Congratulations on receiving the 2024 Hannes Alfvén Medal for your pioneering work and outstanding leadership in advancing our understanding of space plasma physics, including its fundamental processes and impacts throughout the solar system and beyond. What does this recognition mean to you personally, and how does it impact your work in this fascinating field?

I am deeply honoured to be awarded the Alfven Medal. I work on a number of things with the overall aim of finding (a) something that is beautiful and (b) something that is useful. I think that space physics has scope not only to provide useful things—such as a quantitative understanding of space weather risk—but also can contribute to some of the outstanding questions in physics. Making progress requires trying out new ideas and taking risks, and recognition by the Alfven medal is a recognition of that.

I work on a number of things with the overall aim of finding (a) something that is beautiful and (b) something that is useful.

The only other woman to receive the Alfven Medal was Margie Kivelson in 2005. At the very outset of my career, as a young grad student and then postdoc, I would go to meetings and workshops and Margie would be the only other woman there! Margie was always very friendly and supportive, and seeing her contribute to science was a real inspiration for me.

The only other woman to receive the Alfven Medal was Margie Kivelson … seeing her contribute to science was a real inspiration for me.

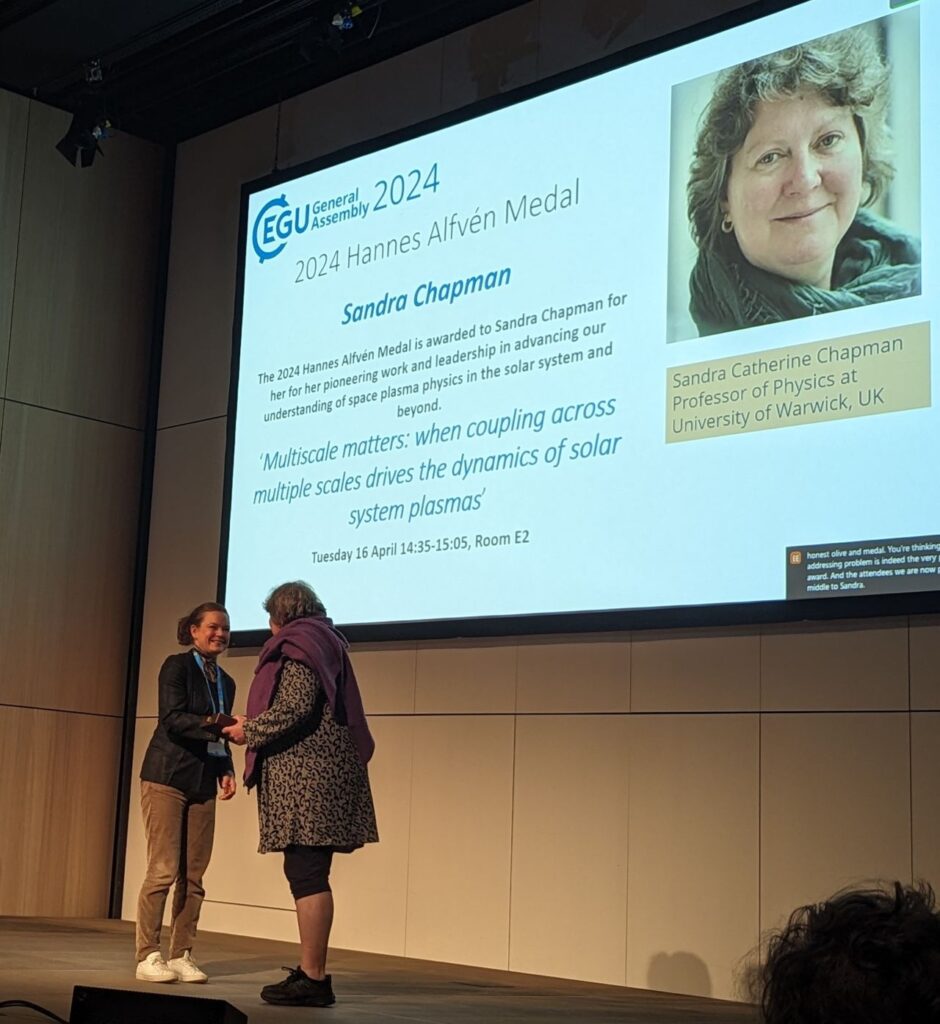

Sandra Catherine Chapman accepts her medal at the EGU24 General Assembly in Vienna, Austria. (Credit: University of Warwick)

Could you share some information about your background and what sparked your interest in your research field?

I always wanted to do science. I was inspired by the moon landings for sure, but also, I have a deep need to understand the nature of things. I also am very visual in my thinking, I like making art, both 2 and 3D. A lot of the swirling shapes of my vases and bowls are inspired by plasma physics. So, when deciding what science to do, electrodynamics, plasmas, and nonlinear physics were the natural choices.

Could you tell us some of the key challenges you have encountered in your scientific career, and how have you navigated them?

I think the general problem is always the lack of funding to have fun and take risks. Nearly all of the work I’ve done that has made an impact was not directly supported by standard research grants. The exception has been personal Fellowships, which I have benefited from greatly—thank you, funders!

Like many, I have also worked while managing health issues. For much of my early career, I was impacted by epilepsy, and more recently, I have survived breast cancer—twice. My approach has always been to keep doing some physics, if nothing else, to have conversations with people other than medics!

Your research expertise is exceptionally diverse and wide-ranging. Could you share a brief overview of the key discoveries or milestones that have shaped your career and brought you to this point?

Which is the most important for the milestone: the chisel or the sculpture? For me, it has been an appreciation of the connections between plasma and statistical physics. These connections have led me to bring new ideas and methods to the study of space plasmas. The unsolved problem of matter far from equilibrium is the problem of how a collisionless plasma increases entropy, which is the problem of how turbulence, reconnection and collisionless shocks work. That is needed to understand things like how the solar wind is heated, how particles are accelerated to high energies, and so on.

Which is the most important for the milestone: the chisel or the sculpture?

How do you foresee your research evolving over the next 3-7 years, and what key challenges or opportunities do you anticipate?

I think these are both exciting and challenging times. For my work, it is exciting as we now have the opportunity to access many large, well-curated datasets from in-situ spacecraft, ranging from close to the sun to Earth, and an Earth well-instrumented in terms of ionosphere and ground impacts. We need to implement new ways to utilize these rich and diverse datasets, and there is a lot that we can borrow from other research fields where network science and statistical methods are more mature. Upcoming multi-spacecraft missions will be a game-changer for understanding turbulence and other non-linear phenomena in space.

We now have the opportunity to access many large, well-curated datasets … We need to implement new ways to utilize … and there is a lot that we can borrow from other research fields where network science and statistical methods are more mature.

It is challenging, as some scientists are facing restrictions and funding cuts at the very moment when we need to combine all our expertise and resources to face global challenges. Science is truly international, and we will all have our part to play in keeping our conversations about science free and open to all.

How do you manage the demands of your research alongside personal life and other commitments, and what strategies have you found most effective in maintaining a healthy balance?

My life has been a worked exercise in ‘work-life balance’. My advice, the usual things, find some exercise that you love, eat food that is kind to your body, but also accept that sometimes life will throw some big obstacles in your path, this is normal, and if you let them know what is happening, colleagues will support you and you can have a full and rewarding career. I also find that doing something completely different, in my case, painting and ceramics can help let the new ideas come out.

My life has been a worked exercise in ‘work-life balance’.

In your experience, what are the most pressing scientific questions in your field, which ones are likely to be solved soon, and why do you believe they hold such urgency?

How does entropy increase in a collisionless plasma? Can algorithms—machine learning, networks, AI—find patterns in the data that lead to new physical insights? The first question won’t be solved anytime soon, but it is a worthy adversary of a problem. The second one is urgent—we need to understand and master these new approaches—otherwise, we will end up with epicycles instead of orbits determined by the law of gravity.

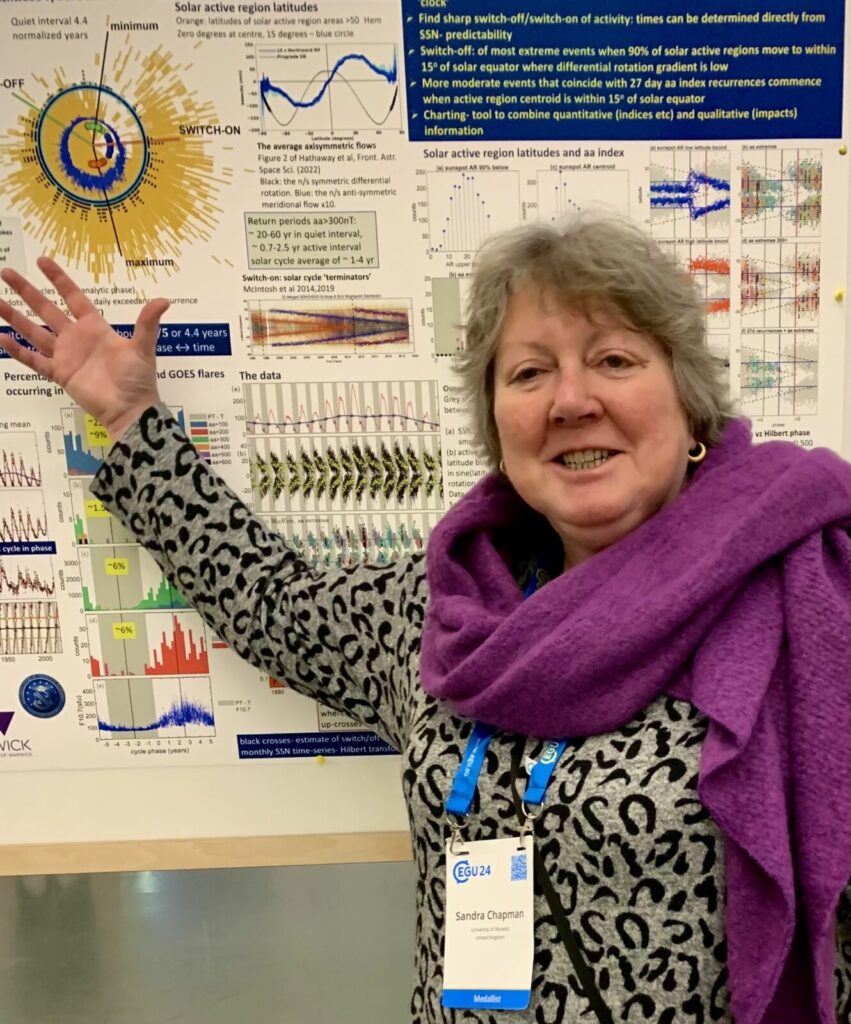

Sandra Chapman highlighting a regular clock for the solar cycle variation of sunspot and geomagnetic activity at the EGU24 General Assembly in Vienna, Austria.

What advice would you give to Early Career Scientists seeking to succeed in this field, and is there a particular skill or mindset you believe is crucial for success in solar-terrestrial research?

If you want something that is a lifelong passion rather than a day-job, then ‘follow your heart’. Don’t be afraid to go for highly competitive opportunities, like Fellowships, that allow more academic freedom, and don’t be put off by rejection, there simply isn’t enough funding to go around for all the great ideas people have. Do extract from reviews of your work anything useful to help you improve it—if the reviewer doesn’t understand your paper, no matter how grumpy they may be—then it could probably do with some clarification. Finally, do travel, and collaborate—learning, sharing and growing new ideas with others is a major perk of the scientific life.

If you want something that is a lifelong passion … ‘follow your heart’… and don’t be put off by rejection.