INTRODUCTION

Shows involving homicides and associated crime scene investigation (CSI) are among the most popular on television. The public is fascinated by the work that goes into collecting and analysing data from crime scenes in the field (Figure 1), whether it be DNA, wounds and bloodstains, footprints, tire tracks, or even evidence of arson. Skeletal analysis can provide a detailed profile, and even a life history, of the victim, and there is almost always a method to estimate time of death (TOD).

As sedimentary geologists, our fieldwork has very similar objectives: using data from the “scene” to estimate depositional setting, flow velocities and water depth, and the nature of deposition. Grain size, sedimentary structures, bed thicknesses, sediment colour and composition, provenance and,

most importantly, context allow us to build a picture of the “scene” at the time of deposition. Palaeontological data can tell us a great deal about our “victims” (AKA fossils), while trace fossils record organism behaviour, sometimes immediately prior to death. Stratigraphy, index fossils, and correlation can be used to determine TOD (time of death or deposition).

Entire university courses focus on forensic science, and I believe there is much that the geologist could learn from techniques utilized by crime scene investigators—and vice versa. Some concepts that are potentially useful to geos are highlighted below.

THE CASE…

A young dinosaur has met its end, but beyond that, little is known. Who was this dinosaur? How old was it? How did it die? The boxes presented through this article track and interpret the (geological) forensic evidence used to solve this unexplained death.

————————————————————————————————————————————-

EGU Case File DINO 7oo1

1. THE CRIME SCENE

• Samples collected to assess grain size

• Sedimentary structures recorded to

understand setting

• Search for trace evidence (footprints, etc.)

• Associated remains analyzed

• Pollen collected

————————————————————————————————————————————-

WORKFLOW

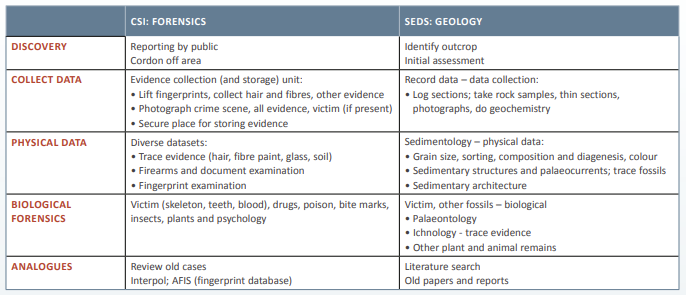

Both forensics and sedimentary geology have well-established workflows to identify cases and collect and interpret data relating to crimes or geological puzzles (Table 1). Data collection is key and should not be influenced by theories regarding what happened. The use of analogue data is often critical to making correct interpretations.

TOOLS OF THE TRADE

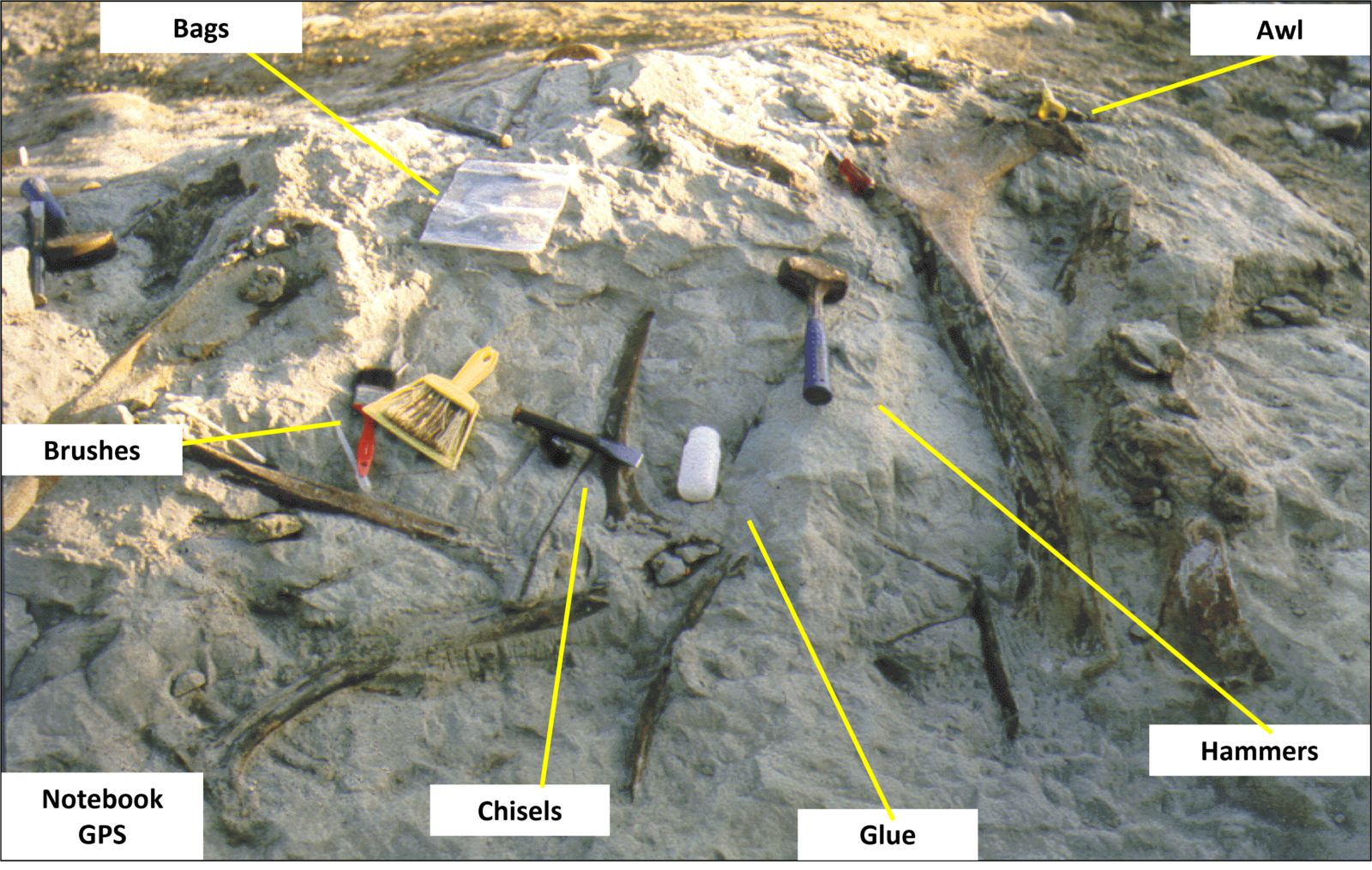

The crime-scene investigator typically carries a case that contains everything normally used to collect evidence (Figure 3).

This kit may be supplemented by additional tools, depending on the complexities of the crime scene; a standard tool kit includes crime scene tape, camera and video equipment, a sketchpad and pens, a magnifying glass and tweezers, evidence bags, fingerprint casting kits, and glue. All these items would also feature in the geologist’s field bag, along with hammers, chisels, and awls (Figure 4). Additional items used at crime scenes usually include protective clothing, a flashlight, UV light, laser, infrared (geologists generally don’t need to work in the dark but use lasers to scan rocks in 3D), a serology kit, and an entomology kit.

BACK AT THE LAB

Soil analysis can be very valuable tool in identifying where the crime took place. This is comparable to examining thin sections and cuttings, which can help to pin down grain size, sorting, composition, and provenance. The analysis of tool and drag marks (Figure 5) and impressions can narrow down the murder weapon and how the victim was moved. In geology, the sedimentary structures can show current direction, and there may be bite marks and scratches on bones. Both sciences use chemistry in various ways, and there are many types of trace evidence (e.g., hairs, fibres, materials of all kinds). Ichnological traces also provide important evidence of victim (i.e., the organism/fossil) behaviour. Firearm examination may also be very useful in solving crimes.

- Figure 5. Paleocene crocodile aquatic feet dragging traces

- Figure 6. Tyrannosaurus rex autopsy (www.livescience.com)

PROCESSING THE BODY

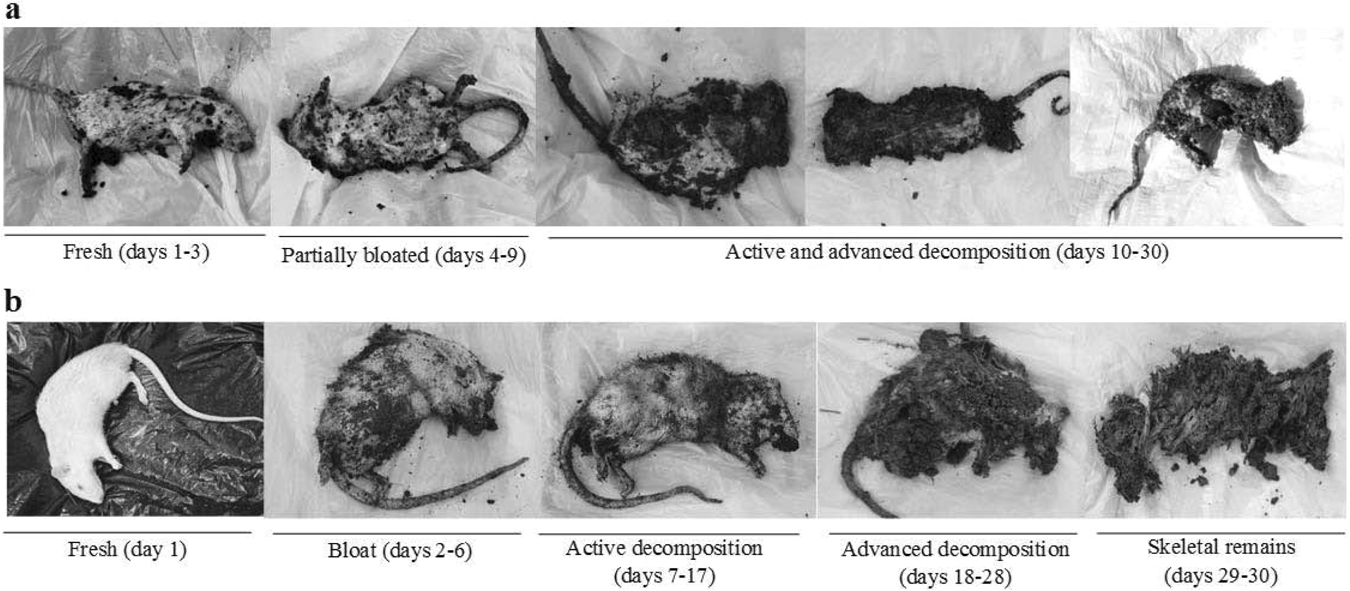

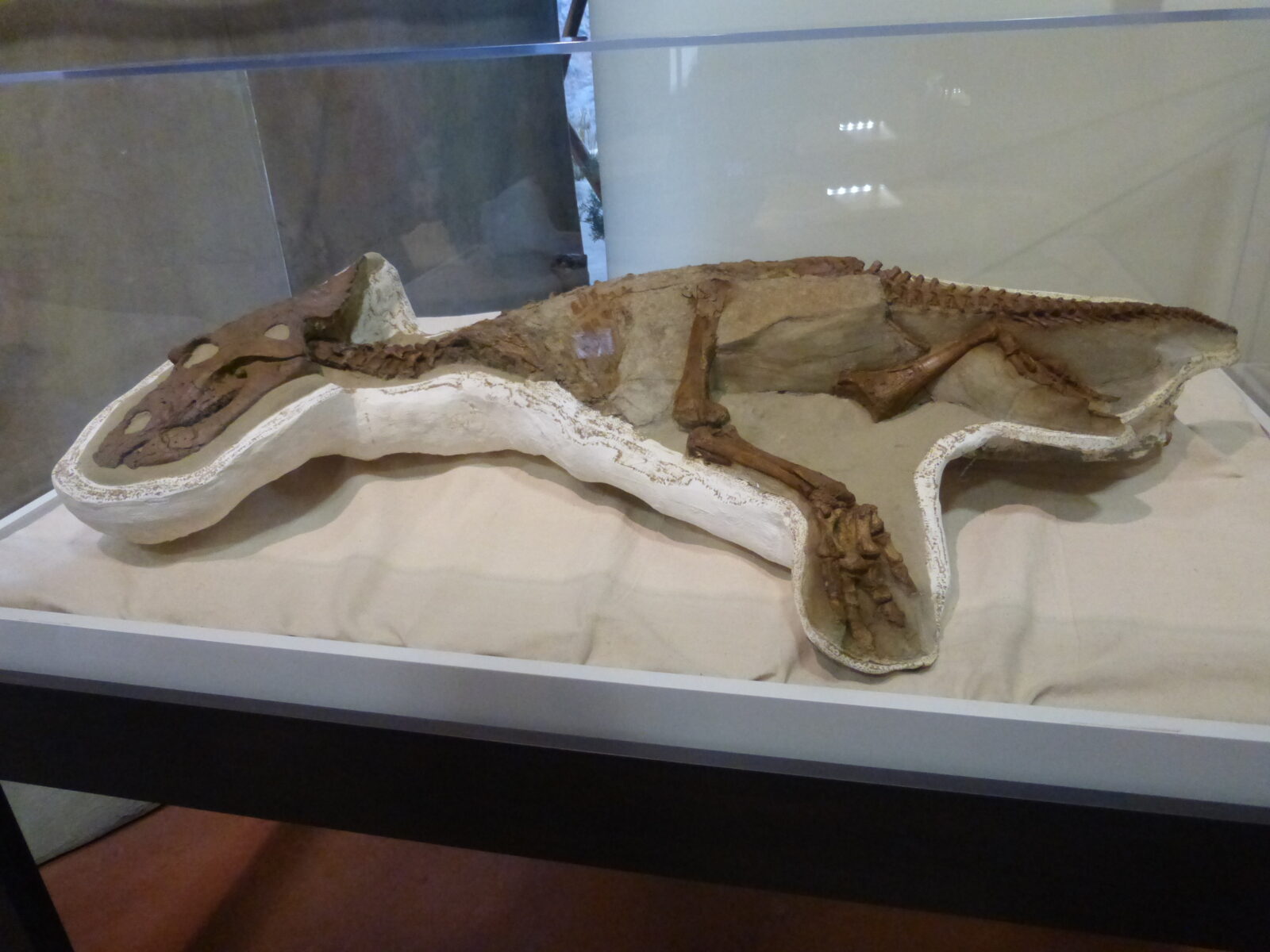

We are all familiar with autopsies. The coroner measures the body’s height and weight, takes photographs, and attempts to determine the time and cause of death (COD) (Figure 6). They look for possible trace evidence, test for toxicology, and look for artefacts, scars, tattoos, and signs of disease. The condition of the carcass (Figure 7) and insect remains may help to determine how long the carcass has been outside. Fingerprints and dental records are collected and the skeleton is

analyzed to attempt to determine age, stature, sex, and possibly race. It may even be possible to reconstruct the face of our victim.

Speaking as a palaeontologist, I can confirm that we collect an almost identical dataset, particularly when working on a fossil vertebrate. Its length is measured, and muscle scars on the bones are used to reconstruct the tissue distribution and weight. Evidence of skin is treasured or, in extraordinary cases, even internal organs may be preserved. The degree of decay of the carcass may also indicate how long it was exposed before burial. The COD may be recorded in the sediments in which the animal is preserved (especially if the death was catastrophic, such as due to fire or predation). Overall, I think palaeontologists have something to learn from modern autopsies, including facial reconstruction techniques and identifying the manner of death.

————————————————————————————————————————————-

EGU Case File DINO 7oo1

2. THE AUTOPSY

• Victim beheaded

• Skeleton of body absent

• Victim: John/Jane Dino

• Cause of Death (COD): unknown

————————————————————————————————————————————-

TIME OF DEATH (TOD)

I suspect that estimating the time of death is not nearly as straightforward as the forensic crime shows seem to make it. These estimates are based on real data often gathered during close examination of the corpse. It is not as easy when animals have been dead for millions of years but, geologically, time of death can be estimated from associated microfossils and macrofossils or by correlating sedimentary deposits or significant horizons to those in other areas. Ash beds are also useful chronological markers for dating.

————————————————————————————————————————————-

EGU Case File DINO 7oo1

3. TIME OF DEATH (TOD)

• TOD confirmed as 75.94 Ma

• Based on associated fossil oyster bed,

indicating a marine incursion

• Timeline can be correlated to other mass

mortalities

————————————————————————————————————————————-

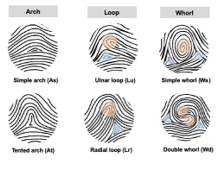

FINGERPRINTS

Fingerprints comprise friction ridges on finger pads. They were first classified (Figure 10) by Purkinje in 1823, a classic of scientific literature. The oldest prints date back 6000 years to earthenware on

an archaeological site in northern China (Holder et al. 2003). They are subdivided into patent prints (made of a substance), plastic prints (pressed into soft material), and latent prints

(invisible to the naked eye). Superglue vapour can be used to tease out prints on many surfaces. Complex digital technology is used to clean up and process fingerprints and this process could readily be applied to palaeontological remains, especially trackways and skin impressions. Many examples of the latter have come to light over the last few years, particularly in Alberta and the US, and a database might help with identifying the types of dinosaurs involved.

————————————————————————————————————————————

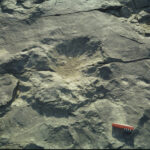

EGU Case File DINO 7oo1

4. FINGERPRINTS (SKIN IMPRESSION):

VERY YOUNG DINOSAUR

• Skin impression preserved as ironstone cast

• Small features may indicate a juvenile

• These fossils may be overlooked in the field,

especially if poorly preserved

————————————————————————————————————————————-

BLOODSTAINS

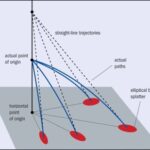

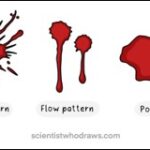

Bloodstain analysis is a key tool in interpreting crime scenes. The shape and location of the drops provide directionality (Figure 12). Blood oozes, gushes, or drips before clotting, leaving elongated ovals when falling from a narrow angle (Figure 13). The forensic analyst looks for the point of convergence (2D) and point of origin (3D). Prior impact (a gunshot or blow) will affect the velocity of the spatter. Blood may also be transferred to other objects.

- Figure 12. Blood-drop trajectories (www.Physicsworld.com)

- Figure 13. Types of blood stain (www.Scientistwhodraws.com)

Geologists already look at raindrop impressions (Figure 14), utilized as traces of ancient weather. They can provide data on wind direction and velocity. It may also be possible to identify water shed by prehistoric animals when shaking themselves after getting wet. The interpretation of other types of traces, such as squelch prints (left by vertebrates in mud, much like the reader in wellies; Figure 15) could be enhanced using forensic techniques.

- Figure 14. Modern raindrop impressions, North Calgary, Alberta

- Figure 15. Squelch print left by Bradysaurus, Gansfontein Farm, South Africa

- Figure 16. Miocene mangrove lobster trackways made by a “shrimp with a limp”, Sandakan, Eastern Borneo

While many of the same techniques are used in both forensic science and sedimentology, the former has better databases and search engines. It also use items like spray lacquer to preserve tracks in soft mud. Palaeontologists use modelling software to reconstruct how tracks were made (including animals with limps; Figure 16); this software could easily be applied to crime scenes.

———————————————————————————————————————————-

EGU Case File DINO 7oo1

5. IMPRESSIONS: SMEARED MUDCLAST BED

WITH BONES (ARROWED)

• Trace evidence at crime scene

• Mud clasts suggest fast flowing current

• Scattered bones indicate a possible death

assemblage

————————————————————————————————————————————-

ARSON

Figure 18. Fossil tree with coalified

rim that may represent burning, Late

Cretaceous, Springbank, Alberta

While not part of our crime scene, evidence of prehistoric forest fires is common. Modern investigations into arson look for the point of origin and the cause of the fire. A fire needs fuel, oxygen, and heat. Experts analyse wood and how structural materials have been affected. Match heads contain diatoms that can be discerned after a fire. Combustible compounds can be identified by gas chromatography or mass spectroscopy. Many techniques can be applied to ancient fires,

including estimating the heat generated, determining how the fires spread, and using spectroscopy on burnt wood (Figure 18).

————————————————————————————————————————————

Figure 19. Fossil wood, possibly from Metasequoia (dawn redwood), Campanian, Princess South, Alberta

EGU Case File DINO 7oo1

6. FOSSIL WOOD IN GOOD SHAPE

• No evidence of arson

• Suggests that food was plentiful

————————————————————————————————————————————-

EGU Case File DINO 7oo1

VICTIM: JUVENILE CENTROSAURUS

COD: DROWNING.

SKELETON DISSOCIATED AFTER DEATH

————————————————————————————————————————————-

SUMMARY

There is undoubtedly cross-over between forensic science and sedimentary geology and palaeontology. These sciences use data collected at the crime scene to understand what happened at the time of death or deposition. There is clearly a huge opportunity for the two branches of science to learn from one another. New forensic techniques are continuously being developed and have the potential to be applied to many sedimentary conundra. Finally, I see no reason why a sedimentology related TV series cannot attract a similar audience to NCIS and Criminal Minds: I suggest calling it “Clastic Sedimentary Investigation” or CSI for short.

REFERENCES

Holder, E.R., L.O. Robinson, and J.H. Laub. 2003. The Fingerprint Sourcebook. US Department of Justice, www.nij.gov

Iancu, L., E.N. Junkins, G. Necula-Petrareanu, and C. Purcarea. 2018. Characterizing forensically important insect and microbial community colonization patterns in buried remains. Sci. Rep., 8 (2018), p. 15513.

Lyle, D.P. 2019. Forensics for Dummies. 2nd Edition. Learning Made Easy, Wiley. 382 pp.

Purkinje, J.E. 1823. Commentary on the Physiological Examination of the Organs of Vision and the Cutaneous System. Unpublished thesis.