The International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, observed each year on August 9, seeks to raise awareness and protect the rights of indigenous communities around the globe. To honour this, I have invited a few guest authors to write a series of blog posts that celebrate indigenous knowledge and highlight the intersection of natural hazards and climate issues, and resilience, across various indigenous groups worldwide. These communities offer unique perspectives on the relationship between humans and the natural world—perspectives that are often rooted in centuries of living in harmony with their environments. This blog post seeks to explore one such relationship: the intimate and enduring bond between the Aldeia Maraka’nà, an indigenous community nestled in the vibrant city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and its lifeblood—the river.

Aldeia Maraka’nà, though situated in one of the world’s most bustling urban centres, maintains a deep connection with its natural surroundings. The river that flows through this community is more than just a body of water; it is a source of sustenance, a sacred entity, and a living symbol of the community’s history and identity. For the people of Aldeia Maraka’nà, the river represents a profound link to their ancestors and their way of life, embodying the complex relationships that define their existence.

Headwaters

The history of human societies is always a history of their interactions. The formation of social groups, such as ethnic groups, is based on interactions established between the group’s actors, sharing valuation and judgment criteria, and actors outside the group, from where distinctions are fixed (Barth, 1976).

Ethnicity itself can be understood as an aspect of human interaction, in addition to a property of this particular social formation, which is ethnic groups. Some of these interactions also occur between humans and non-human. According to Sophie Houdart, human reality is enveloped by the environments in which it unfolds. The environment threatens, involves, and allows life, creates differentiation and belonging, or, in other words, establishes relationships between its elements and with humans. A fundamental aspect of this environment is water and the interaction that humans establish with it. The human-water relationship can be seen as one where water provides a vital natural resource, essential to life. However, water itself is also a non-human actor, engaged in an ongoing and evolving relationship with human actors.

The ambiguity here can be clarified by specifying what “collective representations” refers to. Here’s a rephrased version:

These relationships between humans and non-humans typically form the foundation of the aforementioned native or indigenous worldviews and cosmogonies, which shape both their territories and their collective representations of those territories. Such a view does not involve a legal-political notion of territory, which results from a specific conception inherited from the Modernity of the nation-state. Rather, it is a concept of territory as a set of objects and actions, synonymous with human and inhabited space, which can be formed in the contemporary period by contiguous places and networked places. Therefore, this territory is a political and historical construction, it is the ground plus the identity, with territoriality being a quality of belonging to this ground added to the identity (Santos, 2002).

Aldeia Maraka’nà: A Resilient Indigenous Occupation in the Heart of Rio de Janeiro

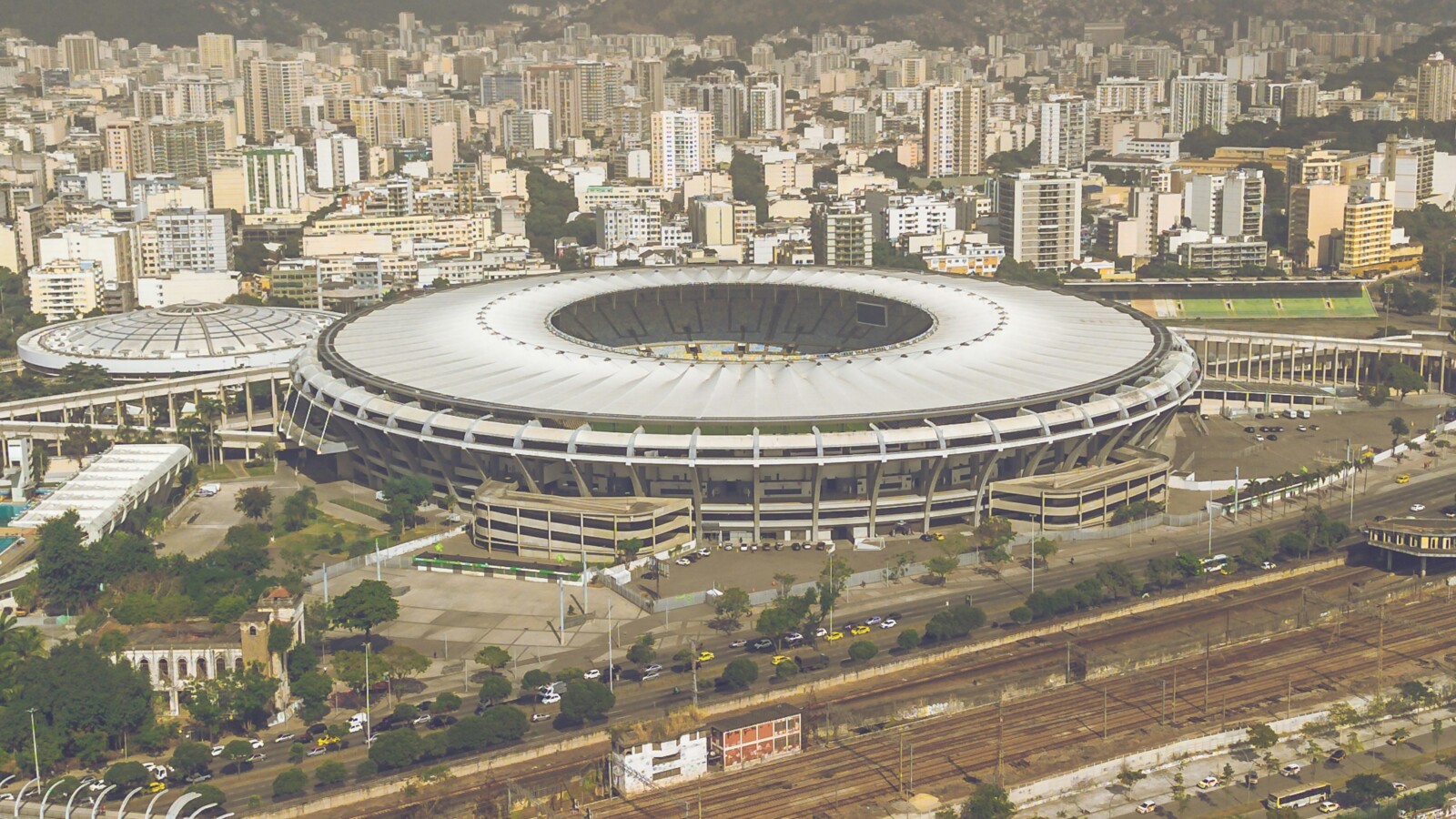

Nestled in the bustling city of Rio de Janeiro, right next to the iconic Maracanã Stadium, lies Aldeia Maraka’nà—a vibrant urban, multi-ethnic indigenous community that occupies the historic mansion once known as the “Old Indian Museum.” This unique occupation demonstrates indigenous resilience and cultural preservation in the midst of a sprawling metropolis. The name “Maraka’nà” has deep indigenous roots; it symbolises a bird whose call mimics the sound of a maraca, a traditional instrument played by shaking. This name has become synonymous with the entire surrounding neighbourhood, which is nourished by the Maracanã River that used to flows through the area.

Aldeia Maraka’nà’s journey began in October 2006, marking the start of an enduring occupation that has faced numerous challenges over the years. In 2010, the state government of Rio de Janeiro unveiled plans to demolish the mansion to make way for renovations to the adjacent Maracanã Stadium in preparation for the 2014 World Cup. These plans threatened the very existence of the occupation, leading to a tense period of uncertainty. Fast-forward to 2013, the situation escalated and police forces forcibly vacated the building, displacing the indigenous occupants. However, the community’s resolve remained unshaken. In 2017, indigenous people bravely reoccupied the mansion, reclaiming their space and continuing their fight for cultural preservation and recognition.

Struggling for resources:

Access to water has always been a critical issue for the residents of Aldeia Maraka’nà. Before the 2013 eviction, the community relied on the National Agricultural Laboratory (LANAGRO), which shared the grounds with the former Indian Museum, for essential resources like water and electricity. LANAGRO’s support was a lifeline for the indigenous occupants, enabling them to maintain their daily activities. However, the eviction and subsequent demolition of the LANAGRO unit as part of the area’s urban redevelopment plans left the community in a precarious position. When the indigenous people returned to reoccupy the mansion in 2017, they found themselves dependent on water trucks to sustain their daily needs—a stark reminder of the ongoing struggle for access to basic necessities.

Yby: the river

Water isn’t just a survival necessity; it’s also crucial for indigenous communities to maintain control over their lands. Yet, in our modern, human-centered perspective, water often gets reduced to just another natural resource—something valuable only because it benefits us. But water is more than just a resource; it’s a key player in how we experience and relate to our environment. It shapes our sense of belonging, collective identity, and social organization in ways that go beyond its practical uses.

For indigenous peoples, particularly the Tupi groups of the tropical forest, water and waterways have always been central to their lives. Rivers, for instance, were not only vital for food and transport but were also deeply woven into their cultural practices. Take the Tupinambá people of Rio de Janeiro in the 16th century—missionaries and colonizers noted their exceptional swimming and fishing skills. The piracema season, when fish spawn, was a time of celebration and festivals in their villages, highlighting the profound connection between these communities and their aquatic environment.

This characteristic of piracema being associated with festivals in the aldeia also highlights the influence that this non-human actor had on the cultural specificities of this group. In addition to the festivals associated with piracema, we could also cite as an example the Enchanted mythological creatures of rivers and bodies of water that populate the narratives of coastal Tupi groups regarding their relationship with rivers, seas, lakes, and lagoons, such as Ipupiara, Iara, and Baétata. (Prezia, 1997)

The influence is also seen in the toponyms of places, as is the case of the Maracanã region, named after the Maracanã River that bathes the entire area. Despite being a polluted river nowadays, it is possible to imagine the importance of this watercourse for the Tupi populations that inhabited the Guanabara region during the Portuguese invasion.

In this sense, the pollution of the Maracanã River is also an obstacle to the construction of collective autonomy in Aldeia Maraka’nà. The lack of access to the river as a source of food, water, and transportation, and the denial of access to the municipal water and sewage network imposed the need to purchase water from water trucks for consumption, altering the cultural specificities of ethnic groups that occupy the space. A recurring joke among them is the need to “go fishing on the Extra River”, in reference to buying fish at the nearby supermarket instead of fishing them.

Maracanã river

Recently, indigenous people decided to dig an artesian well at the site, but they doubted the potability of the water due to the proximity of polluted rivers. The channelling of the river and the disposal of sewage since the mid-19th century have contributed to the river’s pollution, yet the community’s connection to the river remains significant. It was the combination of Indigenous knowledge and the expertise of social movements related to land reform that enabled the community to tap into groundwater resources, greatly improving their living conditions. For Aldeia Maraka’nà, the turning point lies in proposing a new relationship with the river—not to pollute it any longer, but to see it as an integral part of the community, care for it, and, when possible, use it for survival, just as they do with the groundwater.

The decision to excavate the well depended on the sharing of traditional indigenous knowledge and the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST). A landless leader, during a visit to the Aldeia, stated that, given the location of the surrounding rivers and the proximity to the sea, there would be an aquifer with water not contaminated by river pollution and began the excavation. Using common excavation techniques from MST settlements, a smaller-scale but deep excavation was conducted, reaching the aquifer and confirming its potability.

After the excavation, in conversations with other indigenous leaders and through research, the indigenous people of the Aldeia Maraka’nà discovered that the type of soil that names the entire surrounding neighborhood, Tijuca, from the Tupi Ty Iuc, refers not only to mud but to a type of clay capable of forming a barrier between the polluted surface water and the deep underground aquifer. This corroborated the knowledge of the MST leader and aligned the different bodies of knowledge.

Evaporation: a drought that brings rain

The effects of climate change arising during the Anthropocene are felt most abruptly in marginalized communities. In particular, the population is affected by the effects of river pollution that mark the relationship of modern society with the non-human elements of its environment, seen as resources.

Pollution, consequent sedimentation, and reduction of the Maracanã River are obstacles to the construction of collective autonomy for Aldeia Maraka’nà. It changes the way of life and cultural specificities of groups that were once fishermen and are now forced to buy fish and sometimes water from external suppliers.

These experiences with climate change also refer to colonization, marginalization, exploitation, and forced assimilation. The changes brought about by colonization, both environmental and societal, resulted in the marginalization of these minority groups, exploitation of land and people, and involuntary assimilation of these people.

However, as Mignolo (2008) points out, the oppressive logic of coloniality also produces energy in marginalized, invisible, and expropriated peoples of distrust and reaction to domination. This energy can be expressed in different forms of resistance, more or less open to colonial logic. Some forms of resistance in Aldeia Maraka’nà include the resurgence, resumption, and revitalization of culture and traditional knowledge, as exemplified by the well excavation project. In recent years, the indigenous movement in Brazil has not only focused on regaining territory but has also been driven by the goal of recovering and strengthening ethnic identity. These movements reflect a shift in how we perceive the world. It moves away from a modern, anthropocentric view that treats the environment merely as a resource. Instead, it embraces a more relational and holistic understanding, overcoming the hierarchical separation between humanity and nature. With this, they establish other relationships with the environment that affect non-human elements and shape the collective identities of human groups. Considering the need to combat climate change to guarantee the survival of humanity as a species, this change in perspective is increasingly urgent and necessary.

The story of Aldeia Maraka’nà is thus a vivid illustration of how cultural identity can serve as a foundation for resilience in the face of climate change and environmental challenges. Despite being embedded in one of the world’s most urbanized environments, the community has retained a deep connection to their ancestral roots, particularly through their relationship with the Maracanã River. This river is not just a natural feature but a critical element of the community’s cultural and spiritual identity, symbolizing their enduring link to the land and their ancestors.

The challenges faced by this group, from the pollution of the Maracanã River to the struggle for basic resources, are emblematic of the broader impacts of climate change on marginalized communities. Yet, the community’s response to these challenges—particularly their innovative excavation of an artesian well—demonstrates the power of cultural identity as a source of resilience.

References

Barth, Fredrik. Ethnic groups and boundaries: The social organization of culture difference. Waveland Press, 1998.

Eriksen, Thomas Hylland. “The cultural contexts of ethnic differences.” Man (1991): 127-144.

Houdart, S. (2015). Humanos e não humanos na antropologia. Ilha Revista de Antropologia, 17(2), 013-029.

Mignolo, W. (2008). El pensamiento des-colonial, desprendimiento y apertura: un manifiesto. Revista Telar ISSN 1668-3633, (6), 7-38.

Prezia, B. A. G., & Dick, M. V. D. P. D. A. (1997). Os indígenas do planalto paulista: etnônimos e grupos indígenas nos relatos dos viajantes, cronistas e missionários dos séculos XVI e XVII.

Santos, M. (2002): Por uma outra globalização. Do pensamento único à consciência universal.

[1] According to Tupi cosmology, Ipupiara was a seaman who lived on the coast of Brazil. His name can be translated as “he who is in the water”.

[2] Iara or Mãe d’Água, meaning “mother of water”, seduced men and drowned them in rivers.

[3] A creature resembling a fire snake that appeared on beaches at night. Its name can be translated as “fire thing”