When a tremor shakes the ground, the first thing many people do isn’t check a scientific database: they reach for their phone. Within seconds, searches like “earthquake near me” surge across Google. This simple phrase captures something profound: a universal need not to understand seismic mechanics, but to know “Am I safe?” Over the past few years, this “near me” framing has quietly reshaped how the public interacts with science. It connects global-scale data to local, personal relevance, but also reveals a persistent gap between how scientists describe hazards and how people seek to understand them. That gap inspired EarthquakeNearMe.org, a simple real-time dashboard that translates complex seismic feeds into accessible, location-based updates for the public.

The rise of “Near Me” science searches:

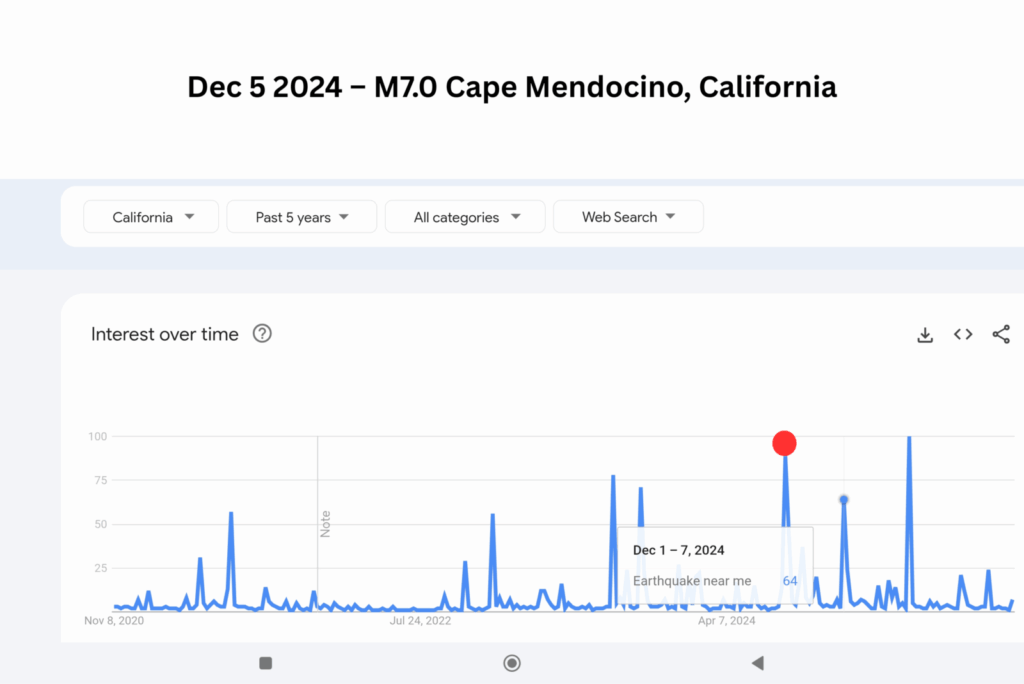

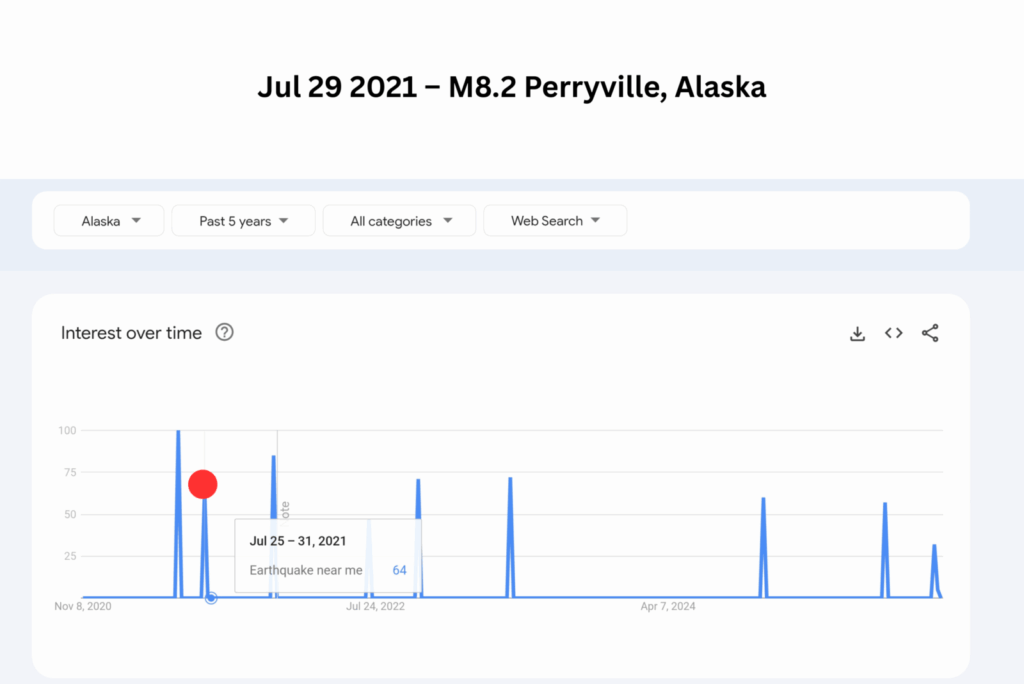

Google Trends shows dramatic spikes in “earthquake near me” queries following major seismic events — often outpacing official communications. The same happens with “wildfire near me,” “flooding near me,” and “hurricane near me.” For science communicators, these search patterns offer valuable insight: they show how, when, and why people seek information during crises.

The problem is that much of the data available at those moments, waveforms, depths, and magnitudes, isn’t designed for non-specialists. Scroll through social media after an event, and you’ll see the confusion firsthand. One post during the July 2024 California quake read:

“My app says magnitude 3.6, another says 5.1! Which is it?!”

Another user asked:

“If the epicentre’s 100 km away, why did my whole house shake?”

These are not signs of ignorance, but signs of an information gap. People are trying to make sense of scientific data through the tools they have, and often those tools don’t speak the same language as scientists do.

Jul 29 2021 – M8.2 Perryville, Alaska Dec 5 2024 – M7.0 Cape Mendocino, California

Search interest in “earthquake near me” surges within minutes of major events.

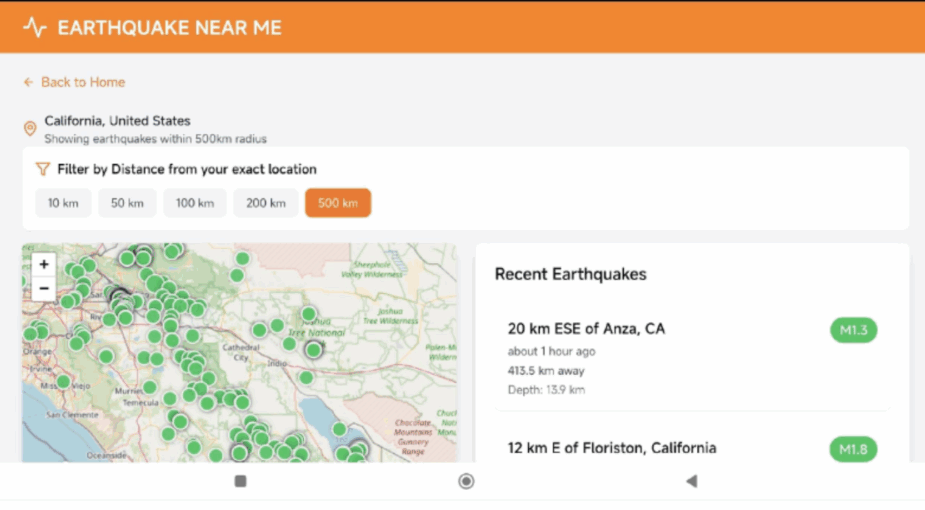

From Data Streams to Human Meaning Modern seismic networks produce immense volumes of real-time data, essential for researchers, but often unreadable to the public. EarthquakeNearMe.org simplifies this by distilling key questions anyone can understand: Where was it? How strong was it? Did others feel it? Is there any ongoing risk? Instead of technical summaries, the platform offers human context: “Light shaking, unlikely damage,” rather than just “Magnitude 4.8.” The goal isn’t to oversimplify, but to help people interpret what matters most to them in that moment. Balancing scientific precision with clarity is the hardest – and most important – part of hazard communication. It’s the art of making science useful under pressure.

The civic-tech connection

Civic technology — digital tools built on open data for public benefit — has become an unsung ally of science communication. From pandemic dashboards to flood alerts, civic-tech platforms turn raw datasets into something people can actually act on. Many of these initiatives, however, come from small independent teams rather than research institutions. That opens a space for collaboration: scientists can guide data accuracy and context, while developers ensure usability and real-time reliability. When done well, this partnership transforms how the public experiences science — from something distant and technical to something immediate and empowering.

Clarity builds trust

Simplification is not distortion; it’s translation. A magnitude value or hypocentral depth may be technically correct, but it doesn’t help someone decide whether to check for structural damage or reassure a child. Framing data in plain language builds trust, and trust, more than any figure, shapes how people respond to scientific information. When scientists join forces with communicators and developers, they bridge the emotional gap that often separates data from decision-making. That bridge is where resilience begins.

A shared language for uncertain times

EarthquakeNearMe.org is a small project, but it reflects a much larger shift: the move toward human-centered science communication. People don’t search for “moment tensor solutions.” They search for “earthquake near me.” This linguistic clue tells us something powerful: the public doesn’t want less science, they want science that feels close. If scientists, communicators, and civic technologists can listen to that signal and meet it with empathy and clarity, we can transform moments of fear into opportunities for understanding. In the end, “near me” is more than just a search term, it’s, in fact, a reminder that science matters most when it meets people where they are.

EarthquakeNearMe.org transforms open seismic data into clear, localised insights anyone can access in seconds.