There is something about really BIG things that always grabs people’s attention – look at dinosaurs for example. The geological record is littered with the extreme and today we will explore the biggest, the tallest, the deepest and steepest sedimentary structures and landforms ever to grace our planet. Depositional environments ranging from fluvio-lacustrine and aeolian, coastal environments and a range of marine settings have been studied to identify the record breaking dunes, bars, channels, deltas, sheet sands, canyons and more. Every example discussed is depositional rather than simply geographical, so no mountains but plenty of sand and a little limestone.

Each “giant in its field” is then compared to the largest modern example to get a sense for just how different ancient environments were when stacked up against their recent counterparts. Obviously, we are missing some ancient examples due to erosion through time, but with what remains, will there be more ancient examples or modern ones? Read on and find out. We will also examine which time periods favoured the biggest ever sedimentary landforms and consider what global cycles might be responsible.

Titanic terrestrial settings

Our journey begins in the foothills, seeking the largest braid plain. Back in the Precambrian, rivers were unconstrained by vegetation leading to some enormous braid plains. The most valuable, covering a third of South Africa, fills the Witwatersrand Basin with gold bearing conglomerates. However, this example is dwarfed by the largest modern braid plain flanking the Brahmaputra River, estimated to cover more than 650,000 km2 (Fig 1), although parts of it are more meandering. While we are on meandering rivers, have you ever wondered what is the thickest point bar? The Amazon River drains 7 million km2 and reaches 100 m water depth, with point bar deposits up to 38 m in thickness. However, Alberta’s McMurray Formation (Fig 2) has individual packets of inclined heterolithic stratification up to 58 m thick, deposited by a truly gargantuan river system that may have originated in the Mississippi region, draining the north American continent.

- Figure 1 Braid plains of the Brahmaputra, India

- Figure 2 A point bar in the McMurray Oil Sands, Fort MacMurray, Alberta

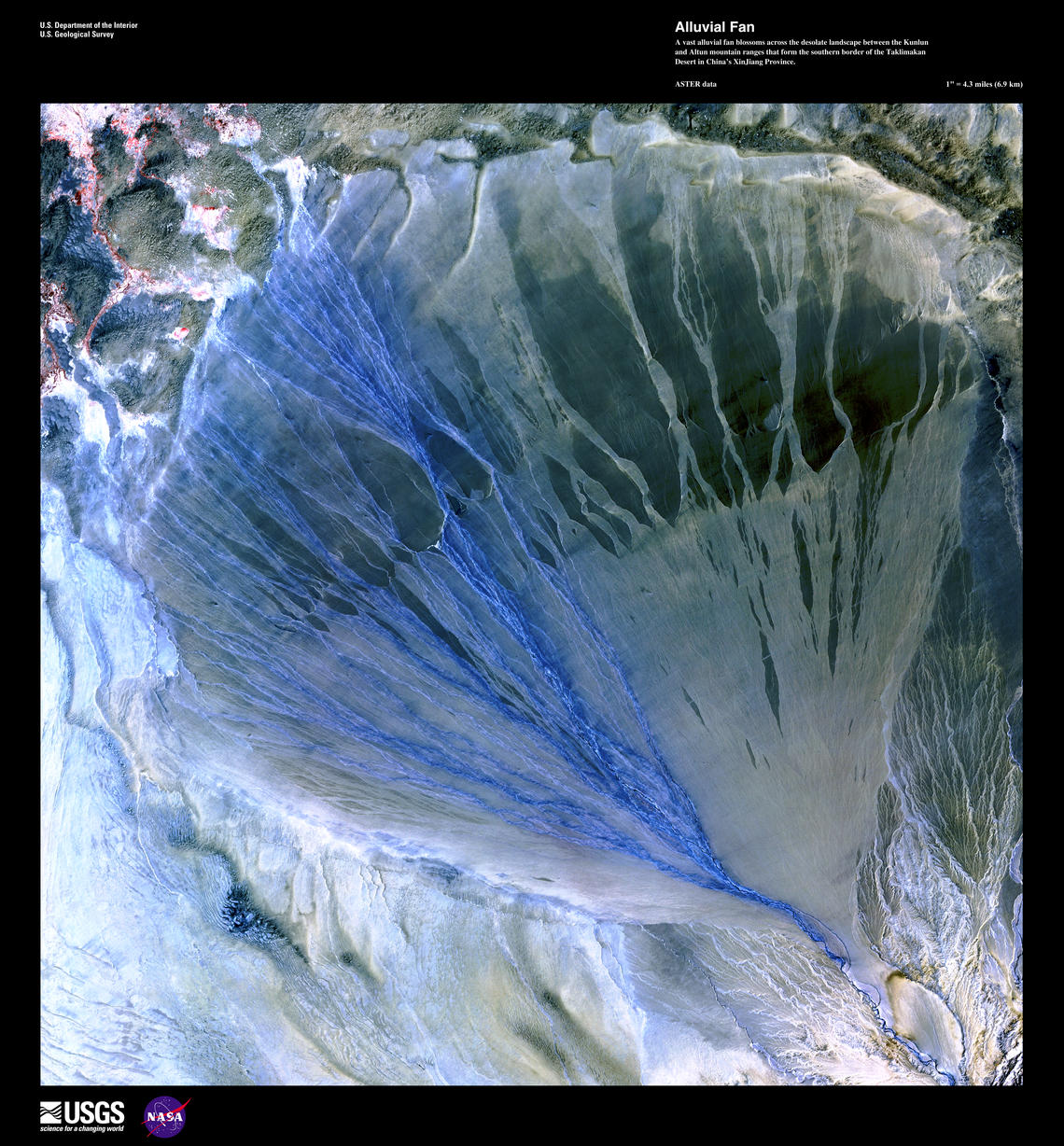

Separating alluvial fans from distributive fluvial systems (DFS) can be challenging. The Taklimakan Fan in China (Fig 3), 61 km in length, is the world’s largest alluvial fan at 3477 km2, while the much larger Kosi Megafan (15000 m2) is considered to be a DFS. Preservation potential of ancient alluvial fans is fairly low, as they are often related to tectonic active regions, and potentially the largest known in the fossil record are the Triassic fans of southern Devon, significantly smaller at around 30 km in length, feeding material from uplifted massifs.

When investigating huge landforms, there are some givens. Everyone knows that the largest sand dunes are in Namibia, right? Dune 7 is 383 m tall (Fig 4) which is only a quarter of the height of the Duna Federico Kirbus, adjacent to a mountain range in Argentina (1230 m tall). Obviously these dunes are composite, but they comfortably outweigh the stunning red, aeolian sediments of the southern US. The entire Wingate Formation is only 609 m thick but probably had some enormous dunes developed in the arid interior of Pangaea. Preservation potential for desert deposits is usually very poor.

Where is the largest lake? Lake Baikal is larger by volume, 23,013 km3, containing 20% of Earth’s fresh surface water. The Caspian Sea has a greater surface area, around 370,886 km2, and Lake Chad is only slightly smaller, though mostly dried up now. Fortunately, the Pleistocene Lake Agassiz of Canada and the US (Fig 5), a proglacial lake formed by meltwater and dammed by ice, comfortably outdoes both. It covered around 440,000 km2, an area larger than all the Great Lakes combined. When it drained, it created an estimated 2.8 m rise in global sea levels. The world’s largest ever flood originated in the same region, at roughly the same time, when Lake Missoula washed away its ice dams with flows up to 386 million m3/second. It flooded more than 44,700 km2 of terrain, almost double the area in Bangladesh, where up to 26,000 km2 is flooded most years. The flow was strong enough to carve giant ripples into the landscape (Fig 6).

- Figure 5 Pleistocene Lake Agassiz of Canada and the US

- Figure 6 Giant ripples created by Lake Missolua

Finally in this section, the world’s largest waterfall is the Angel Falls in Venezuela, plunging 807 m with a discharge of 16990 m3/second. While ancient waterfall deposits have a very low preservation potential, we know that sea level rise in the Upper Miocene, following the Messinian Salinity Crisis, created a waterfall that filled the Mediterranean in less than 2 years (Fig 7). The slope of the Falls was probably gentle, but the drop was 1500 m with an estimated peak discharge of over 100,000,000 m3/second, carving a 250 km long channel through the Straits. If you had a time machine, this would surely be one of the world’s greatest ever sights.

Coastal Colossi

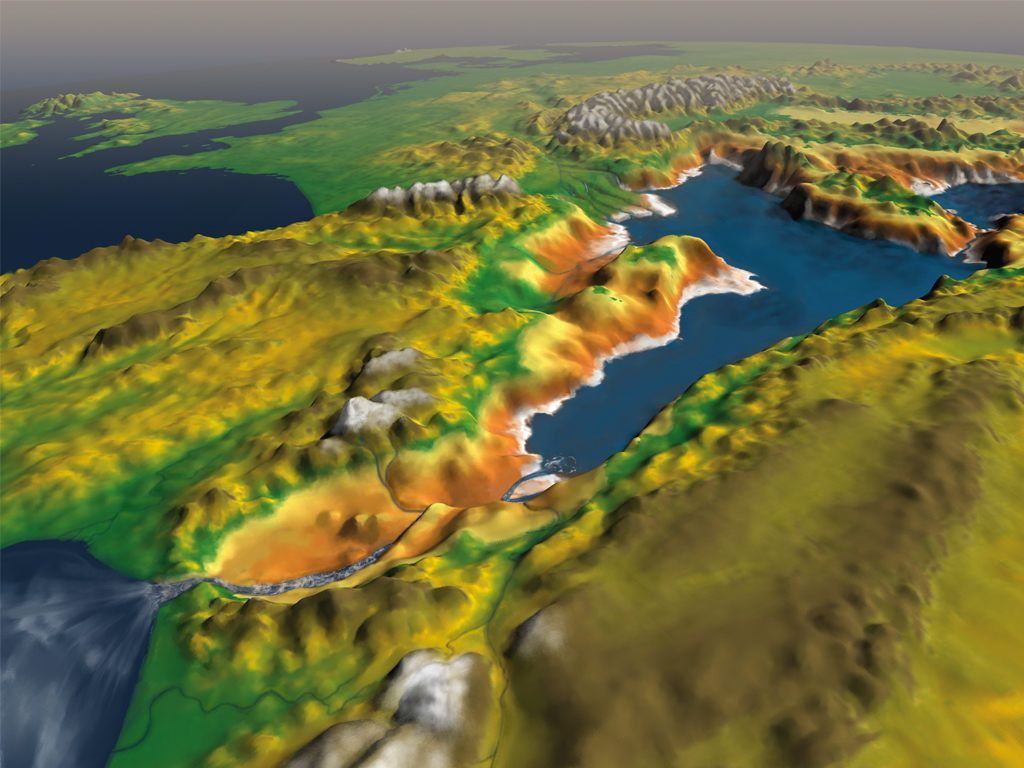

We have already mentioned the Cretaceous McMurray Formation. A giant river should have a giant estuary, which for simplicity includes its incised valleys, giving a 300 km long basin with palaeo drainage extending throughout. Preservation potential is high in such settings, as estuaries usually form due to sea level rise, which eventually caps them with marine sediments. Turning to modern estuaries, facilitated by Holocene sea level rise, the Gulf of St. Lawrence in Canada has an estuarine channel (Fig 8) that is 1197 km long, with its Gulf covering 226,000 km2. A worthy champion.

In contrast, fossil mangroves are considered to have low potential for fossilization. The Miocene Santanyi Formation of Mallorca covers around 50 km2, similar to the Purbeck Limestone, while the largest ancient deposits may be associated with the Eocene London Clay and its Nipa fruits, with the entire Formation covering around 10,400 km2, of which perhaps 10% were mangroves. This is much smaller than the mighty Sundarbans of Bangladesh and India (Fig 9), at around 10,000 km2.

- Figure 9 Mangroves of the Sundarbans of Bangladesh and India

- Figure 10 Middle Triassic Boreal Ocean Delta

- Figure 11 Cadaley-Dhimbii coast in Somalia

The Ganges Delta is associated with both the Sundarbans and the largest braid plain, and is the world’s largest delta at 105,000 km2, but is simply outclassed by the little known Middle Triassic Boreal Ocean Delta. It covers 1,650,000 km2, around 1% of the Earth’s surface (Fig 10) and drained northern Pangaea. Meanwhile the longest continuous beach is trumpeted across the internet as Praia do Cassino Beach, Brazil, at 254 km, but this is half the length of Swakopmund Beach in Namibia, and only a third the length of the Cadaley-Dhimbii coast in Somalia (Fig 11: 700 km long and 910 km to drive). Limited preservation potential probably explains why the longest beach in the fossil record, from the Permian Waterford Formation of South Africa, is only around 90 km in length. I suspect that much longer beaches occurred in both the Western Epicontinental Seaway and in the Book Cliffs region.

Marine behemoths

The next category is difficult to define, the longest shoreface. I used a world seabed sediment map to find the longest expanse of sand, offshore Argentina, which may be continuous. However, the Cambrian Gog Quartzite of Alberta stretches for an estimated 2300 km. The Okotoks Erratic in Alberta (Figure 12) is made of this quartzite.

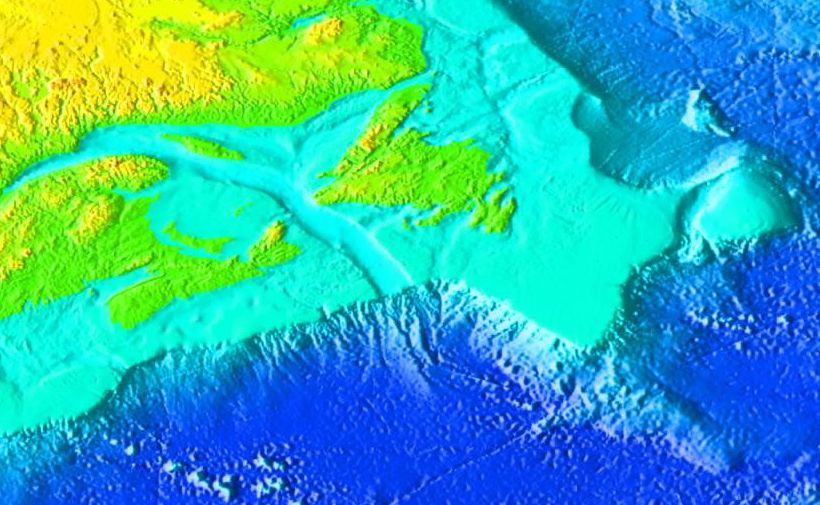

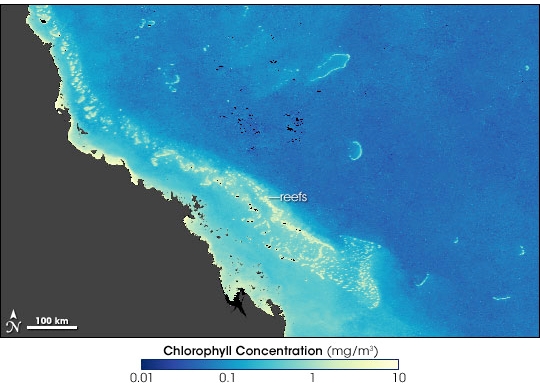

Our only carbonate is invoked for the biggest reef. The Middle Devonian Canning Basin covers 17,500 km2, but there may be much bigger Jurassic and Cretaceous reefs in the Middle East. The Great Barrier Reef of Australia, covering an area of 344,000 km2, is very difficult to beat for size (Fig 13), as potentially gigantic Carboniferous reefs have, for the most part, been eroded away.

- Figure 14 Fraser Island, the world’s largest barrier island

- Figure 15 NAMOC submarine canyon

The biggest barrier island, Fraser Island (Fig 14), lies off the coast of Australia. The largest sand island in the world, it has an area of 2700 km2, a mere bagatelle when compared to the Cretaceous Hoadley Gas field of Alberta, with an area of 3,885 km2. The field holds an estimated 6 to 7 Tcf of gas. Finally, the world’s longest submarine canyon is the NAMOC (Northwest Atlantic Mid-Ocean Channel) canyon (Fig 15), which is up to 7.5 km wide and 3800 km in length. The longest ancient canyon that I could find was offshore Louisiana, where an unnamed canyon in the Paleocene Wilcox Formation reaches around 90 km.

Discussion and conclusions

The Giants are sprinkled fairly evenly around the globe (Fig 16: modern giants in yellow; ancient giants in orange), although there are two areas where more are concentrated. Modern giants are located around the Ganges Delta, while many Cretaceous landforms are situated in north America. It is likely that several better options are located elsewhere on the map, as the examples chosen were limited by the research capabilities of the author. Technically, to undertake a thorough survey of these structures would involve reading every paper ever written on every depositional setting – a mammoth task indeed, and we are only scratching the surface with this article: there are at least one hundred different landforms that I could have included.

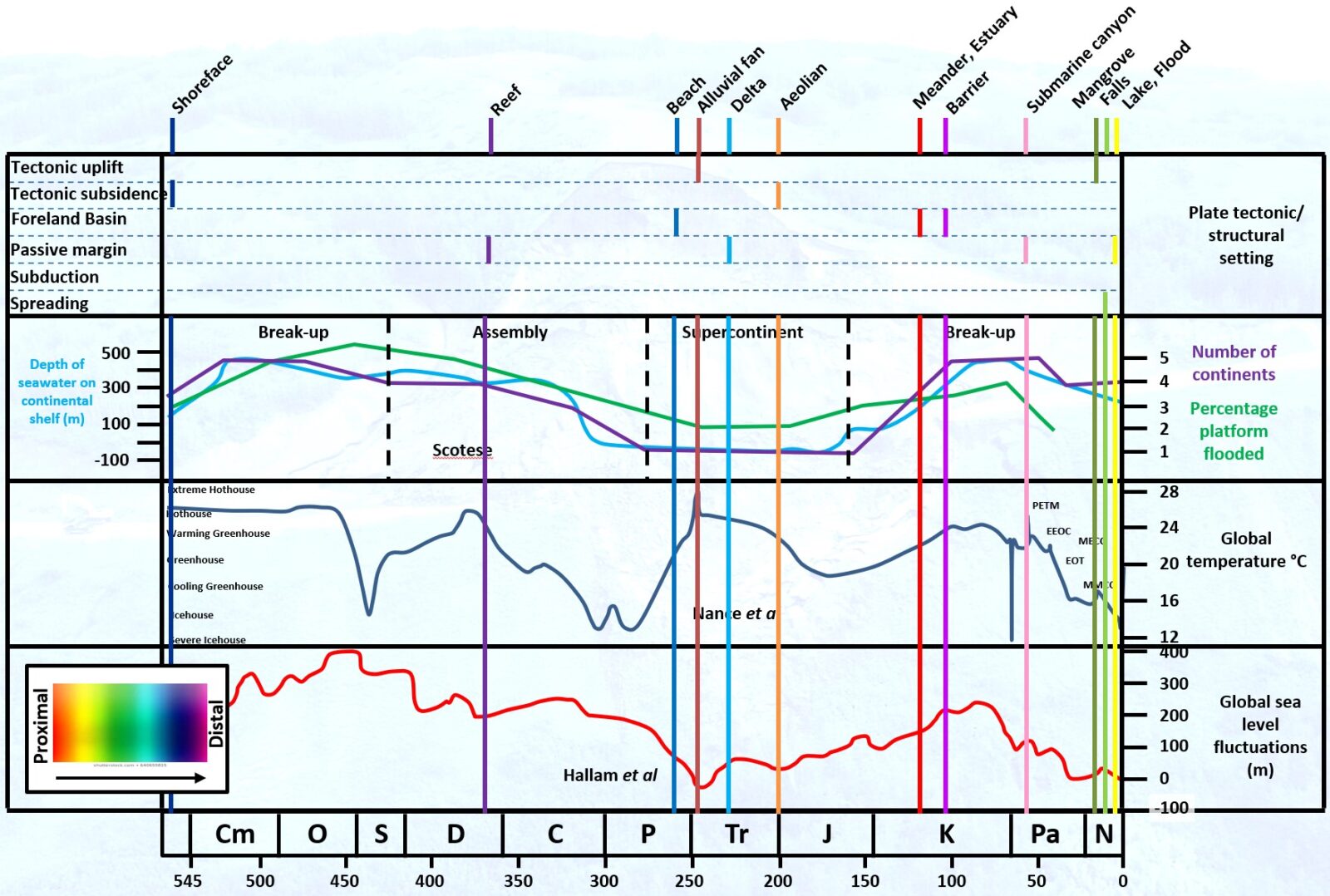

A summary chart for ancient giants (Fig 17) shows several global cycles including Plate Tectonic settings; Number of extant Continents; Global Temperature and Global Sea Level through time. Against this I have plotted the ancient giants from each depositional setting (the settings are colour coded from proximal to distal). There is a cluster in the Triassic, no doubt related to the formation of Pangaea; and a second in the Neogene, affected by the Ice Ages. It seems that global temperature extremes are the major driver in the creation of the sedimentary giants.

Counting up the results, we have SEVEN ancient giants and EIGHT modern giants. Clearly this is an example of preservation bias at work, as it seems very unlikely, to paraphrase Walther, that “the present is more extreme than the past”. I hope to look at more examples from the ancient record and welcome suggestions for more candidates. I would also like to expand to look at the largest bedforms, such as trough cross-beds, ripples, flutes, sand waves and more. Defining these features will probably be even more challenging than it was for the giant landforms. Meanwhile look out for the next Christmas best seller: the Guinness Book of World Sedimentary Records!

References

Figure 1 https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/147591/the-braided-brahmaputra

Figure 2 Author’s image

Figure 3 https://www.usgs.gov/media/images/alluvial-fan

Figure 4 Dune 45: Wikipedia

Figure 5 Lake Agassiz – Wikipedia

Figure 6 https://hugefloods.com/3-Camas-Prairie.html

Figure 7 http://retosterricolas.blogspot.com/2009/12/inundacion-catastrofica-de-un.html

Figure 8 Laurentian Channel – Wikipedia

Figure 9 https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/7028/sundarbans-bangladesh

Figure 10 https://doi.org/10.1130/G45507.1

Figure 11 Adale Youth Development Organization – AYDO (Facebook)

Figure 12 Author’s image

Figure 13 Great Barrier Reef – Wikipedia

Figure 14 https://whc.unesco.org/en/documents/119885

Figure 15 Northwest Atlantic Mid-Ocean Channel – Wikipedia

Figure 16 Author’s image

Figure 17 Author’s image

Please note:

Much of this data was originally presented at BSRG 2019 and at Geoconvention 2020.