This article aims to gather support from public or private organizations and individuals so we can convince the Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources and the National Commission of Natural Protected Areas of Mexico to protect the area that covers El Gordo Diapir in Nuevo Leon, Mexico (https://www.gob.mx/conanp/). There is no intention to damage the image of any company that might have an interest in exploiting the natural resources of El Gordo Diapir, but to debate whether this and other similar case studies should be protected by national offices responsible for environmental protection of natural areas.

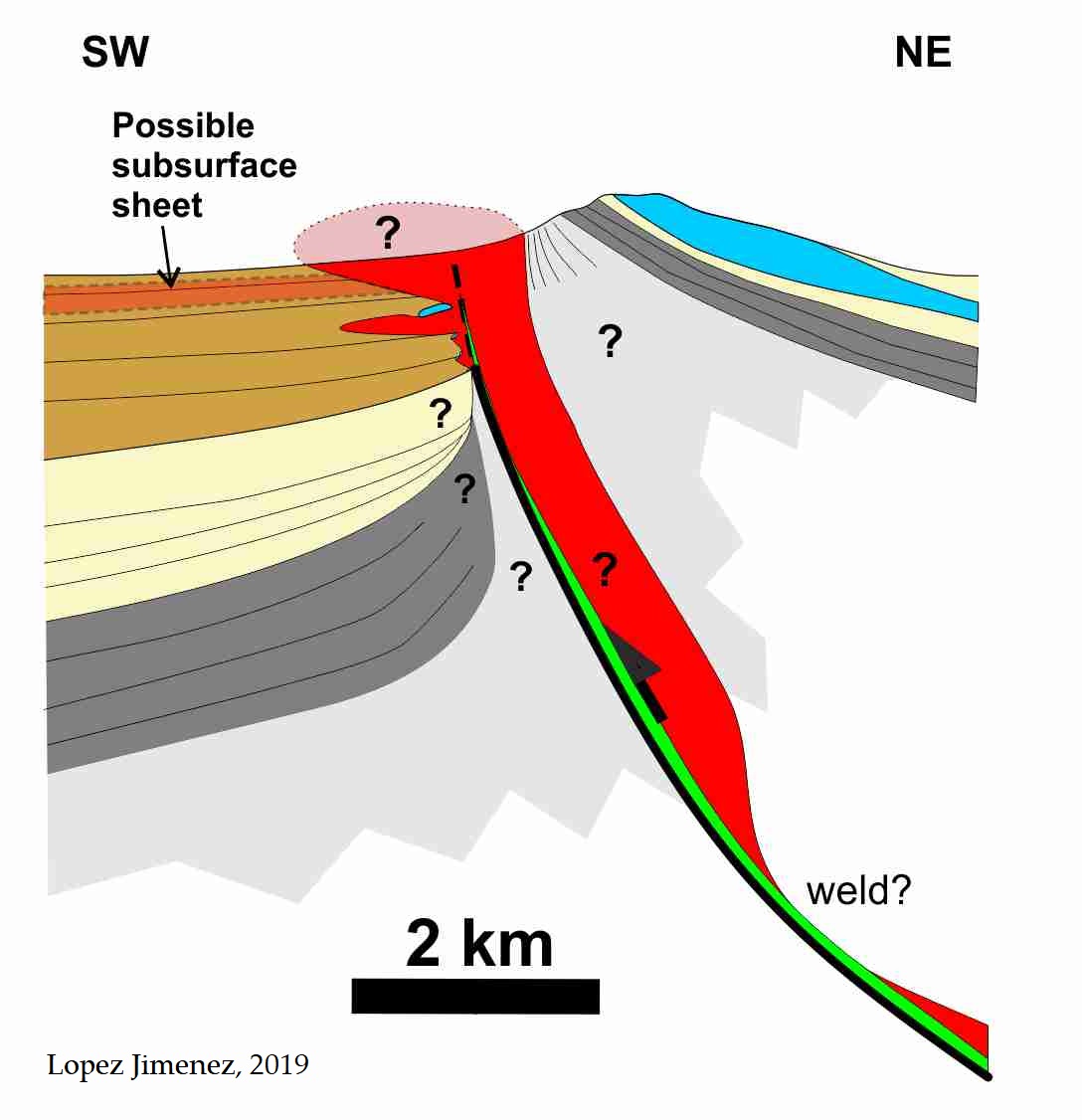

Nations tap into natural resources to keep their/our societies thriving. However, when doing so, we typically modify the environment. Mining, especially open-pit mining, is highly destructive as it removes vast areas of the Earth’s surface. Geologists typically learn from rock exposures, also known as outcrops, about Earth’s history. This includes processes that happen today and others that have happened in the past. The knowledge extracted from the study of outcrops has allowed humanity to prosper. Some areas contain world-class outcrops that exceptionally expose stratigraphic sequences where we can learn about key processes that affect us all, such as the current global climatic change. El Gordo Diapir is a geological structure that comprises a mass of salt and a series of sedimentary and igneous rocks that both rim and interbed the salt. The salt rose through the Earth’s crust from a massive regional accumulation originally deposited during the Jurassic period (see Figure 1). The arid character of today’s regional climate and the complex folding of the crust in this area of Nuevo Leon, Mexico, enable the observation of continuous exposures of the salt mass “anatomy” and the sedimentary units deformed by both the salt movement and regional tectonics. This is probably the best place on Earth where people can easily go to observe a salt diapir case study. These high-quality observations can help current efforts in the scientific community to successfully design Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS) projects (read about this topic here: https://www.iea.org/reports/about-ccus, https://netl.doe.gov/carbon-management/carbon-storage/faqs/carbon-storage-faqs, https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2021-04/Geologic%20CO2%20storage%20report_final_EN.pdf).

Figure 1. The first hundred meters of the El Gordo subsurface can be reconstructed thanks to the complex folding in the area.

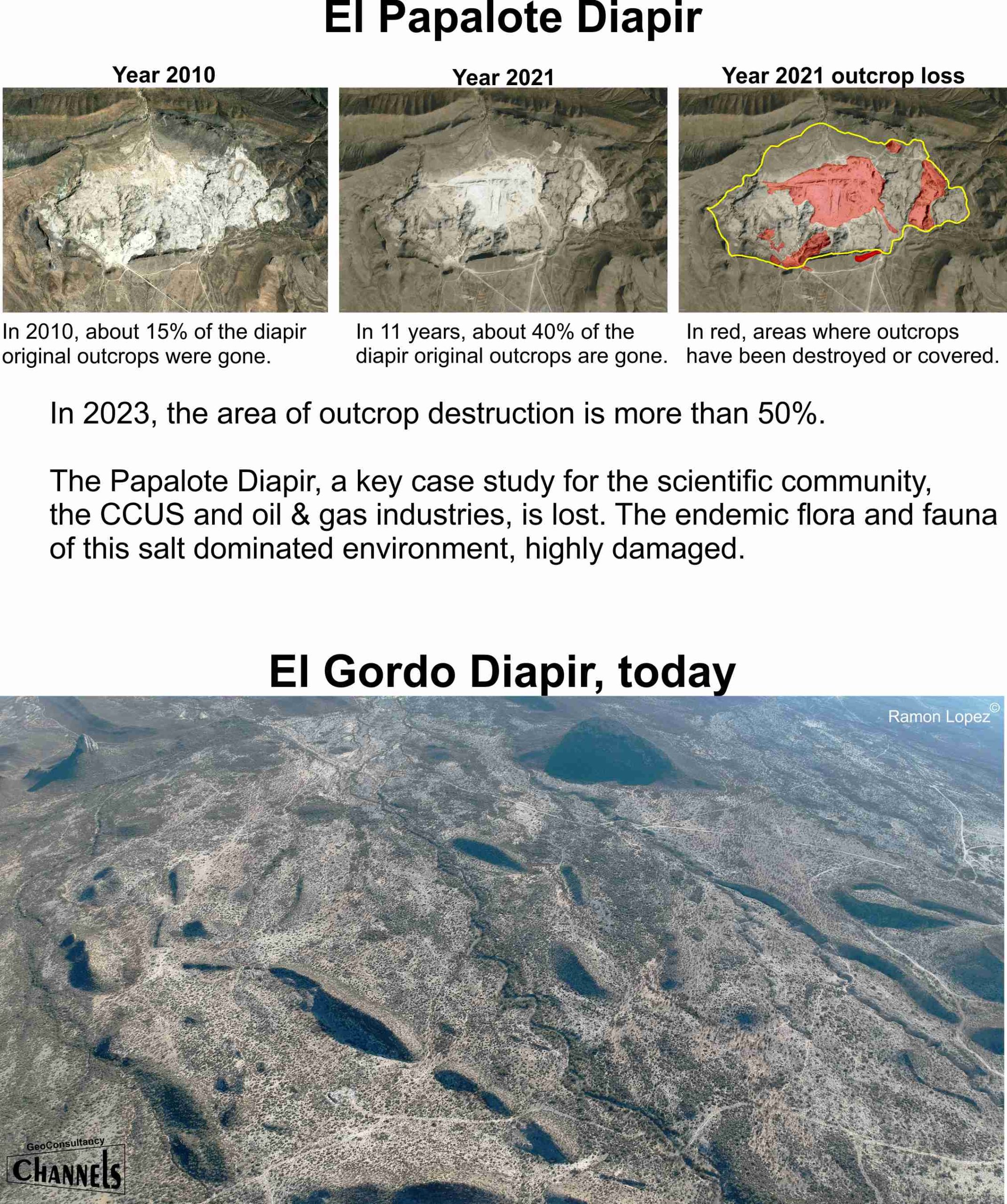

There is another salt diapir exposed a few kilometers to the north of El Gordo Diapir, called the Papalote Diapir. This was another unique and exceptional case study of a diapir that evolved in a complex tectonic setting, concluding with a compression from the propagation of a fold and thrust belt. It ‘was’, because open-pit mining destroyed a large part of the diapir exposures, and those that are preserved are not accessible due to nearby mining operations. There was not enough time for geologists to study in detail the outcrops of El Papalote, leaving many questions about the mechanics of salt movement and the consequences on the deformation of surrounding rock formations unanswered. The damage is done in the El Papalote diapir, and now inhabitants around El Gordo Diapir confirm that mining companies are close to obtaining permission from the Mexican Government to start operating in El Gordo Diapir. In Figure 2 the increasing damage in the El Papalote diapir is clear as well as the current pristine condition of the El Gordo exposures.

Do you think that mining is a priority in this case, or should this site be protected so that today’s and future generations of scientists have the opportunity to improve our understanding of how salt flows inside the Earth? If you want to support our initiative to seek protection for El Gordo Diapir, please get in touch with us at r.lopez.jimenez00@aberdeen.ac.uk. We are looking for advice to define the best strategy to convince the Mexican government to protect El Gordo.

Jon Noad

Great article! I think that preservation of our geological heritage is important for so many reasons:

– as a potential resource to help scientists understand the subsurface

– as a geological teaching resource

– to enable future generations to enjoy geological wonders

– to preserve potentially unique environmental settings

and much more.

Here in Alberta, we have the Historical Resources Act, created in 1973, which provides for the use, designation and protection of historic resources, including palaeontological, archaeological, historic or natural sites, structures or objects. Hopefully other countries will adopt a similar framework.

Ramon Lopez

Thank Jon! Totally agree. I will take a look to the Canadian Act and see if I can suggest it as a frame of reference to Mexican authorities.