Imagine losing your land – little by little – to deep, destructive trenches carved by rain and flowing water. This is what gully erosion does, a problem that has been devastating several communities worldwide. Ethiopia’s Aba Bora Watershed, the subject area of a recent study published in the EGU open access journal, SOIL, is located in the Oromia region and is a part of the larger Baro-Akobo River Basin, which contributes to the Nile River. This watershed supports diverse ecosystems and is crucial for local agriculture and biodiversity, where over 80% of households depend on farming. The researchers who conducted this study investigated the effectiveness of low-cost, community-based gully rehabilitation strategies, focused on the implementation of three different gully treatments, and examined the role of farmer involvement in on-farm trials.

Their research posed three key questions:

- How effective are affordable gully rehabilitation methods in stopping erosion?

- How do farmers and communities perceive these strategies?

- Does involving farmers in field trials enhance their knowledge and willingness to act?

Here’s how this research unfolded, and what it means for other regions facing similar challenges.

What happens when soil disappears? Livelihood follows…

Gully erosion is a relentless force. As water cuts through the earth, it forms deep channels, strips away fertile soil, and leaves farmland barren. In Aba-Bora, where fragile Luvisol soils are prone to erosion, deforestation and intensive farming practices compound the problem. Without intervention, these gullies grow wider and deeper, and the consequences include reduced crop yields, degraded pastures, and a constant threat to food security.

The challenge in the watershed is emblematic of a larger issue: communities around the world face similar battles, especially where resources and knowledge to combat soil erosion are scarce. The question isn’t just how to fix the problem, but how to do so in a way that’s affordable, sustainable, and feasible for smallholder farmers

So, what are the solutions proposed by this research?

To tackle the problem, the authors tested three low-cost rehabilitation methods designed to stabilise gullies and stop soil loss:

- Stone riprap: Placing stones at the gully head to slow water flow.

- Stone + grass: Adding grass along the gully’s banks to reinforce stability.

- Stone + grass + sandbags: Combining stones, grass, and small sandbag dams for maximum impact.

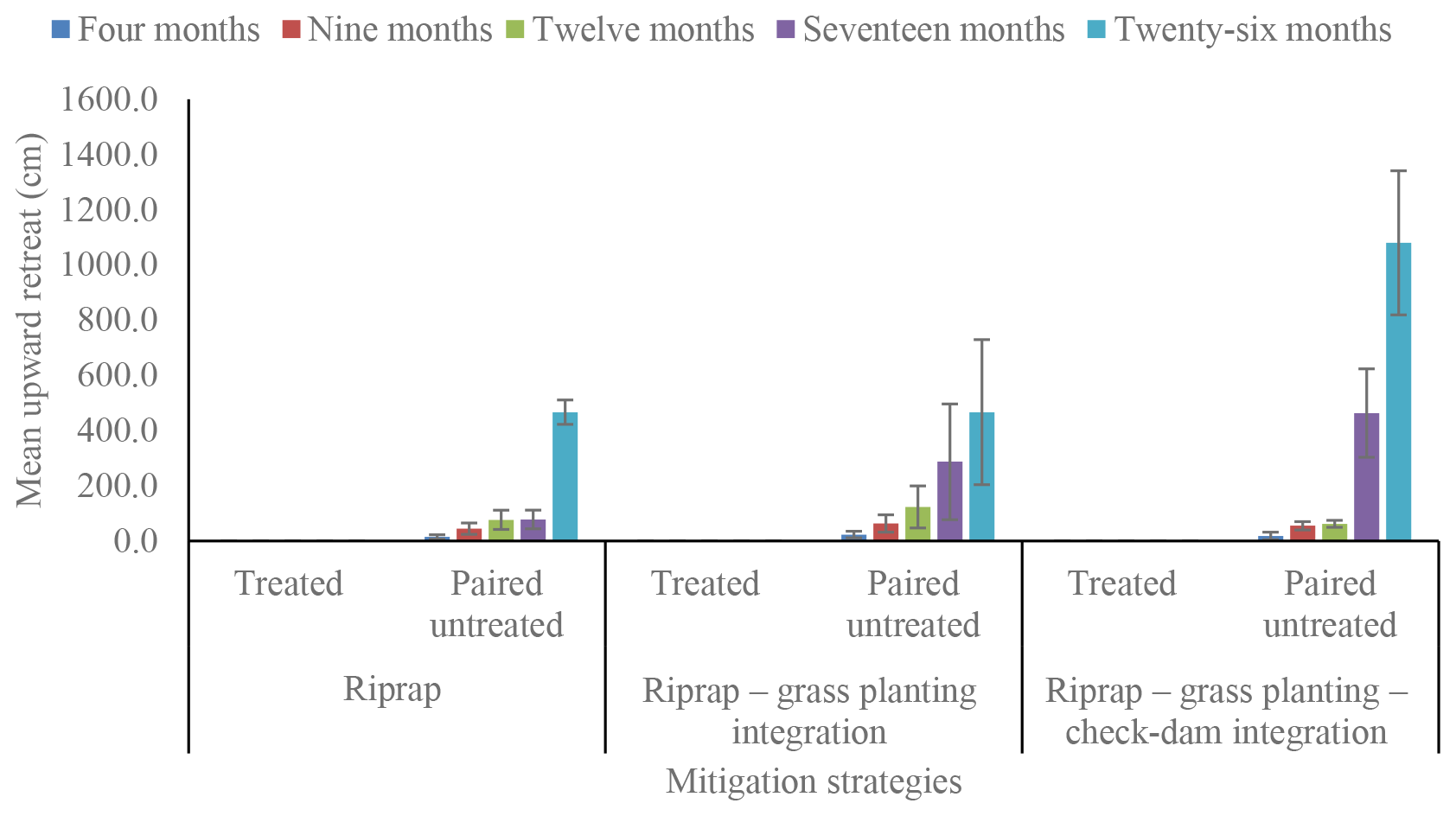

The mean upward expansion of gully heads in the treated and paired untreated gullies as described in the study design. The paired untreated gullies accounted for their spatial distribution, where a grouped control site would introduce variability due to slight changes in climate or soils. For all treated gullies, the values for the upward expansion of gully heads was negligible.

The team selected nine gully pairs, each with similar conditions, and treated half while leaving the others as controls. Over 26 months, they tracked soil loss and gully expansion while measuring the impact of these interventions.

But this study wasn’t just about numbers – it was about people. Farmers participated in field days, where they saw the treatments being conducted first-hand. Interviews, group discussions, and household surveys gauged their knowledge, perceptions, and willingness to adopt these methods. Farmers, in this study, were treated as partners rather than passive subjects.

Can such small changes have a huge impact? You bet!

The findings of this paper were striking! In treated gullies, soil loss stopped entirely, while untreated ones continued to grow dramatically. This is strong proof that even basic interventions could halt erosion.

Beyond the physical results, community involvement was key in this study. Farmers who participated in field trials gained a deeper understanding of erosion control techniques, and their willingness to act increased significantly. For example, treated areas saw a 40% rise in farmer-led efforts to manage erosion. People didn’t just learn about solutions – they began applying them, despite their awareness of the challenges involved. As the saying goes ‘Many hands make light work’, the same applies when we equip farmers with simple tools, local knowledge, and a shared commitment to protecting the land; they can mend even the deepest wounds in the earth.

Local farmers had their opinions about these solutions.

While the interventions were effective, they also highlighted the complexities of scaling up these solutions. Farmers acknowledged that low-cost methods like stone and grass treatments were manageable, but some measures – like sandbag check-dams – required resources they couldn’t always afford. Economic barriers are what seem to be a main factor. For instance, the high cost of materials like gabion wires limited their use, even though they’re highly effective. Additionally, gender had an impact on this the benefits of these interventions were received. Some men, who are often responsible for financial decisions, expressed more concerns regarding expenses, while some women prioritised improvements in water access, as they typically manage water collection. This gendered observation is one of the reasons why inclusive planning is of high importance. Solutions need to account for diverse community perspectives and ensure that everyone – regardless of gender or economic status – has a voice in the decision-making process.

What does this study teach us?

The value of early intervention is one of the key lessons of this study. While the fight against gully erosion is far from over, the Aba-Bora watershed study offers an excellent example of what’s possible, such as how tackling small, shallow gullies is much cheaper and easier than rehabilitating large, deep ones. This means that starting early not only saves money but also increases the likelihood of long-term success. Another critical lesson is the need for locally tailored solutions. This means if the community opts for materials that are readily available, such as stones and grass, the interventions become accessible and affordable.

[…]beginning gully reclamation at an early stage is important as reclaiming big gullies with other measures, such as loose-rock and gabion check-dams, is costly and difficult for smallholder farmers to manage considering their financial and technical capacities. (Wolde Mekuria et al)

The authors of this paper are also offering hope for other regions that are struggling with gully erosion, since similar low-cost approaches have shown promise in places like the Ethiopian highlands and Pakistan. In these regions, community-driven solutions have helped restore degraded lands and improve agricultural productivity. This proves that with the right support, communities around the world can replicate the success demonstrated in this paper, and can start turning the tide against soil erosion.

Policymakers, you need to act too.

For policymakers and development organisations, the message is clear: invest in small-scale, practical interventions that communities can implement and maintain themselves. This means that now is the time to prioritise funding and resources for interventions that align with the realities of smallholder farmers. Large-scale, capital-intensive projects often fail to resonate with rural communities because they are financially inaccessible or poorly adapted to local contexts. Instead, small-scale, community-driven approaches – like those tested in this study – offer a viable path forward.