Today, as we mark the anniversary of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), founded in Baghdad on September 14, 1960, by five oil-producing nations: Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, and Venezuela, and with the European Union setting ambitious climate targets for 2040 , the global energy landscape stands at a critical juncture. A century profoundly shaped by fossil fuels is giving way to an unprecedented imperative for transformation, driven by the escalating climate crisis and evolving geopolitical dynamics. This era of “petro-power,” where organizations like OPEC have historically wielded immense influence over global economic trajectories and international relations through their control over oil supply and prices, is increasingly challenged by the accelerating clean energy transition. This analysis offers a strategic foresight into 2040, a pivotal year given the European Union’s ambitious climate targets, exploring two polarised pathways: one where proactive, systemic change is embraced now, and another where meaningful action is delayed or ignored. The political, economic, and social implications of each scenario will be examined through the lens of Cara Daggett’s concept of “petro-masculinities.”

The enduring grip of oil: A legacy of power and identity

OPEC’s genesis and influence

OPEC’s formation in 1960 was a direct response to major oil companies unilaterally reducing Middle East crude oil prices. The organization’s foundational mission was to coordinate and unify the petroleum policies of its member countries, stabilize oil markets, and ensure a fair and stable selling price for producers. This historical context is essential for understanding the origins and evolution of resource nationalism within the oil sector.

The formidable influence of OPEC became evident during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, when Arabic OPEC Member States unilaterally increased crude oil prices by 70% and imposed a monthly reduction in oil production, alongside an embargo on oil supply to the United States and Western Europe. This led to a quadrupling of the “light Arabian” crude oil barrel price within a few months. Although the embargo lasted only five months, it triggered a two-year economic crisis and permanently altered global energy dynamics, which shows the profound vulnerability of oil-importing nations. The 1979 oil shock, worsened by the Iranian revolution and the onset of the Iran-Iraq war, saw prices triple again, precipitating another severe economic crisis that endured until 1983. These events solidified OPEC’s role as a potent geopolitical actor, capable of wielding significant economic and political influence.

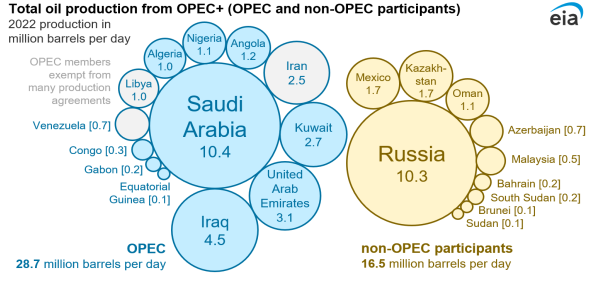

Today, OPEC, along with the expanded OPEC+ alliance, controls approximately 40% of global oil supplies and over 80% of proven oil reserves, granting them considerable short-term leverage over prices. However, their long-term ability to dictate prices is increasingly diluted by differing national incentives among members and the overarching forces of global supply and demand. Historically, OPEC’s power derived from its capacity to control supply and thus price. Yet, recent events, such as the COVID-19-induced demand slump in 2020, demonstrated that even OPEC+ cannot entirely override fundamental supply and demand dynamics, which leads to significant price crashes. This indicates that while OPEC can influence short-term volatility and establish a price floor, its capacity to dictate the long-term trajectory of a declining market is constrained by global demand shifts and the proliferation of alternative energy sources. Consequently, the future of OPEC’s influence will depend less on its ability to control supply in an expanding market and more on its capacity to manage decline in a shrinking one, while simultaneously adapting to the diversification of global energy sources. This dynamic could foster internal tensions within OPEC as members pursue divergent strategies, potentially weakening its collective power over time.

Resource nationalism, characterized by states seeking direct and increasing control over their natural resource sectors, has been a persistent theme in oil and gas politics. This phenomenon is driven by a desire to maximize revenue, assert national sovereignty, and push back against the perceived power of multinational corporations. It manifests in various forms, from contract renegotiations and demands for increased national shares in joint ventures to outright nationalization of oil and gas sectors.

The uneven global distribution of fossil fuels has long impacted international relations worldwide. Consequently, this created dependencies where countries lacking sufficient domestic resources must rely on imports from politically (intentionally turned) volatile regions. Even as the world transitions towards renewable energy sources, the geopolitics of resources remain critical. The transition itself introduces new resource dependencies, especially on critical minerals that are necessary for clean energy technologies. This means that a post-petroleum future cannot be resource-agnostic, but will rather be one with a reconfigured resource landscape.

The historical geopolitical leverage enjoyed by oil-rich nations is indeed being challenged by the energy transition. However, this transition is not about eliminating resource dependence but rather shifting its nature. The massive scale-up of renewables necessitates a significant increase in demand for critical minerals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, and copper. This new dependency creates new geopolitical vulnerabilities, as the supply chains for these minerals are concentrated in a few countries. For example, China’s dominance in solar panel and battery production grants it considerable leverage. Therefore, a post-petroleum future will not be free of resource geopolitics; instead, it will feature a new, what I will call here, mineral geopolitics. Nations that control the extraction, processing, and supply chains of these now sought-after minerals will acquire new forms of leverage, which may potentially (if not very likely) lead to new trade disputes, intensified competition, and the formation of novel strategic alliances. This necessitates a proactive approach to diversifying supply chains and promoting ethical mining practices to avoid simply replacing one form of resource dependency with another.

Petro-Masculinities: The cultural undercurrent

Cara Daggett’s concept of petro-masculinity provides a vital framework for understanding resistance to the energy transition. It posits a strong connection between gender hierarchies (or gender domination), the exploitation of energy (extracting fossil fuels), and political power. This theory moves beyond purely economic or technical explanations for climate inaction.

Daggett argues that new authoritarian movements in the West embrace a “toxic combination of climate denial, racism, and misogyny,” where fossil fuels represent more than just profit; they contribute to the formation of identities. This helps to explain the rise of leaders who frequently employ anti-gender and pro-fossil fuel narratives. Daggett developed this term to highlight how the misogyny and anti-feminist gender politics prevalent on the right are inmeshed with fossil fuel politics and climate denialism. This challenges the liberal framing that separates personal politics from broader economic and environmental issues. This ideology suggests that fossil fuel usage is symbolically associated with authoritarian norms, thereby strengthening resistance to climate legislation among specific populations. Climate denialism, within this perspective, becomes embedded in wider ideological conflicts, including cultural disputes over scientific authority, environmental regulation, and personal freedoms. The psychological unease associated with recognizing climate accountability can also lead to defensive denial.

Petro-masculinity approaches masculinity as a socially constructed identity that emerges ‘within a gender order that defines masculinity in opposition to femininity, and in so doing, sustains a power relation between men and women as groups’. Masculinities are always multiple, and involve ongoing struggles over which version of masculine identity will become socially dominant, or hegemonic, to adopt R.W. Connell’s influential concept. Petro-masculinity draws upon aspects of a traditionally hegemonic masculinity, but at the same time, its appearance in the American far-right today is better understood as a kind of hypermasculinity, which is a more reactionary stance. It arises when agents of hegemonic masculinity feel threatened or undermined, thereby needing to inflate, exaggerate, or otherwise distort their traditional masculinity. Wrote Daggett

The resistance to energy transition is not purely economic or technological; it possesses cultural and psychological dimensions. Petro-masculinity explains how reliance on fossil fuels is intertwined with notions of independence, productivism, and a specific form of hierarchical, dominating masculinity. This identity-based resistance, further amplified by misinformation campaigns from fossil fuel industries and conservative think tanks, renders policy changes incredibly difficult, even when they are economically rational. For some, relinquishing fossil fuels is perceived as a loss of identity or power. Therefore, effective energy transition strategies must extend beyond purely technical or economic solutions. They must also address the underlying cultural narratives and identity politics that fuel climate denial and resistance.

The path to 2040: Two divergent futures

Scenario A: Changing now

This scenario envisions a future shaped by decisive policy action, accelerated technological adoption, and a collective commitment to decarbonization, aligning with ambitious targets like those set by the European Union.

Global commitments and momentum

The European Union is a leading example in setting ambitious climate targets, having proposed a legally binding 2040 climate target of a 90% reduction in net greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions compared to 1990 levels. This builds upon an existing 2030 target of at least a 55% reduction. This target is aligned with the EU Competitiveness Compass and Clean Industrial Deal as it provides crucial predictability for investments in clean energy. Achieving such an ambitious target necessitates a “massive expansion of renewable electricity generation, drastic reductions in fossil-fuel use, energy efficiency measures, and deep electrification of end-use sectors”.

Globally, significant momentum is evident. 2023 witnessed record growth in renewable electricity capacity additions, with approximately 560 Gigawatts added, two-thirds of which originated from China. Solar PV alone accounted for about 70% of this substantial growth. The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) estimates that 90% of the world’s electricity can and should be derived from renewable energy by 2050.

The EU’s ambitious 2040 target is not merely an internal objective; it is explicitly presented as a “clear lighthouse” and a signal to the global community, which demonstrates its commitment to the Paris Agreement. By establishing stringent targets and implementing pioneering policies such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), the EU is decarbonizing its own economy and also actively shaping global trade and investment flows towards cleaner technologies. This creates a “first-mover advantage” for EU businesses and stimulates innovation worldwide. This proactive stance by the EU creates a powerful feedback loop, since its targets stimulate internal innovation and investment, which in turn lowers costs and improves the feasibility of clean technologies globally. This makes it easier for other nations to follow suit and positions the EU as a significant geopolitical force in shaping the global energy transition.

Technological readiness and innovation

Clean energy technologies such as solar, wind, energy efficiency solutions, and electric vehicles are now “well established and readily available”. Energy storage is essential for managing renewables, with global capacity expected to exceed 2 TWh by 2030, though more innovation and investment in batteries and smart grids are needed. Around 35% of future emissions reductions depend on emerging technologies such as hydrogen fuels, small modular reactors, and advanced carbon capture. Despite technological readiness, policy gaps hinder progress. Current policies only capture about one-third of potential energy savings. The main barrier to accelerating the energy transition is not technology but insufficient policy support. Stronger frameworks, incentives, and investments are therefore required to unlock the full potential of clean energy and ensure innovations can scale effectively.

A just energy transition to a post-petroleum future

The global shift toward clean energy is an environmental necessity and a fundamental economic and geopolitical transformation. Accelerating this transition offers significant economic and social gains, which can reshape humanity’s future for the better. For instance, an accelerated transition could save households hundreds of dollars annually and prevent millions of premature deaths from air pollution. Beyond these direct benefits, a move away from fossil fuels enhances national energy security, protects economies from volatile price shocks, and frees up household income, particularly for low-income families who bear the brunt of energy costs.

This transition is driving a major geopolitical shift. As nations electrify, reliance on fossil fuel producers diminishes, and influence moves to countries rich in renewables and the critical minerals essential for clean technologies. Energy trade is shifting from a global, oil-centered system to a more regional and independent one. Yet this brings new vulnerabilities, particularly with soaring demand for minerals like lithium, cobalt, and copper. The rise of mineral geopolitics, which can be observed in China’s dominance in solar and battery manufacturing, creates fresh global dependencies. To prevent one form of reliance from replacing another, countries must diversify supply chains, expand recycling, and strengthen cooperation to secure resilient and ethical resource networks.

This transformation, however, cannot go ahead unless it’s moving in parallel with energy justice. This means ensuring the clean energy shift is fair and inclusive on a global scale, especially for the countries whose resources were robbed (and are still being robbed) due to (neo)colonialism.

Scenario B: Delayed Action and the cost of inertia

This scenario explores a future where insufficient policy action and continued reliance on fossil fuels lead to escalating crises and missed opportunities…

Continued fossil fuel dependence

If current policies and trends persist, global energy demand is projected to grow by over 25% by 2040, primarily driven by rising incomes and population growth in emerging economies. In this trajectory, oil and natural gas are projected to remain essential, meeting over 50% of global energy demand by 2050. Oil consumption is forecasted to continue increasing since it’s driven by rising demand in petrochemicals, trucking, and aviation. Natural gas is expected to become the second-largest fuel in the global energy mix by 2030. This scenario implies continued high investment in fossil fuel supply, with significant production growth expected from regions like North American shale and the Middle East.

The IEA projects that under current and planned policies, energy-related global CO2 emissions will continue to grow to reach new record highs. A significant portion of these emissions is locked in by existing fossil fuel infrastructure, particularly coal-fired power plants, predominantly in Asia, which average only 11 years of age and have decades more to operate. Delaying action means these assets continue to emit and make future climate targets harder and more costly to achieve, as CO2 accumulates in the atmosphere. The inertia of existing fossil fuel infrastructure thus creates a challenging barrier to decarbonization. Without aggressive policies to accelerate the phase-out of these assets or mandate widespread carbon capture technologies, the world will be locked into a high-emissions pathway, rendering the 1.5°C global warming target increasingly unattainable and necessitating far more drastic and expensive measures in the future.

Escalating climate impacts

Delaying climate action directly increases atmospheric CO2 concentrations and leads to persistent and compounding economic damages from higher temperatures, more acidic oceans, and increasingly severe extreme weather events. A policy delay resulting in global warming of 3°C above pre-industrial levels, instead of 2°C, could increase economic damages by approximately 0.9% of global output, equivalent to roughly $150 billion for the US GDP in 2014, and these costs are incurred year after year due to permanent damage. The changing climate accelerates multiple threats, including more severe storms, droughts, heat waves, further sea level rise, and the degradation of natural systems vital for life, water resources, and food production. Beyond economic and environmental costs, there are direct health risks: Think of how extreme heat endangers older people, how melting glaciers could reawaken ancient pathogens, and how floods threaten the release of dangerous chemicals.

Economic stagnation and vulnerability

While delaying action might appear to reduce costs in the short term by avoiding expenditures on new pollution control technologies, this short-term advantage is significantly outweighed by long-term disadvantages. Net mitigation costs increase by approximately 40% for each decade of delay, as more stringent and thus more costly policies become necessary to meet targets. Continued reliance on fossil fuels leaves economies highly vulnerable to volatile price swings and geopolitical shocks, as vividly demonstrated by the 2022 energy crisis. This unpredictability hinders long-term economic planning and investment. Economies that delay transition will miss out on the massive opportunities for job creation and economic growth in the burgeoning clean energy sector, which could lead to ceding leadership and competitive advantage to proactive nations. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects that in a “fast adoption scenario” for electric vehicles, oil prices could converge to the level of coal prices (around $15 per barrel in 2015 prices) by the early 2040s. This implies a significant risk of stranded assets for oil and gas companies and nations that fail to diversify their economies.

Choosing our 2040

By 2040, humanity will have solidified its future through the choices we make today. We can choose a proactive path, one fueled by bold policies and rapid innovation, which promises a more stable climate, stronger economies, and a more equitable society. While this transition will be challenging, it offers immense opportunities for growth and prosperity. Alternatively, we can continue on the path of delayed action, defined by a dangerous reliance on fossil fuels, escalating climate impacts, and persistent global instability. This choice would lock us into a future of compounding crises, where the costs of inaction far outweigh any short-term savings. The good news is that the solutions already exist. As geoscientists, you are undoubtedly positioned to help lead the way. Your expertise in Earth systems is essential for everything from locating new clean energy resources to safely storing carbon. Your work will be critical in building a resilient and sustainable energy system for everyone. The choice is ours, and the time to act is now.