One feature stands out in any map of tropical rainfall from satellites: a narrow band of intense precipitation encircling the globe near the equator. This is the Intertropical Convergence Zone, a key feature of the global atmospheric circulation that imports moisture into the tropics and exports energy to higher latitudes. But for decades, climate models have struggled to simulate this feature correctly: Many stubbornly produce an error known as the double Intertropical Convergence Zone bias, in which an unrealistic second rain band appears south of the equator year round, especially over the Pacific Ocean. This artificial band affects global energy redistribution, the behavior of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation and the evolution of sea surface temperatures with climate change.

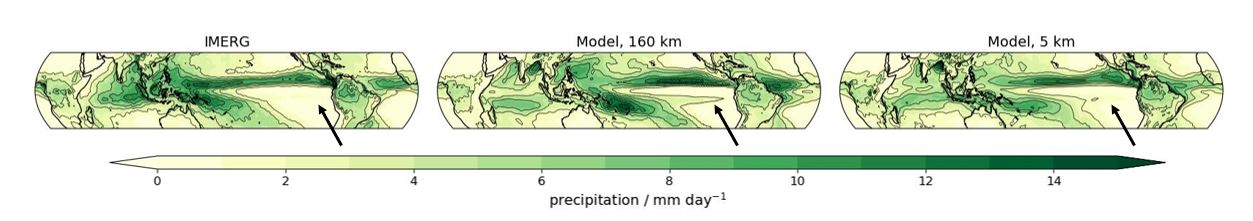

In our recent study, we examined this problem using the ICON atmosphere model, running simulations from conventional 160 km resolution all the way up to 5 km grid spacing (storm resolving), where deep convection begins to be represented by explicit physics. A natural question motivates this hierarchy: Does increasing resolution finally eliminate the double Intertropical Convergence Zone?

Surprisingly, it does not (Fig. 1). The bias weakens in places, but the core problem persists at every resolution. This finding points to a cause originating in still smaller-scale processes. In fact, our analysis suggests that the root of the double Intertropical Convergence Zone bias sits upstream of the deep tropics, in the subtropics, where the atmosphere picks up much of the moisture that later fuels equatorial rainfall.

Fig. 1: Observed tropical rainfall (IMERG data product) and simulated tropical rainfall at 160 km and 5 km model resolution. Figure adapted from Kroll et al. 2025.

What storm-resolving resolution improves — and what it does not

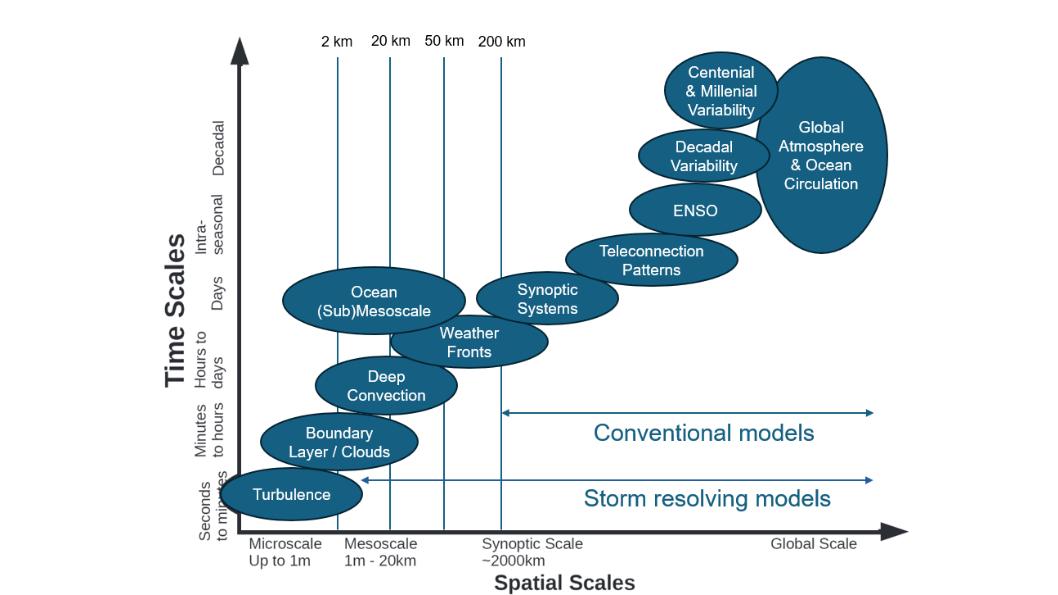

As models become more detailed, they resolve more of the fine-scale motions that govern cloud formation. This reduces biases, for example by improving the representation of subdaily rainfall extremes. Certain empirical parameterizations can be discarded, because more scales can be resolved explicitly. But even at 5 km resolution, essential parts of the atmosphere remain unresolved, amongst them: turbulence and shallow convection (Fig. 2). These processes operate at scales smaller than 5 km. They must still be parameterized — and they play a crucial role in exporting moisture upward out of the boundary layer.

This is the key insight: even if the model can start to simulate the structure of the largest thunderstorms, the supply of moisture feeding those storms can still be wrong. And if that moisture supply is disrupted in the subtropics, resolution alone can not repair the resulting rainfall patterns.

Fig. 2: Schematic diagram displaying interacting spatial and temporal scales relevant to regional climate change information. The processes captured at different temporal and spatial scales are indicated as a function of these scales. Figure adapted from Franzke et al., 2020 (https://doi.org/10.1029/2019RG000657).

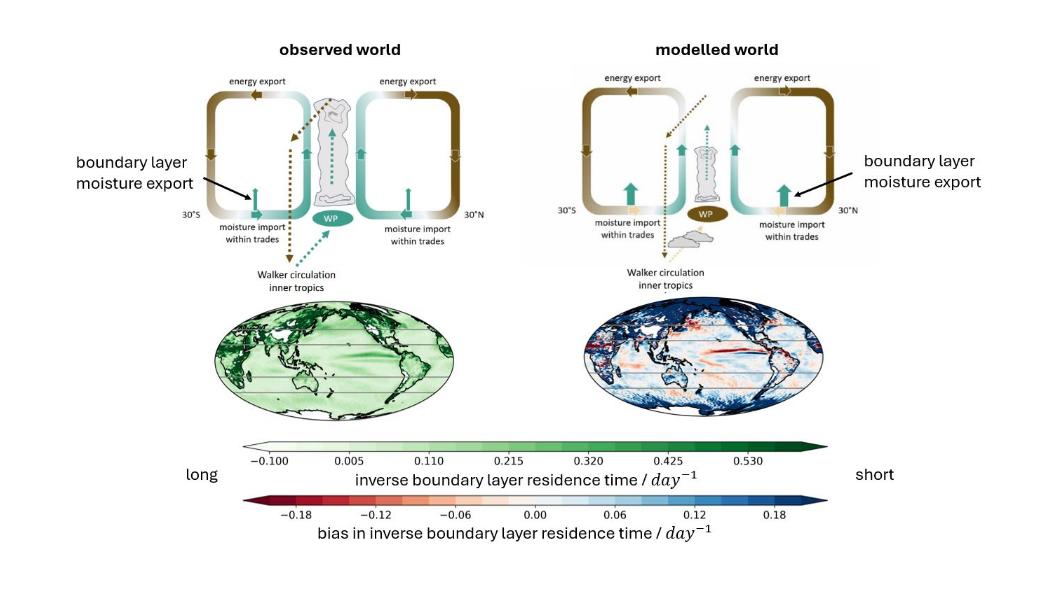

A moisture “”leak” in the subtropics

In the real atmosphere, a large fraction of the water vapour that fuels tropical convection has its origin in the subtropics. This moisture is carried toward the equator near the surface by the trade winds. In our model, we found that this low-level moisture does not always complete the journey (Fig. 3). The culprit is a combination of the model’s turbulence and shallow convection parameterizations, which transport moisture upward too aggressively. As a result, much of the subtropical moisture that should flow horizontally toward the equator instead gets lifted prematurely into the free troposphere. The near-surface air arriving at the equator is therefore too dry, particularly over the warm waters of the West Pacific.

Deep convection in this region weakens because of insufficient moisture, and the entire Pacific Walker circulation slows down. This change allows spurious convection to develop in the East Pacific, precisely where the artificial second rain band usually forms. In this way, a bias in subtropical moisture pathways cascades into a well-known tropical rainfall problem.

Fig. 3: First row: Conceptual depiction of the main zonal and meridional circulations exchanging moisture and energy between the subtropics and the tropics as observed and simulated. Observations show that the moisture within the innermost tropics originates from evaporation in tropical and subtropical areas. The moisture is imported into the innermost tropics by the trade winds, with small losses to the free troposphere. In the innermost tropics it is then transported to the main convective regions, i.e., the Warm Pool (WP) within the zonally anomalous Walker circulation. Energy is exported to the subtropics within the outward branches of the Hadley circulation. In conventional simulations, a large portion of the subtropical moisture is lost due to too much vertical transport of moisture from the boundary layer to the free troposphere. This leads to a moisture deficit in the tropics, specifically over the WP, reducing deep convection, slowing down the Walker circulation and leading to spurious additional convective centers over the Eastern Pacific as too little moisture is transported to the WP within the boundary layer. Green colors indicate high moisture content. Brown colors low moisture content. Second row: Inverse residence time within the boundary layer as observed, and with simulated bias against observations. The gray lines mark the 40 degree and 20 degree latitudes. Figure adapted from Kroll et al. 2025.

Why removing parameterizations may not be the solution at storm resolving resolution

It may seem tempting to remove the parameterizations that handle vertical moisture transport, especially when they appear to be responsible for exporting moisture too vigorously. We tested disabling deep convective and non-orographic gravity wave parameterizations in the 5-km configuration. However, because turbulence and shallow convection occur at still smaller scales, parameterizations of these processes remained.

The result was not an improvement. Many of the large-scale biases remained, the atmospheric boundary layer dried even more, and the structure of the Intertropical Convergence Zone did not become more realistic. This shows that discarding parameterizations does not necessarily push the model toward physical consistency — premature discard of parameterizations can make existing model shortcomings even more evident.

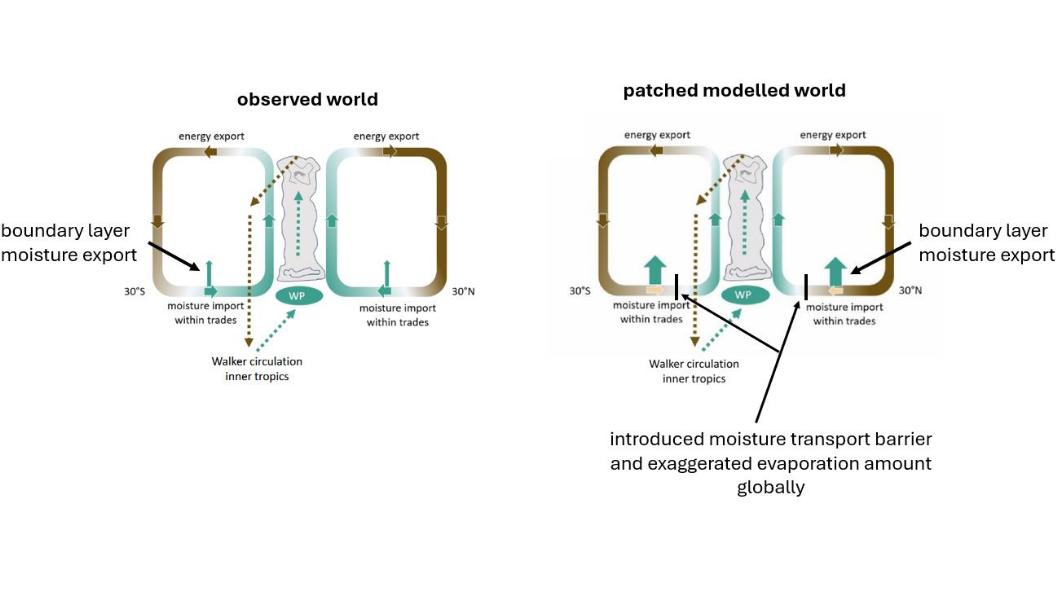

A tempting patch that treats the symptoms, not the cause

We also tested a suggested tuning approach: increasing the minimum wind speed used to determine turbulent exchange with the surface. This change enhances evaporation. The immediate effect is encouraging — more evaporation leads to moister near-surface air, stronger convection, and a more realistic Intertropical Convergence Zone.

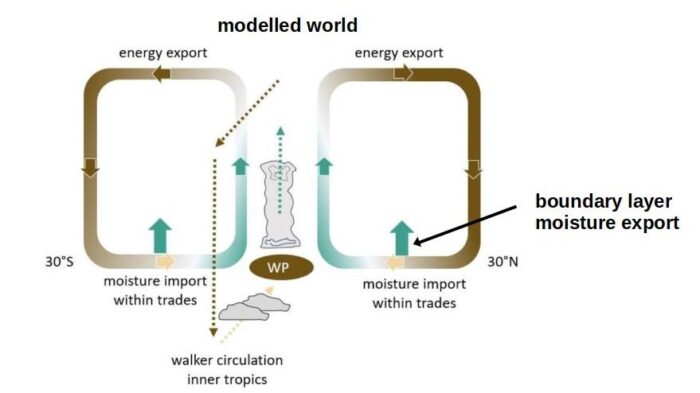

Yet this solution comes with side effects (Fig. 4). Increasing the minimum wind speed deteriorates the representation of the trade winds, alters the origin of moisture entering the tropics, and compromises important feedback loops between the tropics and extratropics. It creates a simulation that looks more correct but behaves less consistently with physical expectations. This illustrates a broader challenge in climate modelling: improvements must be physically consistent, not just aesthetically pleasing.

Fig. 4: Conceptual depiction of the main tropical circulations exchanging moisture and energy between the subtropics and the tropics as observed and in the patched simulations. The observational depiction is identical to Figure 3. In the patched simulations increased evaporation leads to an additional moisture source in the tropics, which resolves the dry bias over the WP. However, the adjustments increase the positive free-tropospheric moisture bias between 0 degree to 30 degree, reduce the trade wind strength and change the balance between innermost-tropical and subtropical sources of tropical moisture content. Green colors indicate high moisture content. Brown colors low moisture content. Figure adapted from Kroll et al. 2025.

The broader lesson: The earth system is interconnected and the subtropics influence the tropics

Our work shows that the double Intertropical Convergence Zone bias is not simply a tropical rainfall problem. This bias can arise from moisture transport problems rooted in how the model handles processes in the subtropics. If turbulence and shallow convection parameterizations export moisture upward too quickly, the tropics never receive the low-level moisture they need — and the entire circulation adjusts in unrealistic ways.

Increasing resolution to km-scale alone cannot fix this, because the unresolved processes responsible for the bias remain parameterized, even at the highest currently feasible global resolutions. As such, removing parameterizations or tuning single parameters in isolation can give the right answer for the wrong reasons.

Further progress on this problem requires pushing for even higher resolution, improving the physically based representation of subtropical moisture transport and ensuring that parameterizations remain robust across the full range of model resolutions. Only by accurately simulating the moisture pathways upstream can we expect the tropical rainfall distribution to fall into place in a way that is physically consistent.

To dive deeper into the research, you can read the full open-access article here.

More information on high-resolution simulations are given in this BBC tech news broadcast, which also features Clarissa Kroll showcasing the simulations analyzed in this study.

This post has been edited by the editorial board.

References Kroll, C. A., Jnglin Wills, R. C., Kornblueh, L., Niemeier, U., and Schneidereit, A.: Parameterization adaption needed to unlock the benefits of increased resolution for the ITCZ in ICON, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 25, 16915–16943, , 2025. DOI: 10.5194/acp-25-16915-2025