This blog post is part of our series: “A day in the life of a geomorphologist” for which we’re accepting contributions! Please contact one of the GM blog editors, Emily or Emma, if you’d like to contribute on this topic, or others.

by Emily Bamber, PhD Student, University of Texas at Austin

Twitter: @Bambi_in_Space | email: emily.bamber@utexas.edu

A Day in the Life of Geomorphologists in Paradise

In writing about “A day in the life of a geomorphologist”, should I have picked an average day? Maybe. But instead, here’s a very unrepresentative snippet of geomorphology from field work in Cape Verde. I was lucky enough to be invited to fieldwork by Dr. Gaia Stucky de Quay, Dr. Ricardo Ramalho, and Dr. Shasta Marrero who are investigating the geomorphology of basaltic island terrains for a better understanding of the islands’ histories, as well as applications of these locales as Mars analogue terrains. Here’s an excerpt from the field diaries mid-way through our trip, on the Island of Santiago, where Ricardo led us on a trip to see and sample mega-tsunami transported boulders!

7am: I take a refreshing morning swim in the balmy tropical Atlantic. This is a very important aspect of the day because I don’t consume caffeine, and the swim also allows me to wake up and appreciate the coastal processes at work on the island which make it a haven for turtles and tropical fish (snorkel recommended).

9am: After a hearty breakfast of fresh fruits, breads and everyone else’s necessary coffee hit, we hit the winding roads along the coast and drive up through the mountains on the North side of Santiago Island. A short hike up and down dusty valleys brings us to a boulder of submarine basalt perched on the ~300m high clifftop plateau. Further along, we reach a boulder of marine carbonate (Ricardo knows the locations of each boulder like the back of his hand). We’re walking on top of younger subaerial basaltic lava flows, which means something transported these boulders up and onto the cliff top, from meters below!

11am: At a large boulder we pause to take a sample for cosmogenic exposure age dating led by Shasta and Ricardo. Many many photos are taken, a 3D model is constructed using the latest iPhone LiDAR camera, a phone app (compass-clino) is used to make topographic shielding measurements, and an angle grinder is deployed to make a lot of dust and a hole at the top of the rock (on the least eroded surface). This is high-tech cosmo sampling in contrast to my own study site (where the equipment didn’t make it to the connecting flight, and we relied on sledgehammer alone — another story for another day). The drone even gets an outing for some aerial photography of the boulders on the cliff top, and the stratigraphy of the cliff reveals the boulder source regions some tens of meters below us. Curious…

1pm: After sampling a handful of boulders among this large scattered field of boulders (of varying lithology!), we are tramping back to the car when we come across “The mothership”, a giant bus-sized boulder of submarine basalt perched on the surface. It’s taller than the trees around us, and how did it get here? It’s not actually an alien mothership. It was transported by a mega-tsunami wave, which was generated when the flank of the nearby volcanic island, Fogo, collapsed into the ocean and displaced massive amounts of water. Floored by the thought, we sit and eat extremely well heated/melted sandwiches and snacks while we consider the height of that wave crashing towards us, hungry for destruction, much like our own stomachs right now.

The “mothership” tsunami-transported huge boulder of submarine basalt on the clifftop plateau (Featuring Ricardo, Gaia and Emily for scale). Credit: Shasta

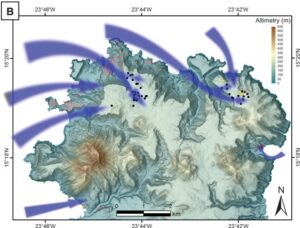

2pm: The hike and car ride to the next location is quiet and contemplative as we digest the size of that tsunami wave, or maybe because we’re just digesting our way out of our food and heat induced sleepiness. But this is fieldwork, not a holiday (despite the tropical island setting… not to brag). We reach the next boulder field, the next valley along. The location of two boulder fields, one on each side of the valley, suggest the direction of the wave. Here, we see more giant car sized boulders on the plateau and in the valley which have been plucked from cliff faces and from a knick point and transported UP-stream. Standing at the edge of the valley looking out towards the ocean really gives us a chilling sense of that immense wave rushing towards the landscape in the geological past. It’s so terrifying to think about, that maybe I’ll never swim in the ocean again.

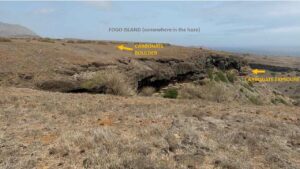

The carbonate originates from tens of meters below, in the cliff (which is ~300m high above sea level), so waves at least 300m high must have transported the boulder.

Photo from Ramalho et al. (2015), showing the view from the Santiago cliff tops towards Fogo Island, from where the Tsunami originated. The cliff heights give the viewer a sense of the scale of the wave!

Figure from Ramalho et al. (2015), showing the tsunami boulder distributions and their link to tsunami flow around the island, caused by the collapse of the flank of Fogo island.

4pm: After an exhausting day in the heat, we return to the hotel and pop down to the beach to wash off the copious amounts of dust with a quick swim and snorkel, followed by a delicious Cape Verdean dinner. A good night’s sleep is needed (and goes relatively unplagued by tsunami nightmares), before another “hard” day in the field tomorrow!

Disclaimer: This was one of the most exciting days of our field trip we actually spent a lot of time digging up and sorting through river sediments and getting incredibly dusty in a hot, dry environment (not that that’s not exciting for geomorphologists, but, it’s not quite as fun to write about).

Interested in this work? You can learn more about the evidence for Tsunamis in the Cape Verdean Islands in the reading below. If you’re interested in cosmogenic sampling, I produced a video ‘how to’ on the methods involved in sampling which you can see here.

Did you enjoy this blog post? This blog post is part of our series: “A day in the life of a geomorphologist” for which we’re accepting contributions! Please contact one of the GM blog editors, Emily or Emma, if you’d like to contribute.

Further Reading

Ramalho, R. S., Winckler, G., Madeira, J., Helffrich, G. R., Hipólito, A., Quartau, R., Adena, K., & Schaefer, J. M. (2015). Hazard potential of volcanic flank collapses raised by new megatsunami evidence. Science Advances, 1(9), e1500456.

Barrett, R., Lebas, E., Ramalho, R., Klaucke, I., Kutterolf, S., Klügel, A., Lindhorst, K., Gross, F., & Krastel, S. (2020). Revisiting the tsunamigenic volcanic flank collapse of Fogo Island in the Cape Verdes, offshore West Africa. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 500(1), 13–26.

Costa, P. J. M., Dawson, S., Ramalho, R. S., Engel, M., Dourado, F., Bosnic, I., & Andrade, C. (2021). A review on onshore tsunami deposits along the Atlantic coasts. Earth-Science Reviews, 212, 103441.

Peter Stanley

Fascinating, my brother-in-laws family hails from Cape Verde. Have known the islands as whaling stations & for slave trading. I’ll enjoy telling him about the megatsunami, he’ll be enthralled.

emmalodes

So cool that you have a personal connection to such a fascinating place!