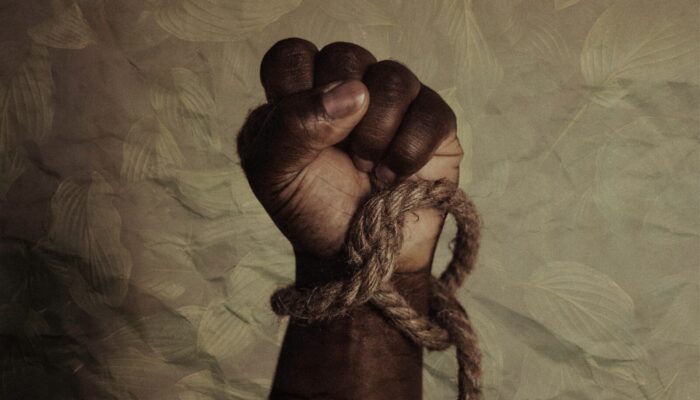

From 1525, when the first human trafficking ship departed Africa, to September 22, 1862, when the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, more than 300 years passed. This was enough time for the exploitation of humans and the earth to leave a permanent mark, one so profound it is now visible in the geological record. Not only did the age of chattel slavery during the Modern era shape the land and the environment until the 19th century, it continues to affect today’s industrial systems and our present and future climate.

Precipitation of imperialism on the American land

To describe the impact of human activity as a planetary force, the term Anthropocene was implemented. The Anthropocene is a geological epoch characterized by the clear presence of human traces in the stratigraphic record. These impacts range from changes in the atmospheric CO2 content, mass extinction, shifts and destruction of ecosystems, to the alteration of the surface geochemistry. Even though many of these interferences already happened in ancient times, imperialism took the anthropogenic impact to another level. One example of rapid alteration of the atmosphere chemistry is a negative peak of 7-10 ppm in the atmospheric CO2 content, recorded in ice cores from Antarctica. This sudden descent is interpreted to be linked to the killing of more than 50 million indigenous people in the Americas by European imperialists and settlers. War, famine, and diseases eliminated the people who practiced farming and used small fires for deforestation.

Colonialization also disrupted sustainable land use, which was followed by a decrease in atmospheric CO2. This serves as an example of the deadly impact of imperialism on the native American population and culture, but also enhances the mendacity of the tale of a “savage” and “untouched” land, which was later used to justify the extensive plantation farming and mining business. When settlers arrived in the Americas, they brought shiploads of new biota with them. The Colombian Exchange, written by Alfred W Crosby, describes the first steps of a rapid, global homogenization of goods and life. The author claims that domesticated animals, seeds, insects, other small animals, bacteria, and viruses were able to suddenly bypass the natural barrier of the Atlantic Ocean. These intentional or accidental introductions altered the ecosystems in the Americas, Europe, and Africa.

A layer of extraction

European imperialism exploited land, the Earth, and people with the same level of exhaustiveness. Before Europeans enslaved and forcibly deported Africans to work on annexed territories, Indigenous Americans were coerced into working in mines and on plantations. The case of silver mining at Cerro Rico in Potosí, Bolivia, illustrates how the labor and centuries-old knowledge of Inca miners were used to expand its output. Potosí subsequently became the world’s largest silver producer, a position it held from the start of large-scale mining in 1545 to the mid-18th century. The largest profiteer was Spain as the colonizer of South America, but other European powers were involved in the trading of silver from Potosí as well. This global trade played a crucial role in globalizing the market of natural resources.

Furthermore, Potosí is a cornerstone for environmental destruction due to the use of the mercury amalgamation process. When high-grade surface silver ores were exhausted (native silver and chlorargyrite (AlCl)), mercury amalgamation processes were implemented to extract silver from low-grade ores (e.g. argentite (Ag2S)). In simplified terms, the ores were crushed and mixed with mercury to form an amalgam of mercury and silver (or gold). This amalgam was then heated to evaporate the mercury, and almost pure silver was left. Large amounts of mercury were lost during this process, even though it was aimed to be captured for economic reasons. Mercury was discharged into waterways, deposited in the ground, and released to the atmosphere. The latter being the main affected sphere with an estimated uptake of 60-65% of the mercury, used in silver and gold mining in the Americas during the 16th to the 19th century. The residence time of mercury in the atmosphere of 6-18 months, and its volatility enables a global cycle of mercury pollution. As a neurotoxin, mercury exposure and intake through the air or contaminated food present a severe health risk, and miners received no protection in any form. During the gold rush in the U.S., mercury amalgamation was a commonly used step in the processing, and “[…] enslaved miners suffered from mercury poisoning, both from working with the liquid form with their bare hands and from inhaling fumes during distillation.” says Silkenat, David. Although the toxicity of mercury was already reported in 50 B.C. in Asia, by the Romans in AD 79 (see “Naturalis historia” by Pliny the elder), and in 1556 in Georgius Agricola’s work “De re metallica”, the severe harm done to the environment and endured by enslaved people was accepted for a short-term profit.

This destructiveness is also deposited in the soil by plantation farming during slavery in Modern times. To recognize the ongoing impact of Plantation driven agriculture by the exploitation of people, the term Plantationocene was introduced in 2019. Tobacco was one of the most widely grown crops in the Americas from the 17th century until the 19th century. Tobacco is also a plant with a high demand for nutrients, growing best on fresh soil but also depleting it quickly. By exploiting both the myth of endless, “free” land and the dehumanizing concept of racialized chattel slavery, European Americans rapidly expanded their plantations, subjecting enslaved people to extreme and brutal exploitation. Used land was abandoned when it became infertile due to unsustainable cultivation, and new areas were harshly developed for agriculture. Additionally, soil leaching and deforestation left their marks on the environment. Not only did this impact the ecosystems, but the missing vegetation led to erosion of the most fertile layers by soil runoff. Consequently, ecosystems were permanently altered, rivers got clogged and muddy, and the soil loss was nearly irreversible: “It takes a thousand years to regenerate 3 centimeters of topsoil”, wrote R.L. Martens and Bii Robertson.

The search for fertilizers in the U.S. began in the first half of the 18th century, often enhancing the labor of enslaved people. First, mineral resources such as marls and sandstones were quarried and tested in the field, and later, guano proved to be a promising fertilizer. Through guano, nitrogen, an index proxy for the Anthropocene, got enriched in the soil to detectable levels – another precipitate of the exploiting slavery system. Even though guano was not used widely, as noted by the Geological Survey of North Carolina in 1858, the need to re-fertilize the sterile land, even if only short-term, was inevitable to further exhaust it.

Enrichment of a few by depleting Earth and people

“We learned that as plantation owners in Maryland tried to extract the most profit from the land and the most labour from the people they owned [sic], the soil often became so depleted of nutrients that it would no longer produce. It “rebelled.” Extracting labour from Black people was not exhausted as quickly as the land. Racist ideology enabled the slavery system to exploit people ongoing and beyond the acres of the plantation owners. The mining business in North America peaked during the gold rush in the 19th century. It opened a field independent from soil and harvest, and enslaved people of African descent were compelled to work in the mines, often doing the most dangerous jobs. It is important to recognize that not only was labour exploited from enslaved Africans, but also knowledge. Indigenous gold mining was part of the West African cultures and economies since the 9th century. Enslaved Africans “contributed to the development of new mining techniques” and had skills in mining gold, silver, and other crucial geomaterials. The “enormous profits [for European Americans derived from the gold rush] came at a tremendous environmental cost and risk to enslaved miners”. The labour of enslaved people changed the geomorphology. Placer mining altered river courses, and stream beds were dug down to the basement. The environmental destruction is “the extreme violence dealt to Black bodies [that] is recorded on the earth.”

The ongoing extraction of labour and its effects on our environment

Geology is teaching us: the past is constituting our present. The exploitation of humans, their dignity, work, and life, during slavery from the 16th to 19th century, paved the way for present monocultures and modern exploitation of the earth. When the first steps were taken to finally abolish chattel slavery in the U.S. on the 22nd of September 1862, the ‘Plantationocene’ was far from over. Today, we live in a world in which industrialized agriculture and mining are dictating the environment globally. Hence, contemporary anthropogenic impacts on the geomorphology are shaped by the environmental legacies of slavery during Modern times. Understanding the link between the exploitation of the Earth and people should make it clear that modern slavery, environmental issues, and climate change are reinforcing each other.