style ministry of information. Trying to understand and make sense of the EU regulation behemoth can feel like being lost in a bureaucratic miasma. Having said that it has a significant influence on the research and policy-making that goes on in the UK in terms of providing funding and regulation and I thought it would be worth highlighting what impacts membership of the EU has on science and funding.

The Basics

When it comes to decision making within the EU there are three important areas

- The European Commission – this is made up of 28 commissions, it has the ‘right of initiative’ and it implements EU policy and decides on the budget.

- The European Parliament – this has 766 members representing European Citizens (which we get to vote on) and is responsible for adoption of legislation and the budget as well as for democratic supervision.

- The European Council – this is made up of 28 ministers representing member states, is also responsible for adoption of legislation and and budget and in concluding international agreements.

The EC is then split into Directorate-Generals for which research falls into ‘Research and Innovations’. It also has other science-relevant remits such as energy, environment and climate action.

Research and Funding

Following the signing of the Lisbon treaty in 2007 the EU and its member states have a shared competency in the field of research and space which is largely exercised through funding. The EU decision makers, when it comes to research and innovation, are the Directorates of Research and Innovation and Education and Culture and in the Parliament, the Committees on Industry Research and Energy, and Culture and Education.

So how does this work in practice? Well, in terms of the science and funding elements of the system, it starts with the EU 2020 strategy and feeds down into implementation and funding.

The EU2020 strategy – one of the flagship initiatives is to to develop Europe as the most competitive and dynamic knowledge based economy in the world.

This feeds into the Innovation Union Flagship Initiative – this includes a series of ‘grand challenges’ such as Climate Change.

There is also the European Research Area (ERA) – this is an Europe wide single market for research, innovation and knowledge.

This then feeds into Horizon 2020, an EU funding programme for research and innovation.

The ERA is a ‘unified research area in which researchers, scientific knowledge and technology circulate freely’ and has an agenda with five main priorities:

- To create more effective national research systems, the UK already has a competitive research sector and the aim is to make other EU countries more competitive.

- Optimal transnational cooperation and competition – common research agenda on grand-challenges.

- An open labour market for researchers.

- Gender equality and gender mainstreaming in research to end the waste of talent not progressing into academia.

- Optimal circulation and access to and transfer of science knowledge including the development and implementation of open access to research results from projects funded by the EU Research Framework Programmes.

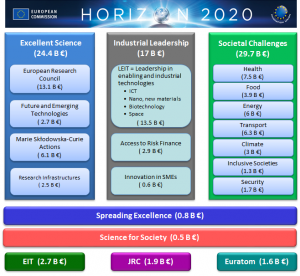

This all boils down into the Horizon 2020 – the EU framework programme for research and innovation which launched in January this year. Horizon 2020 is the biggest EU research and innovation programme ever with nearly €80 billion of funding available over 7 years, between now and 2020. It is the financial instrument implementing the Innovation Union initiative, which was a ‘Europe 2020 flagship initiative aimed at securing Europe’s global competitiveness’. Horizon 2020 has a greater focus on innovation compared to previous frameworks and is made up of a ‘3 Pillar Structure’ (see below image).

The three pillars of Horizon 2020 funding. Source – the EC website.

On the first pillar, where research money is delivered on the basis of excellent science only with no georaphical quota, the UK does very well (See this interesting article on the success of UK funding proposals) and was by far the most successful EU nation in winning grants from the European Research Council in the last round. As an example, the new National Graphene Institute at Manchester University was funded by the European Regional Development Fund who paid £23m of the £61m overall cost.

Horizon 2020 is open to everyone, and is designed with a simpler structure that reduces red tape. One of the many frequent complaints about securing research funding is the long application process which can be an institutional headache (not surprising really trying to harmonise processes in 28 member states!) and so the new funding round is due to deliver simpler application processes. It aims to develop the European Research Area to create a single market for knowledge, research and innovation. Horizon 2020 is the principal funding tool to realise the ERA, it funds all kinds of research.

In the case of countries that are not part of the EU, there are some collaborative projects and coordination between countries such as Iceland, Switzerland (although the situation with Switzerland has been up in the air for some time since their recent referendum on immigration quotas and how this interacts with the EUs freedom of movement directive) and Israel and the EU. These collaborative projects usually run for up to 5 years.

Examples of ERC funded projects in geoscience include: A century of climate change in South Asia, Marine Algae and the link between CO2 and past climate, World Water Week ERC projects, Corals and Climate Change, Evolutionary Biology, Developing marine-based sesimic-wave sensors, coring for CO2 in the Antarctic, how micro-fossils can help us understand climate change and many other topics.

Policy

When it comes to EU legislation, the EU can only do this where it has been empowered to do so by treaties. These are primarily in areas of trade. There are 3 types of EU legislation: (more on this here)

- Regulations – directly applicable to all member states and are binding.

- Directives – binding on member states but they decide how they should be implemented in order to achieve the required aim.

- Decisions – these are binding on whom they are directed to.

Like in the UK, the EC currently also has a top Chief Scientific Advisor, Scottish biologist Professor Annie Glover who was appointed in 2011 although there is a question mark as to whether that role will remain under the next President.

Important scientific areas that are regulated by the EU include Environmental and Climate Change Policy. In the Directorate-General of the Environment, there are policies on Air, Chemicals, Land Use, Marine and Coast, Soil, Waste and Water (including the water framework directive which the UK has adopted) and in Climate Change policy the important policy being the EU 2030 decarbonisation targets.

The EC holds extensive stakeholder engagement as part of its policy implementation through its public consultations, the themes of which are related to upcoming policy initiatives. Upcoming topics that are geo-relevant include Renewable Energy, Extractive Industries and Land as a Resource.

This is just an introduction to EU science policy, well done on making it to the bottom of the article: i’ll leave you with this, which popped into my head when thinking about this post!

Further Reading

Science Council Consultation Response: Government’s review of the balance of competencies between the United

Kingdom and the European Union – Research and Development

European Commission: Practical Guide to EU funding opportunities

BBC News: Horizon 2020 UK launch for EU’s £67bn research budget

European Commission: Open Consultations

NB: Some of the information in this post is taken from a presentation given by Lisa Bungeroth, Policy Officer at the UK HE International Unit.