Nowadays, we can rely on GPS receivers or magnetic compasses to tell us how to reach our destination. Some 1000 years ago, Vikings had none of these advanced navigation tools. Yet, they successfully sailed from Scandinavia to America in near-polar regions where it can be hard to use the Sun and the stars as a compass. Clouds or fog and the long twilights characteristic of polar summers complicate direct observations of these celestial bodies. So how did they find their bearings? A new study published in Proceeding of Royal Society A shows that they probably used Iceland spar, a “sunstone”.

Centuries-old Viking legends tell of glowing sunstones that navigators used to find the position of the Sun and set the ship’s course even on cloudy days. In 1967, a Danish archaeologist named Thorkild Ramskou speculated that the Viking sunstone could have been Iceland spar, a clear variety of calcite common in Iceland and parts of Scandinavia.

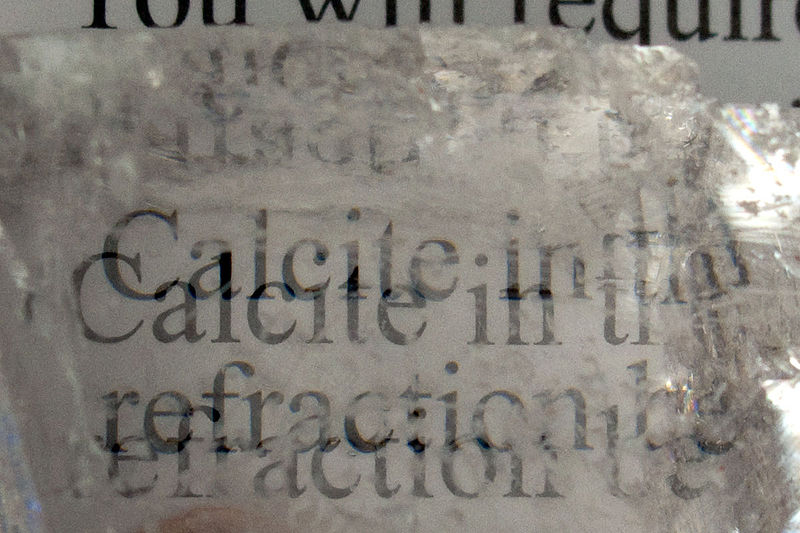

This crystal has an interesting property called birefringence: a light ray falling on calcite will be divided in two, forming a double image on its far side. (This double image is easily seen by placing transparent calcite on printed text.) Further, the Iceland spar is a polarising crystal, meaning the two images will have different brightnesses depending on the polarisation of light.

Birefringence of Iceland Spar seen by placing it upon a paper with written text. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Light is made up of electromagnetic waves with component electric and magnetic fields. If these components have a specific orientation, the light is said to be polarised, while in unpolarised light the orientation of these fields has no preferred direction. Calcite can appear dark or light depending on the polarisation of light that falls upon it.

Sunlight becomes polarised as it crosses the Earth’s atmosphere, and the sky forms a pattern of rings of polarised light centred on the Sun. Changing the orientation of calcite as light passes through it will change the relative brightness of the projections of the split beams, even when the Sun is hiding behind clouds or just below the horizon. The beams are equally bright when the crystal is aligned to the Sun.

It can be hard to determine when exactly these split beams have equal brightness. But the new study, led by Guy Ropars at the University of Rennes 1 in France, suggests Vikings could have built a simple device to better use the sunstone.

The technique consists in covering the Iceland spar with an opaque screen with a small hole in its centre and a pointer. As light passes through the hole onto the crystal, a dark surface below it receives the projection of the double image for comparison.

The authors of the Proceedings of the Royal Society study believe Vikings could have used a device like this to navigate. The crystal is inside, and the projection of a double image is seen below it. Credit: Guy Ropars. Source: ScienceNOW.

By rotating the apparatus and determining the direction at which the two images were equal in brightness, the team managed to pinpoint the Sun’s position on a cloudy day with an accuracy of one degree on either side. Researchers also conducted tests when the Sun was largely below the horizon. “We have verified that the human eye can reliably guess clearly the Sun direction in dark twilights, even until the stars become observable,” Ropars’ team writes in the paper.

Although archaeologists have not yet found Iceland spar among Viking shipwrecks, the new study adds credence to the idea that Viking seafarers used the crystal in their travels.

Further, the recent finding of a calcite crystal on a sixteenth century Elizabethan ship shows that navigators could have used Iceland spar even after the appearance of the magnetic compass. Cannons on ships could perturb a magnetic compass orientation by 90 degrees, so a crystal serving as an optical compass could be crucial in avoiding navigational errors and get sailors to a safe port.

By Bárbara Ferreira, EGU’s Media and Communications Officer

Pingback: The Stunning Geology Of Iceland - NewsProPlus.com

Pingback: 6 creencias antiguas y extrañas con explicaciones lógicas | Marcianitos Verdes

Eygló Aradóttir

“Centuries-old Viking legends tell of glowing sunstones that navigators used to find the position of the Sun and set the ship’s course even on cloudy days. In 1967, a Danish archaeologist named Thorkild Ramskou speculated that the Viking sunstone could have been Iceland spar, a clear variety of calcite common in Iceland and parts of Scandinavia.” My brother and I got into discussion on if there are some older documentations of vikings´use of sunstone or if this is a later time explanation on their travelling.

Lee Waterworth

K

Pingback: GeoLog | This calls for a celebration: GeoLog’s 1000 post!

Chris Callaghan

I am preparing a presentation arguing that the Neolithic monument at Newgrange, Co Meath, Ireland is not a tomb or passage grave, but a Fertility Temple. Of the two blocks used by the Neolithic sun-worshippers, the one apparently of quartz was found by Michael O’Kelly in 1967, but has subsequently disappeared. Its twin was missing when O’Kelly cleared what he called the roof-box. I have re-named the Neolithic app., the sun window. I suspect the quartz block was used by the ancients to diffuse the Winter Solstice sunlight into its rainbow components, while the second block was Iceland Spar, or calcite. This block told the “priests” when the sun had risen during Ireland’s often cloudy weather. Thus allowing the Fertility celebration to begin.

Comment will be much appreciated. Thank you.

KL

That is fascinating Chris! I would have loved to have seen your presentation and to learn more about the temple. Thank you for letting us know about it here!