Introduction

Introduction

Bird footprints are some of the most recognizable traces in the fossil record. Yet birds exhibit a wide variety of behaviours which may be preserved as ancient traces. Records include feeding traces like probing, nesting structures and possibly coprolites, but the study of the traces left by modern birds extends their scope to courtship-related scrapes, swimming and diving traces, bird resting and perching traces and feather impressions, as well as other feeding strategies and more subtle scrape-like nests (Belaústegui et al 2017). Note that eggs are no longer classified as trace fossils. In this article we will review ancient bird traces and suggest other potential traces that have not previously been identified as fossils.

Evidence suggests that birds “took flight” around 145 million years ago (Lockley and Harris 2010), the same age as Archaeopteryx. Tracks similar to those made by modern shorebirds, ducks, herons and roadrunners appeared in the fossil record and became abundant over the next few million years. In contrast, the earliest body fossils of these birds date back only 70 million years, suggesting that early track makers were members of extinct lineages with similar feet and behaviours, including feeding strategies (Lockley and Harris 2010). The enantiornithines were the dominant avians in the Mesozoic (with clawed fingers on their wings and teeth), with Neornithes dominating throughout the Tertiary (Mainwaring et al 2023). The latter can be delineated based on a backward pointing hallux, wide divarification (the angle between outer digits) and no heel pad (except large terrestrial birds).

As we will see, fossil bird traces are dominated by shorebirds (Lockley and Harris 2010), with many records of bird footprints and some feeding traces. This relates to their taphonomy (the study of how organisms decay and become fossilized or preserved in the paleontological record) where coastal settings preferentially preserve bird traces due to their soft substrates, abundant fauna and food sources, and changes in water depth allowing traces to quickly be covered and potentially fossilized.

1. Miocene bird footprints from Sandakan, eastern Borneo

Bird footprints

Tracks are by far the most common bird traces. Most animals will make tens of thousands of footprints but only have a single carcass to contribute to the fossil record, should scavengers and taphonomy allow it. Fossil bird footprints date back to at least the early Cretaceous: there is some evidence for Triassic trackways, but these were probably made by bird-like therapod dinosaurs (Wikipedia), with most Cretaceous records from Asia (Lockley and Harris 2010). As mentioned, these tracks are all very similar to modern bird traces.

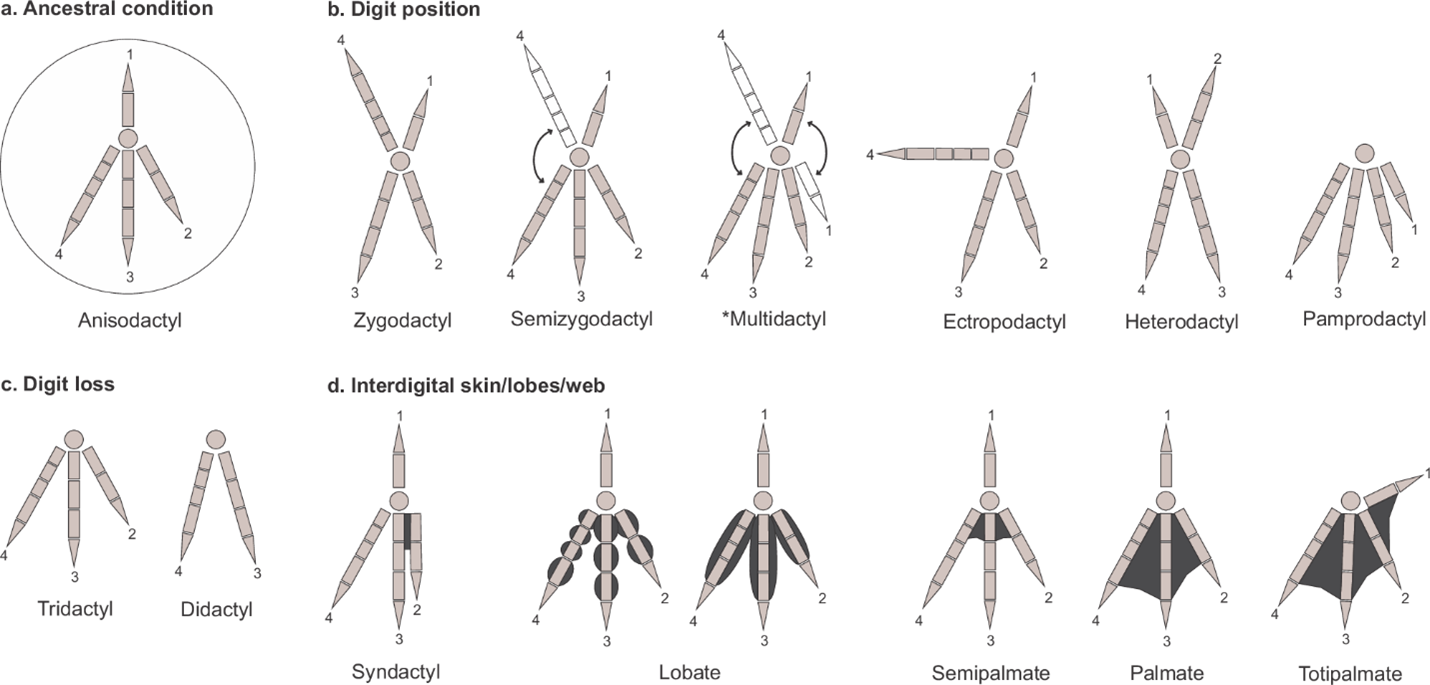

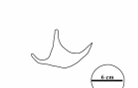

The morphology of a bird footprint is very variable depending on its lifestyle. Avian feet are traditionally classified in several categories based on the number of digits, and their positional arrangement and mobility. These categories include the following (Elbroch and Marks 2001; Carril et al 2024):

| Footprint type | Description | Examples |

| Classic bird tracks (anisodactyl) | three toes forward and one pointing back, common | herons, egrets, crows, eagles, hawks and falcons, moorhens, crows, swallows, kingfishers, thrushes, sparrows, spoonbills, etc. |

| Game bird tracks (technically anisodactyl) | hallux greatly reduced or absent, may be raised, termed incumbent | Game birds, shorebirds (partially webbed feet are termed semipalmated; rails, coots, plovers, oystercatchers, stilts, sandpipers, phalaropes, turkeys, grouse, etc. |

| Webbed or palmate tracks, anisodactyl | Toe 1 (hallux) absent or tiny, fully webbed | Loons, swans, ducks, avocets, gulls and terns, flamingos |

| Totipalmate | Also webbed but webbing extends to toe 1, toe 4 is longest | Boobies, gannets, pelicans, cormorants |

| Zygodactyl | Two toes forward and two back, second most common | Woodpeckers, cuckoos (roadrunners), parrots, owls, ospreys |

Table 1. Basic classification of bird feet

For our purposes, we are really concerned with four toed (anisoldactyl) versus three toed (tridactyl), and whether the feet are fully or partially webbed, or not webbed. Shorebirds (and other birds) mentioned in this article are in bold.

2. Bird foot types (from Carril et al 2024)

With the bias towards shorebirds tracks in the ancient (Greben and Lockley 1993), the most common fossil bird footprints are anisodactyl and tridactyl, with varying degrees of webbing. The presence or absence of hallux (the rear facing claw in anisodactyl tracks) is also important in their classification, although differing substrates may mean that the bird may have a hallux but that it does not register as an impression.

The KSU website lists 42 species of fossil bird footprints. In terms of depositional setting, 34 were deposited on the water margin or lake and 6 were continental deposits. Twenty-five are shoreline birds, 5 are flamingo, pelican or anseriform (duck), 4 are fully terrestrial and the rest were not identified.

- 3 Modern duck footprint from Calgary, Alberta

- 4 Modern trample zone AKA bird disco, where many birds have walked in the same area, Lethbridge, Alberta

Classification of fossil bird footprints

Fossil bird footprints are classified based on their morphology, using a similar Linnean naming system to body fossils (ichnotaxa). These can be grouped into ichno-groups, which tend to occur in particular ichnofacies (sediment types) or ichnocoenoses (environments) (Lockley et al 2021). Types of footprints are NOT tied to a particular bird, which is very important as different animals can make identical traces due to similar behaviours (Lockley and Harris 2010). Common track types have been recorded over intervals from the Cretaceous to Recent, including examples such as:

Table 2. Common bird footprints (after Kim et al 2012; Fiorillo et al 2011; Carmens and Worthy 2019; Lockley et al 2021)

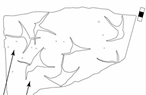

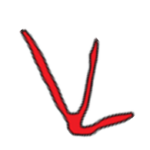

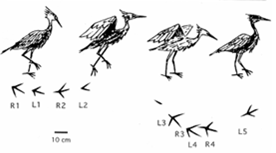

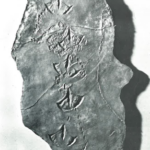

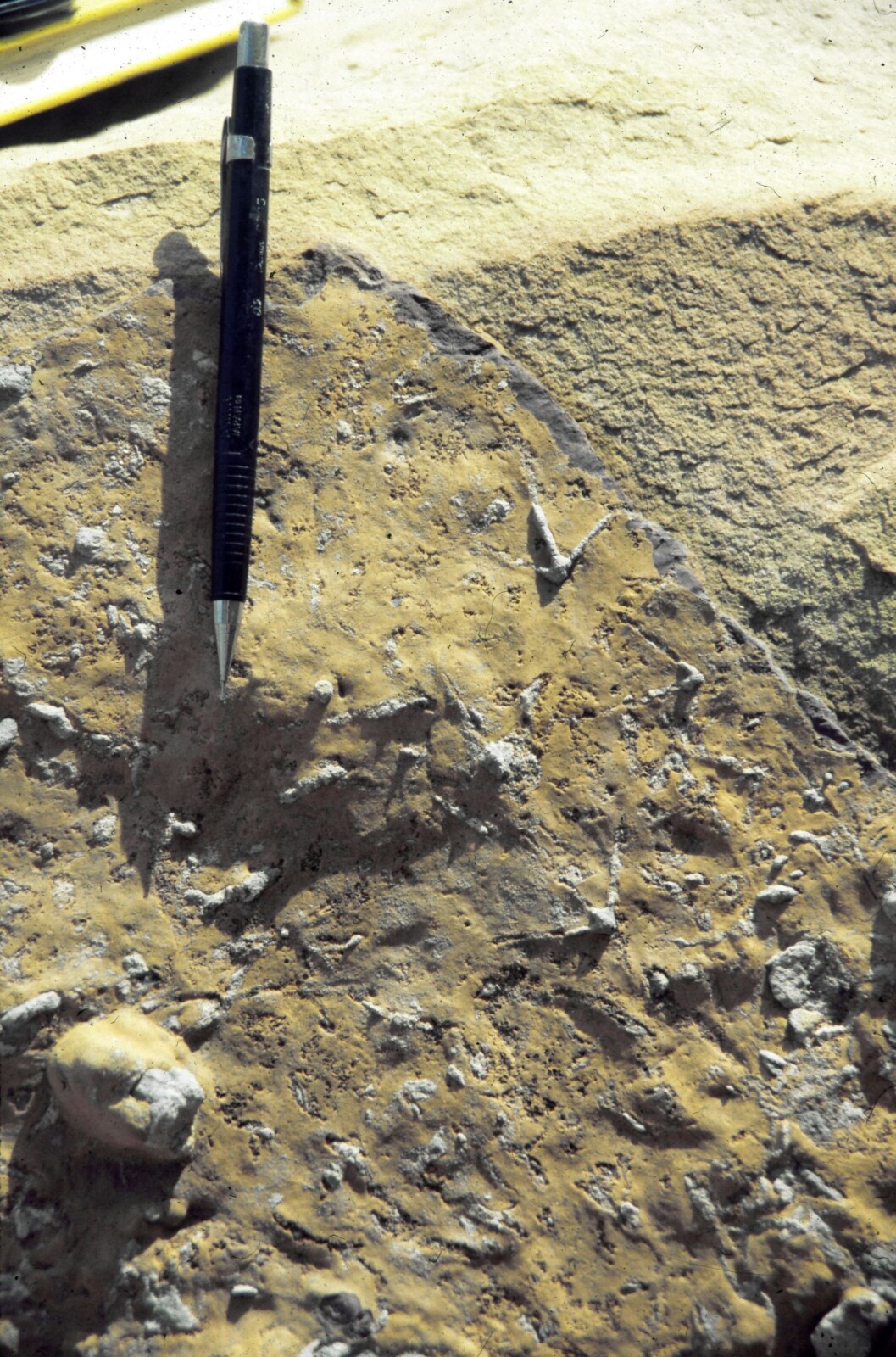

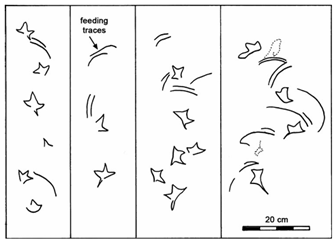

A comparison of fossil and recent bird tracks is informative. Fossil bird footprints were discovered in Miocene mangrove deposits in Sandakan, Sabah, eastern Borneo (Noad 2005; 2013; 2017). Their mangrove origin was confirmed by the presence of fossil mangrove lobsters (Thalassina anomala). The footprints were tridactyl with straight digits and a wide divarification angle and lacked a hallux. A study of modern bird traces found many similar tracks, but most retained a hallux (stilts, moorhens, rails, oyster catchers, sandpipers, ibis). Plover and (closely related) killdeer footprints appeared most similar, both being upland shore birds, around 23 to 27 cm in length. This suggests that a Miocene bird, walking like a plover, with similar feet, left these tracks in the mud beneath a mangrove channel.

6. Interpreted bird footprints (in red) from the Miocene Sandakan Formation, Sandakan, eastern Borneo. The tracks are preserved as cemented mudstone casts on the base of a mangrove channel sandstone. Note the association with prod marks (highlighted in white).

- Killdeer footprint

- Killdeer footprint sketch

- Killdeer

- Sandakan Fm footprint

- Sandakan footprint sketch

The bedding plane also exposed a series of small, circular traces which are interpreted as prod marks. Other examples of prod marks are discussed in the Feeding Traces section, as well as another newly reported trace from the Sandakan Formation.

8 Modern plover tracks and probe mark, Calgary, Alberta

Obviously more recent deposits, such as the Pliocene of the Lake Eyre Basin, Australia, may exhibit footprints that can fairly confidently be tied to modern birds, such as flamingos, a variety of waders and pelicans or swans. The ichnotaxa include Anatipeda, Phoenicopterichnum and Koreanaornis (Carmens and Worthy 2019).

Famous bird footprint localities

Cretaceous examples

The Cretaceous, non marine, Hamman Formation of southeastern Korea has yielded thousands of bird tracks as well as plants, freshwater molluscs and dinosaur footprints, from several sites (Paik et al 2012). The Hamman Formation is composed of reddish shales and fluvial sandstone. At the Gajinri site, interpreted as a lakeshore deposit, the density of bird footprints may be up to 600/m2 (Kim et al 2012). More than 1000 bird tracks are exposed on a single bedding plane at the Gyeongsangnam-do Institute of Science Education (GISE) in Jinju, with impressive morphological and behavioral diversity. These range from a variety of feeding strategies (see below) to landing and running traces (Falk et al 2014).

The current named ichnogenera from the Haman Formation include: Koreanaornis (a small incumbent anisodactyl track possibly lacking a hallux), Ignotornis sps. (semipalmated tracks) and Goseongornipes (similar to Koreanaornis and smaller than Ignotornis and Hwangsangornipes). Koreanaornis and Goseongornipes tracks would be made by shorebird-like birds similar to sandpipers and plovers (Falk et al 2014). There are also Jindongornipes, Uhangrichnus (webbed) and Hwangsanipes (Lockley et al 2012). The palaeoclimate was thought to be warm and dry (Paik et al 2012) with dessication cracks and evaporite deposition.

The Upper Cretaceous Cantwell Formation in Denali National Park and Preserve (DENA), Alaska, contains an unparalleled fossil avian biodiversity (Fiorillo et al 2011). Bird tracks are preserved in multiple locations along a 40-km transect in DENA in fluvial and lacustrine deposits. The approximate body sizes of the birds based on tracks show a range from sparrow- to heron-sized birds, with Aquatilavipes, Ignotornis, Magnoavipes, Gruipeda and Uhangrichnus sp. Other localities include southern Australia (early Cretaceous) with tridactyl, partially webbed Avipeda (Martin et al 2023).

Paleogene examples

The Eocene Green River Formation in Wyoming and Utah is also famous for its fossil bird footprints and the Uinta Basin has 10 trackway localities including the webbed Presbyorniformipes. More localities outcrop in the adjacent Green River Basin and are often laterally extensive along strike (Moussa 1968). Other morphologies include Gruipeda and Avipeda, made by shorebirds similar to plovers and sandpipers. In general, the footprints are abundant but of low diversity, with small wading birds the most common but larger birds also present (Curry 1957). The footprints are preserved in very fine-grained, dolomitic limestone (Curry 1957; Moussa 1968), similar to the Solnhofen Limestone. Ripples are rare (Moussa 1968) and do not host footprints, but there are mud cracks and raindrop impressions on what was probably a muddy shoreline, subject to periodic emergence (Curry 1957).

- 9a Fossil, semipalmate bird footprints of the Green River Formation (Virtual Petrified Wood Museum website)

- 9b Typical sample of the Green River limestone with fossil tridactyl bird footprints

Late Eocene tracks are also found in Presidio County, Texas, including Gruipeda, Avipeda and several other species (Hunt and Lucas 2007). Diatryma tracks (a very large terrestrial bird) were found in the Eocene of Washington (Hunt and Lucas 2007). The same area exposed the Eocene Chuckanut Formation with heron-like tracks of Ardeipeda; webbed bird tracks of Charadriipeda sp. (lacking a hallux) and small shorebird tracks of Avipeda sp. The heron tracks show gaps, with the hopping gait representing a possible hunting strategy (Mustoe 2002).

10 Sketch of hopping heron (based on fossil trackway) from the Eocene Chuckanut Formation, Washington State, USA (taken from Mustoe 2002)

The Upper Eocene of the southern Pyrenees, Spain, is made up of mixed intertidal flat. sandy beach facies, different types of heterolithic, backbarrier deposits and conglomeratic, fluviatile facies. The tidal flat deposits contain abundant footprints of aquatic birds including Charadriiformes: Charadriipeda (plover-like) and a new ichnotaxon, Leptoptilostipus. The bird tracks and flat-topped wave ripples indicate falling water levels, while the raindrop marks, desiccation cracks, pseudomorphs after halite and adhesion ripples are clear evidence of subaerial conditions in an overall deltaic setting (Payros et al 2000).

Further tracks, made by small wading birds, were found in Oligocene lagoonal, calcareous shales in Zaragoza (de Raaf et al 1965). There are also much larger web-footed (heron-like) bird tracks in these deposits. Sumatran deposits of similar age contain two types of Aquatilavipes, preserved in very fine-grained sandstone (Zonneveld et al 2011) in an intertidal flat setting. These tracks are most similar to those produced by small shorebirds such as avocets, sandpipers, stilts, rails and plovers. The second track type are more like rail tracks (Zonneveld et al 2011).

Eocene trace fossils from South Kalimantan include nine avian footprint ichnogenera (Aquatilavipes, Archaeornithipus, Ardeipeda, Aviadactyla, cf. Avipeda, cf. Fuscinapeda, cf. Ludicharadripodiscus, and two unnamed forms). They were found in a coal mine and were associated with avian feeding and foraging traces (Zonneveld et al 2024a). The depositional setting is interpreted by the authors as channel-margin intertidal flats in a tide-influenced estuarine setting.

Neogene examples

Fossil bird footprints are much more common in the Neogene. Miocene lacustrine deposits in Death Valley preserve a variety of tracks, including large avians. There are many other US Miocene bird footprint localities (Hunt and Lucas 2007) including Lake Mead, New Mexico and the Texas Panhandle. An Iranian locality in the west Zanjan province has yielded abundant tetradactyl Iranipeda isp., Ornithotarnocia isp., and webbed Culcitapeda tridens footprints, laid down in a playa setting (Khoshyar et al 2016).

In Argentina, the Miocene Toro Negro Formation in La Rioja province contains Fuscinapeda sp. preserved in flood deposits in an anastomosing fluvial system. More of these prints have been found in Andean intermontane basins (Krapovickas et al 2009). The Toro Negro palaeo-community consists of three different birds (a perching bird, a shorebird, and a large cursorial bird), with some footprints preserved in channel top deposits.

Large, tridactyl bird footprints of Miocene age were found in sandstone blocks in the Ebro Basin of Spain (Diez-Martinez et al 2016). They include Uvaichnites, with slender digits, no hallux and no webbing, made by a bird similar to a modern crane. Associated tracks from other localities include Charadriiformes (waders and gulls), Anseriformes (ducks and geese), and Ciconiiformes (storks and herons) (Doyle et al 2000).

Another famous Miocene site in Spain is in Sorbas, Almeria Province. Three distinctive avian ichnotaxa can be identified: Antarctichnus, Iranipeda and Roepichnus sp. These traces are associated with shorebirds, including plovers, storks, ducks and/or gulls, respectively. They are preserved in lagoonal marl deposits behind a coastal barrier with an overall tidal signature, with abundant herringbone cross-stratification (Doyle et al 2000). There are also fossil insects and mammalian tracks. The excellent fossil preservation suggests that the water saturation state was closest to the moist-damp/stiff-moderate category, and therefore the optimum for preservation of tracks (Doyle et al 2000).

- 11 Fossil bird tracks from Sorbas, SE Spain

- 12 Herringbone cross-stratified sandstone from Sorbas, SE Spain

Well preserved Pleistocene footprints were discovered on the southern coast of Buenos Aires province in Argentina in siltstone, sandstone and claystone outcropping along a beach for at least 10 km. These are thought to be fluvial flood deposits and host four bird ichnotaxa including Phoenicopterichnum, Charadriipeda, Gruipeda and Aramayoichnus (a large, rhea-like bird) sp. (Aramayoa et al 2015). These contrast with Pleistocene coastal aeolianites of Portugal, which contain traces attributed to coots (Gruipeda), jackdaws and owls, the latter a possible feeding trace (de Carvalho et al 2023).

Holocene fossils have been found around Formby Point, UK, including human footprints and those of wading birds, between 7500 and 4500 years old. Oystercatcher prints are the most common and there are also crane tracks and mammal tracks outcropping along the formerly reed fringed coastline (Roberts 2009). It is likely that offshore barrier islands deflected the force of the waves, allowing muds to be deposited at the coast (Roberts 2009).

13 Large deer tracks from Formby, showing the style of preservation in the Pleistocene muds

Modern settings such as Cooking Lake, 25 km southeast of Edmonton, provide useful neoichnological data (Kimitsuki et al 2024) including tracks, trackways, and trampling marks found along the lake margins. Most tracks were incumbent anisodactyl (tridactyl; incipient Koreanaornis). Webbing was only noted in one palmate trackway. Trample grounds are found just above the high-water mark.

Feeding traces

Birds use a wide variety of feeding strategies. Shorebirds use a subset of these techniques, many of which have been identified in the fossil record. These include the following:

Probe and peck marks

Several dozen near-circular to sub-oval depressions are associated with the Ignotornis and Aquatilavipes tracks at DENA and are interpreted as shallow punctures produced by the narrow bill of a bird (Fiorillo et al 2011; Falk et al 2014). The DENA features compare well with probe marks produced by modern members of the Charadriiformes, which include plovers, woodcocks and other birds (Elbroch and Marks 2001). Some are conical, some twinned.

Similar probe and peck marks were seen in Cretaceous deposits of Korea (Falk et al 2010), associated with web footed Koreanaornis bird tracks. Clustered probing has also been observed (Elbroch and Marks 2001; Falk et al 2014), although isolated probes are more common. Among the arcuate traces of Ignotornis gajinensis is a small elliptical indentation that may represent a jabbing motion or peck by the spoonbill-like bird responsible for the trace (Falk et al 2014).

Zonneveld et al (2011) described numerous small scratch marks, divots and pits occurring on the bedding planes co-occupied by avian and invertebrate trackways in the Ombilin Basin, Sumatra. They consider these markings similar to probe and peck marks that occur in the Cretaceous Haman Formation of Korea (Falk et al., 2010) and Cantwell Formation of Alaska (Fiorillo et al., 2011), and to peck marks and probe marks emplaced during foraging activities in modern lakeside and intertidal flat settings.

Zonneveld et al (2011) described numerous small scratch marks, divots and pits occurring on the bedding planes co-occupied by avian and invertebrate trackways in the Ombilin Basin, Sumatra. They consider these markings similar to probe and peck marks that occur in the Cretaceous Haman Formation of Korea (Falk et al., 2010) and Cantwell Formation of Alaska (Fiorillo et al., 2011), and to peck marks and probe marks emplaced during foraging activities in modern lakeside and intertidal flat settings.

14 Plover prod marks, modern, Glenmore Reservoir, Calgary, Alberta. Note the twinned bills. US cent for scale.

A coal mine site in Kalimantan (Zonneveld et al 2024a) exposed both tracks and associated traces including small, shallow, circular to ovoid divots and pits (Type I traces), V-shaped gouges (Type II traces), and other traces (see below). Type I traces are consistent with either probe marks or peck marks reported from modern shorebirds (Elbroch and Marks 2001; Falk et al 2010; Zonneveld et al 2011) and were not aligned, suggesting random probing. Type II traces are consistent with pecking and scratching. Peck marks are emplaced when the food resources are at, or near, the sediment surface (Zonneveld et al 2024a).

Modern plovers peck or probe an average of 5 to 7 times per minute while foraging for tiny crustaceans. An example of probe marks made by a plover are shown in the photo below. Note the linear sets of probes and slight elongation due to the beak being slightly open.

Observations at Cooking Lake identified modern feeding traces including probe marks in isolation, clustered or aligned. Some traces appear as paired probes, made by birds with open beaks. Most shorebirds were observed probing sporadically along the lake margins (Kimitsuki et al 2024). Avian tracks are distributed along lake shores, with higher concentrations found closer to the water’s edge, though not within the water itself, probably representing changes in the firmness of the substrate.

Foot stirring

There is evidence that the Ignotornis trackmaker sometimes used a shuffling gait that could be inferred as a foot-stirring strategy designed to raise food from the substrate where it foraged. The foot shuffling behavior has only been noted in trace fossils from the Cretaceous of Colorado (Lockley and Harris 2010; Kim et al 2012). Modern herons are known to use this hunting strategy (Lockley and Harris 2010).

Dabbling

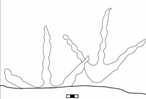

The webbed trace Presbyornithiformipes, recorded from the Eocene of North America, is associated with dabbling marks (Yang et al 1965; Lockley et al 2021). Some Cretaceous specimens of Koreanaornis trackways from Korea have associated dabble marks (Kim et al 2012).

- 15 Probable Presbyornithiformipes tracks with associated, interrupted dabble marks (taken from Erickson 1967)

- 15 Probable Presbyornithiformipes tracks with associated, interrupted dabble marks (taken from Erickson 1967)

Scything

The semipalmated, tetradactyl trace Ignotornis gajinensis, seen in Korean Cretaceous deposits, is associated with arcuate to semi circular, double-grooved, or paired impressions resulting from black-faced spoonbill-like feeding behavior (Swennen and Yu, 2005; Lockley and Harris, 2010; Kim et al 2012; Lockley et al 2012; Falk et al 2014). The birds sweep their beaks back and forth creating zig-zag, arcuate paired traces, slightly smaller than those of the modern spoonbill (Falk et al 2014). There is ichnological evidence that the birds may stop the scything behaviour in deeper water, much like modern spoonbills, and of other subtle behaviours (Falk et al 2014). Black swinged stilts also use a scythe-like feeding method, as well as peck and probe techniques. Flamingos leave very distinctive feeding traces with the birds using a similar feeding technique.

The semipalmated, tetradactyl trace Ignotornis gajinensis, seen in Korean Cretaceous deposits, is associated with arcuate to semi circular, double-grooved, or paired impressions resulting from black-faced spoonbill-like feeding behavior (Swennen and Yu, 2005; Lockley and Harris, 2010; Kim et al 2012; Lockley et al 2012; Falk et al 2014). The birds sweep their beaks back and forth creating zig-zag, arcuate paired traces, slightly smaller than those of the modern spoonbill (Falk et al 2014). There is ichnological evidence that the birds may stop the scything behaviour in deeper water, much like modern spoonbills, and of other subtle behaviours (Falk et al 2014). Black swinged stilts also use a scythe-like feeding method, as well as peck and probe techniques. Flamingos leave very distinctive feeding traces with the birds using a similar feeding technique.

16. Sketch of Igotornis tracks with associated parallel grooves attributed to sweeping bill movements (from Lockley et al 2012)

- 17 Flamingos and their nests, which could potentially be fossilized (www.sonomabirding.com)

- 18 Flamingo feeding trace – attribution “photo from Twitter”

The Kalimantan coal mine mentioned above (Zonneveld et al 2024a) also exposed straight to gently arcuate paired and singular grooves (Type III traces) and dimpled surfaces (Type IV traces). Type III traces are similar to sweep (or scything) marks created by water birds foraging in shallow water (Swennen and Yu 2005; Lockley et al 2012). Spoonbill sweeping results in paired, arcuate grooves that show a back-and-forth pattern (like avocet feeding traces), often overlain by footprints (Zonneveld et al 2024a). The dimpled surface can result from microbial binding or intense avian activity, the latter interpretation favoured due to the abundant bird footprints (Zonneveld et al 2024a).

Swishing

Certain modern birds move their heads back and forth through the sediment to sift for food. The movements are less extreme than those of spoonbills or avocets. A new discovery from Miocene deposits of the Sandakan Formation shows the first report of a fossil swish trace preserved in a sandstone bed. The fossil occurred 4 m below a bed exposing fossil bird footprints (see Footprints section), in a mangrove channel composed of sandstone.

- 19 Modern swish feeding traces, possibly made by a plover at Glenmore Reservoir, Calgary, Alberta. Field of view 15 cm.

- 20 Modern swish trace made by a blacksmith plover, St. Lucia estuary, South Africa

- 21 Outcrop of the Sandakan Formation, eastern Borneo, exposing Miocene mangrove deposits with associated fossil bird feeding traces.

- 22 First report of fossil “swish” bird feeding trace from the Miocene Sandakan Formation, eastern Borneo. Propelling pencil for scale.

- New type of fossil bird feeding trace from the Miocene of eastern Borneo

Other types of feeding trace (not yet seen as fossils)

Other feeding strategies that may be utilized by birds include killing sites, where kites drop snails onto a rocky surface to break them open. Golden eagles will catch tortoises and then drop them onto rocks to break the shells, providing access to the flesh within. Allegedly Aeschylus, an ancient Greek tragedian, died in 456 or 455 BC when an eagle dropped a tortoise on his bald head, mistaking it for a rock.

Up to 23 species of bird, including gulls, crows, eagles and vultures, will take advantage of rocks to crack nuts, molluscs and hard-shelled food. Western gulls drop Washington clams, using different heights depending on the size and thickness of the shells. Anecdotal evidence suggests that bearded vultures will do the same to mountain goats, knocking them off ledges (www.cracked.com: www.audubon.org). A fossil locality littered with smashed tortoise shell or clams would likely represent a potential fossil feeding trace site.

Certain woodpeckers stash acorns in cracks in the trunks of trees. Other birds (and mammals) store food the winter. It should be possible to identify such caches in the fossil record. Ostriches make holes in the ground (and do literally push their head into the ground) when looking for grubs. Birds may also leave wing marks in fine grained sediment when swooping down to catch crabs or small mammals, or simple scratch marks when foraging for seed. Once again, the mantra is to keep an open mind when examining sedimentary rocks deposited in a terrestrial setting. There may be feeding traces, burrows and more awaiting the ichnologist.

- 23 Example of an invertebrate killing field, with herring gulls dropping gastropods in order to break them open, Norfolk, UK

- 24 Example of broken tortoise shells dropped by kites (location unknown)

Nesting sites

The nests of euornithine birds—the precursors to modern birds—were probably partially open and the neornithine birds—or modern birds—were probably the first to build fully exposed nests. The apparent trend through time has been towards more complex nesting structures and fewer offspring, possibly related to greater cognitive functions (Mainwaring et al 2023).

Early nests were probably scrapes, or eggs were buried. Pedogenesis would destroy many of these structures. Exposed nests allow greater parental care, including for later dinosaurs such as maiasaurs, ornithoraptors and Troodons (Horner 1984). Their nests were bowl shaped with a distinct rim. Cretaceous enantiornithines nested among sand dunes in Argentina, with their eggs half buried in sediment (Fernandez et al 2013), in contrast to most neornithines. The open nests of the neornithines may have helped them to survive the mass extinction event (Mainwaring et al 2023).

Fang et al (2018) surveyed all 242 bird families and found that 60% nest in trees, 20% nest in non-tree vegetation and the remaining 20% nest on the ground, in riverbanks or on cliffs. Cup nests are by far the most common. The development of constructed nests allowed new niches to be colonized (Mainwaring et al 2023).

- 25 Modern swallow nest constructed of mud, Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta

- 26 Pleistocene nest preserved in tufa, Germany (seen on auction site), compares to a find from Lower Fraconia, Germany. Diameter 13 cm.

In terms of fossils, very few nests have been identified, beyond the examples mentioned above and a few Pleistocene nests preserved in tufa. Another find was a hole drilled into a fossil palm stump, presumably by a woodpecker, but further details are lacking. Nests constructed from mud would seem to have a better chance of preservation in the fossil record. Such nests include swallows, who use globules of mud to construct a nest and flamingos, who build a pedestal out of mud on which to lay their egg.

It is suggested that palaeontologists look for scrapes on bedding planes, especially in overbank mudstone beds. The presence of eggshell may allow Cretaceous examples to be delineated from dinosaurs. In the Tertiary there may also be fossil scrapes, horizontal burrows into soft sediment, holes drilled into fossil wood (see above), or even masses of fossilized plant material which may in actuality be nests, although some authors do not consider these are traces (Buatois & Mángano 2011). Once again, the association with eggshell or droppings would help to confirm their avian origin. There are probably many more fossil nests than realized, just waiting to be identified.

Coprolites and Regurgitalites

Bird droppings may be petrified and preserved but may be difficult to recognize in the field. The semi liquid guano issued by many birds may be difficult to fossilize but thicker beds of ancient guano have been recorded. Coprolites are locally common in the Eocene Green River Formation of Utah, Wyoming and Colorado, particularly in environments that preserve complete fish. Some authors argue that birds are likely predators to produce coprolites with bones. In 25 Eocene assemblages, up to 69% of fish remains consist of presumed fossil pellets (Hunt and Lucas 2007).

Regurgitalites, or owl pellets, have been recognized both directly and indirectly in the fossil record. A New Mexican specimen contains cranial and post cranial material from two rodents. Some cave microvertebrate assemblages are thought to be degraded owl pellets (Hunt and Lucas 2007).

Other potential bird trace fossils

We have discussed a wide variety of bird traces. Some additional suggestions (Belaústegui et al 2017) to look out for include:

Bird resting traces.

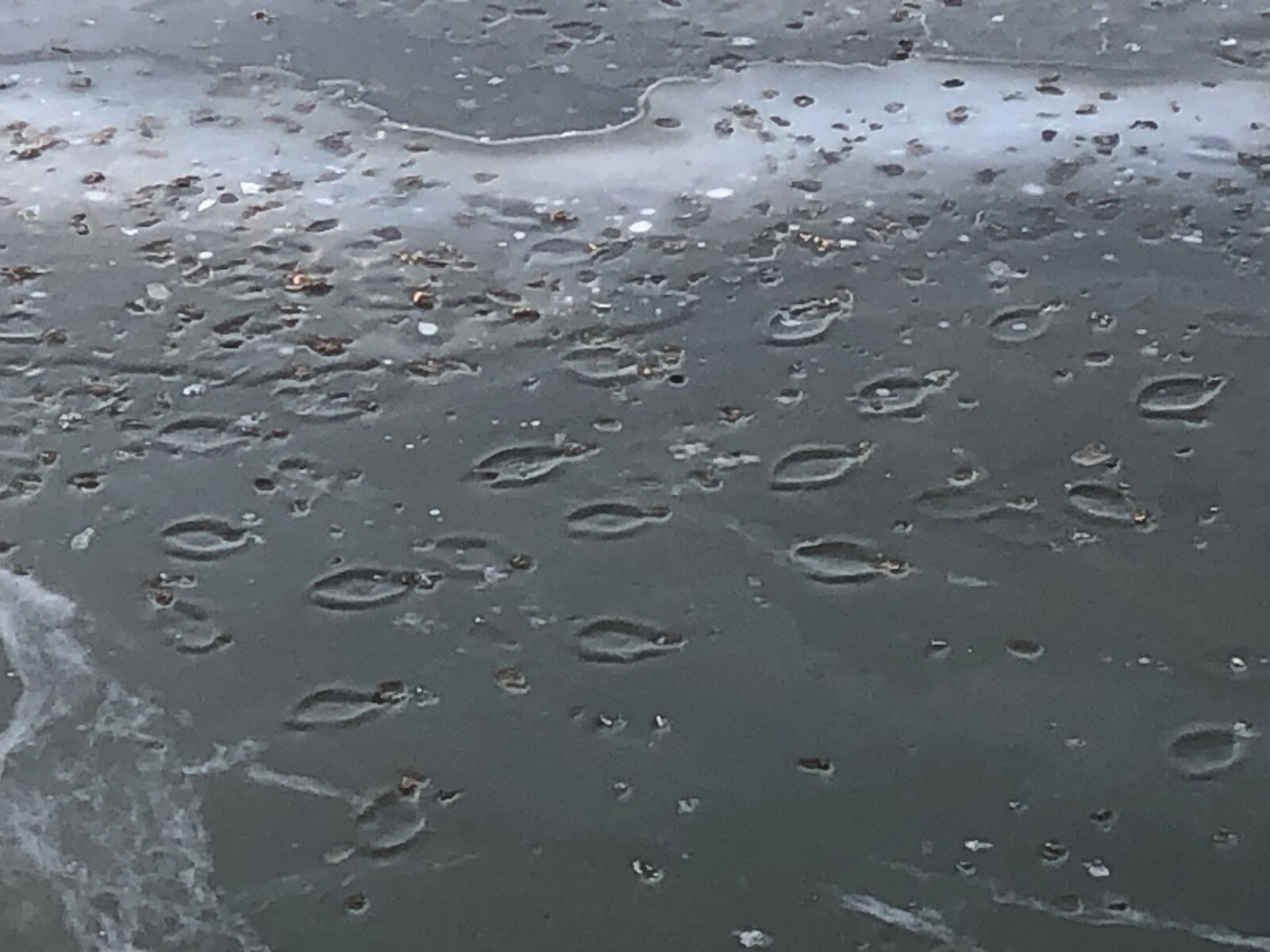

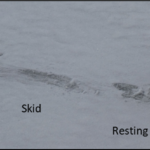

A dinosaur resting trace has been identified in the Whitmore Point Member of the Moenave Formation in southwestern Utah (Milner et al 2009), associated with a trackway and tail drags. The resting trace includes symmetrical pes impressions and well-defined impressions made by both hands, the tail, and the ischial callosity. Another example was presented by Milan (Milan et al 2008). Modern avian examples have been observed preserved in ice and snow around Calgary, Alberta. The best example is of goose resting traces (GRT) which have an oval shape with an irregularity at the rear end where the goose rested its feet on the ice. Duck resting traces are also common (but frequently soiled with excreta).

One paper (Falk et al 2014) mentioned finding an oval-shaped, slightly depressed area, bounded on one side by a crescent-shaped indentation and on the other by what appears to be a small linear trough. The authors were unable to interpret this feature but, from the description, and utilizing a neoichnological analogue, this could be interpreted as a bird resting trace.

27 Oval goose resting traces seen in ice beneath the Zoo Bridge, Calgary, Alberta. Note the small protrusions breaking the ovals to right, made by the geese’ feet. Traces are approximately 40 cm long.

Landing and Courting Traces

Another type of modern bird trace preserved in snow is landing traces, both duck and goose. There is often an initial skid mark, followed by a landing and resting trace. Wing marks are preserved to the sides of the skid as the bird tries to slow itself down. Wing marks may also be preserved in isolation during takeoff. Possible landing traces were recorded in the tracks of Ignotornis gajinensis, with the trackway having an abrupt beginning interpreted as a landing (Falk et al 2014). Elbroch and Marks (2011) describe the distinctive takeoff pattern of certain modern birds and it seems likely that these could be recognized on larger bedding planes exposing bird footprints.

- 28 Goose landing trace in snow, Calgary, Alberta, with track maker still present.

- 29 Another (duck?) landing trace with wing marks alongside. Length of trace around 2.5 m.

Dinosaur courting traces have been recognized at several locations in Colorado. Large, paired scoop shaped depressions are interpreted as leks (Lockley et al 2015). These structures may be a metre long and 15 cm deep but there are likely to be smaller ones preserved as fossils, made by predecessors of modern grouse. Imagine a bird scraping the ground with its claw to try and impress a female.

Conclusions

A wide variety of bird traces are preserved in the fossil record. The tracks are mostly from shorebirds, which is mainly due to the taphonomy of the coastal deposits. The same types of tracks keep appearing from the Cretaceous to Recent times, suggesting recurring behaviours and feet morphologies rather than the same bird species throughout. Associated with the footprints are a variety of feeding traces, including a new type of trace from the Miocene of eastern Sabah, allowing us an insight into bird behaviours.

30 Photo is interpreted to show a gull battling its reflection in a bottle, from Texel, NL

The use of neoichnology allows us to examine modern traces in detail, and to understand how they formed. It is strongly suggested that the neoichnological record be used to create templates that can be applied to ancient outcrops exposing bird footprints, to help to identify other significant bird trace fossils. These would include other types of feeding traces, landing and takeoff traces, and resting traces.

30 Photo is interpreted to show traces of a gull battlin g its reflection in a bottle, from Texel, NL

g its reflection in a bottle, from Texel, NL

Finally, I was struck by the description of a mating behaviour (Elbroch and Marks 2011) where a male plover high steps forward, taking short, stiff steps and then slams both feet down before flying straight up in the air. This behaviour can be captured perfectly in the bird’s footprints. How many other behaviours like this could we interpret, were we to really examine fossil trackways in detail? As most birds would readily tell you – the sky is the limit!

References

Abbassi, N. and Lockley, M.G. 2004. Eocene Bird and Mammal Tracks from the Karaj Formation, Tarom Mountains, Northwestern Iran, Ichnos, 11:3-4, 349-356, DOI: 10.1080/10420940490428689.

Aramayoa, S.A., de Biancoa, T.M., Bastianellia, N.V. and Melchor, R.N. 2015. Pehuen Co: Updated taxonomic review of a late Pleistocene ichnological site in Argentina. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 439 (2015) 144–165.

Baer, J. 1990. Geologic road log Spanish Fork, Utah to Price, Utah. Utah geological and Mineral Survey, open file report 181.

Belaústegui, Z., Muñiz, F., and de Carvalho, C.N. 2017. Bird Ichnology, bioturbation, bioerosion and biodeposition. Evolucao – Revista de Geistória e Pré-História. 2 (1)

BLM dinosaur footprint field trip

Buatois, L. & Mángano, M.G., 2011. Ichnology. Organism-substrate interactions in space and time, Cambridge University Press, New York, 358 pp.

https://lisabuckley.com/tag/bird-tracks accessed January 2025.

Camens, A.B. and Worthy, T.H. 2019. Pliocene avian footprints from the Lake Eyre Basin, South Australia, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 39:4, e1676764, DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2019.167676.

Carril, J., De Mendoza, R.S., Degrange, F.J., Barbeito, C.G. and Tambussi, C.P. 2024. Evolution of avian foot morphology through anatomical network analysis. Nature Communications volume 15, Article number: 9888 (2024).

de Carvalho, C.N., Belo, J., Figueiredo, S., Cunha, P.P., Muniz, F., Belaústegui, Z., Cachao, M., Rodriguez-Vidal, J., Caceres, L.M., Baucon, A., Murray, A.S., Buylaert, J-P., Zhang, Y., Ferreira, C., Toscano, A., Gomez, P., Ramírez, S., Finlayson, G., Finlayson, S. and Finlayson, C.. 2023. Coastal raptors and raiders: New bird tracks in the Pleistocene of SW Iberian Peninsula. Quaternary Science Reviews 313 (2023) 108185.

Curry, H.D. 1957. Fossil tracks of Eocene vertebrates, southwestern Uinta basin, Utah. Eighth Annual Field Conference.

Díaz-Martínez, I., Suarez-Hernando, O., Martínez-García, B.M., Larrasoaña, J.C. and Murelaga, X. 2016. First bird footprints from the lower Miocene Lerín Formation, Ebro Basin, Spain. Palaeontologia Electronica. 19.1.7A: 1-15, palaeo-electronica.org/content/2016/1417-early-miocene-bird-footprints

Doyle, P., Wood, J.L. and George, G.T. 2000. The shorebird ichnofacies: an example from the Miocene of southern Spain. Geological Magazine , Volume 137, Issue 5 , September 2000 , pp. 517 – 536, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756800004490.

Elbroch, M. and Marks, E. 2001. Bird Tracks and Sign: a guide to North American species. Published by Stackpole Books.

Erickson B R, 1967. Fossil bird tracks from Utah. Mus Observer, 5(1): 6-12.

Falk A R, Hasiotis S T, Martin L D, 2010. Feeding traces associated with bird tracks from the Lower Cretaceous Haman Formation, Republic of Korea. Palaios, 25: 730-74.

Falk, A.R., Lim, J-D. and Hasiotis, S.T. 2014. A behavioral analysis of fossil bird tracks from the Haman Formation (Republic of Korea) shows a nearly modern avian ecosystem. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 52, pp. 129-152.

Fang Y.-T., Tuanmu M.-N. and Hung C.-M. 2018. Asynchronous evolution of interdependent nest characters across the avian phylogeny. Nat. Commun.9, 1863. (doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04265-x.

Fernandez MS, Garcıa RA, Fiorelli L, Scolaro A, Salvador RB, et al. (2013) A Large Accumulation of Avian Eggs from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia (Argentina) Reveals a Novel Nesting Strategy in Mesozoic Birds. PLoS ONE 8(4): e61030. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0061030.

Fiorillo, A.R., Hasiotis, S.T., Kobayashi, Y., Breithaupt, B.H. and McCarthy, P.J. 2011. Bird tracks from the Upper Cretaceous Cantwell Formation of Denali National Park, Alaska, USA: a new perspective on ancient northern polar vertebrate biodiversity, Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 9:1, 33-49, DOI: 10.1080/14772019.2010.509356.

Fossilwiki website: bird ichnology (accessed December 2024).

Horner, J.R. 1984. The nesting behaviour of dinosaurs. Scientific American vol. 250, no. 4.

Hunt, A.P. and Lucas, S.G. 2007. Cenozoic vertebrate trace fossils of North America: Ichnofaunas, ichnofacies and biochronology. In: Lucas, Spielmann and Lockley, eds., 2007, Cenozoic Vertebrate Tracks and Traces. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 42.

Trace Fossils – KSU Ichnology website (Kansas State University), accessed January 2025.

Khoshyar, M., Abbassi, N. and Zohdi, A. 2016. Ichnology of the Gruiformes coastal bird footprint from Upper Red Formation (Miocene), Hesar region, west of the Zanjan Province. Conference paper.

Kim, J.Y., Lockley, M.G., Seo, S.J., Kim, K.S., Kim, S.H. and Baek, K.S. 2012. A Paradise of Mesozoic Birds: The World’s Richest and Most Diverse Cretaceous Bird Track Assemblage from the Early Cretaceous Haman Formation of the Gajin Tracksite, Jinju, Korea, Ichnos, 19:1-2, 28-42, DOI: 10.1080/10420940.2012.660414.

Kimitsuki, R., Zonneveld, J-P., Coutret, B., Rozanitis, K., Li, Y., Konhauser, K. and Gingras, M.K. 2024. Neoichnology of a Lake Margin in the Canadian Aspen Parkland Region, Cooking Lake, Alberta. Sedimentologika | 2024 | Issue 2 | eISSN 2813-415X.

King, M.R. 2015. Application of Ichnology Towards a Geological Understanding of the Ferron Sandstone in Central Utah. PhD. thesis. Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Alberta.

Krapovickas, V., Ciccioli, P.L., Mángano, M.G., Marsicanoa, C.A. and Limarino, C.O. 2009. Paleobiology and paleoecology of an arid–semiarid Miocene South American ichnofauna in anastomosed fluvial deposits. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 284 (2009) 129–152.

Lockley, M.G. and Harris, J.D. 2010. On the trail of early birds: a review of the fossil footprint record of avian morphological and behavioral evolution. In: Trends in Ornithology Research Editors: P. K. Ulrich and J. H. Willett, pp. 1-47.

Lockley, M.G., Lim, J-D., Kim, J.Y. , Kim, K.S., Huh, M. & Hwang, K-G. 2012. Tracking Korea’s Early Birds: A Review of Cretaceous Avian Ichnology and Its Implications for Evolution and Behavior, Ichnos, 19:1-2, 17-27, DOI: 10.1080/10420940.2012.660409.

Lockley, M.G., McCrea, R.T., Buckley, L.B., Lim, J.D., Matthews, N.A., Breithaupt, B.H., Houck, K.J., Gierliński, G.D., Surmik, D., Kim, K.S., Xing, L., Kong, D.Y., Cart, K., Martin, J. and Hadden, G. 2015. Theropod courtship: large scale physical evidence of display arenas and avian-like scrape ceremony behaviour by Cretaceous dinosaurs. Nature, Scientific Reports.

Lockley, M., Kim, M., K.S., Lim, J.D. and Romilio, A. 2021. Bird tracks from the Green River Formation (Eocene) of Utah: ichnotaxonomy, diversity, community structure and convergence, Historical Biology, 33:10, 2085-2102, DOI: 10.1080/08912963.2020.1771559.

Mainwaring M.C., Medina, I., Tobalske, B.W., Hartley, I.R., Varricchio, D.J., and Hauber, M.E. 2023 The evolution of nest site use and nest architecture in modern birds and their ancestors. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 378: 20220143.https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2022.0143.

Martin, A.J., Lowery, M., Hall, M., Vickers-Rich, P., Rich, T., Serrano-Brañas, C.I. and Swinkels, P. 2023. Earliest known Gondwanan bird tracks: Wonthaggi Formation (Early Cretaceous), Victoria, Australia. PLoS ONE 18(11): e0293308. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293308.

Milàn .J, Loope D.B. and Bromley R.G. (2008) Crouching theropod and Navahopus sauropodomorph tracks from the Early Jurassic Navajo Sandstone of USA. Acta Palaeontol Pol 53: 197–205.

Milner, A.R., Harris, J.D., Lockley, M.G., Kirkland, J.I. and Matthews, N.A. 2009. Bird-Like Anatomy, Posture, and Behavior Revealed by an Early Jurassic Theropod Dinosaur Resting Trace. PLoS ONE 4(3): e4591. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0004591.

Moussa, M. 1968. Fossil tracks from the Green River Formation (Eocene) near Soldier Summit, Utah. Journal of Palaeontology.

Mustoe, G.E. 2002. Eocene Bird, Reptile, and Mammal Tracks from the Chuckanut Formation, Northwest Washington. Palaios, 2002, V. 17, p. 403–413.

Noad, J. 2005. Mysterious mangroves. Rock Watch Magazine, issue 40, pp. 4 to 5.

Noad, J.J. 2013. The Power of Palaeocurrents: reconstructing the palaeogeography and sediment flux patterns of the Miocene Sandakan Formation of eastern Sabah. Indonesian Journal of Sedimentary Geology, 28: pp. 31-40.

Noad, Jon. 2017. Making sense of swamps: integrating fossils with sedimentology. In: 52 More Things You Should Know About Palaeontology. Published by Agile Libre.

Padia, D., Desai, B., Chauhan, S. and Vaghela, B. 2024. Discovery of fossil avian footprints from Late Holocene sediments of Allahbund uplift in Great Rann of Kachchh of Western India. Nature Scientific Reports (2024), 14:31506 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83210-z.

Paik, I.S., Lee, Y.I, Kim, H.J. and Huh, M. 2012. Time, Space and Structure on the Korea Cretaceous Dinosaur Coast: Cretaceous Stratigraphy, Geochronology, and Paleoenvironments, Ichnos, 19:1-2, 6-16, 10.1080/10420940.2012.660404.

Payros, A., Astibia, H., Cearreta, A., Suberbiola, X.P., Murelaga, X. and Badiola, A. 2000. The Upper Eocene South Pyrenean Coastal deposits (Liedena sandstone, navarre): Sedimentary facies, benthic formanifera and avian ichnology. Facies 42(1), 107-132, DOI: 10.1007/BF02562569.

De Raaf, J.F.M., Beets, C. and van der Sluis, G.K. 1965. Lower Oligocene bird tracks from northern Spain. Nature July 10, 1965.

Rigby, J.K. 1968. Guide to the Geology and Scenery of Spanish Fork Canyon Along U. S. Highways 50 and 6 Through the Southern Wasatch Mountains, Utah. Brigham Young University Geology Studies Volume 15 – 1968. Part 3, Studies for Students No. 2.

Roberts, G. 2009. Ephemeral, Subfossil Mammalian, Avian and Hominid Footprints within Flandrian Sediment Exposures at Formby Point, Sefton Coast, North West England, Ichnos, 16:1-2, 33-48, DOI: 10.1080/10420940802470730.

Swennen C. and Yu, Y .T. 2005. Food and feeding behavior of the black-faced spoonbill. Waterbirds, 28(1): 19-27.

De Valais, S. and Melchor, R.N. 2008. Ichnotaxonomy of Bird-Like Footprints: An Example from the Late Triassic-Early Jurassic of Northwest Argentina. Journal of Verterbrate Paleontology 28(1):145-159.

Bird ichnology, Wikipedia, accessed January 2025.

Zonneveld, J.-P., Zaim, Y., Rizal, Y., Ciochon, R. L., Bettis III, E. A., Aswan & Gunnell, G. F. 2011. Oligocene Shorebird Footprints, Kandi, Ombilin Basin, Sumatra, Ichnos, 18:4, 221-227, DOI: 10.1080/10420940.2011.634288.

Zonneveld, J-P., Zaim, Y., Rizal, Y., Aswan, A., Ciochon, R.L., Smith, T., Head, J., Wilf, P. and Bloch, J.J. Avian foraging on an intertidal mudflat succession in the Eocene Tanjung Formation, Asem Asem Basin, south Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo. Palaios, 2024a, v. 39, 67–9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2110/palo.2023.004.