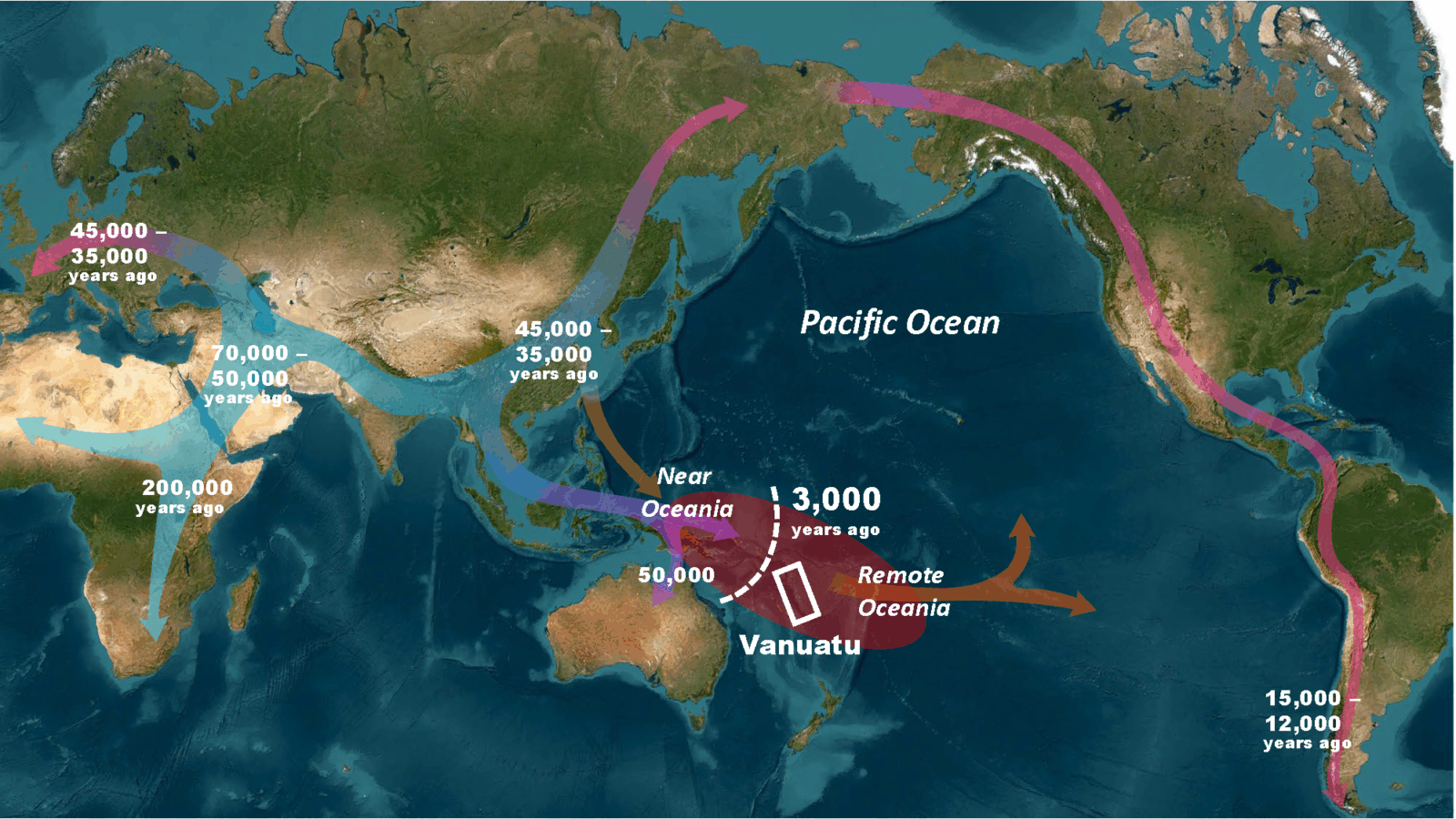

The Pacific Ocean is a vast expanse that is punctuated by diverse islands and archipelagos. Some of these islands closer to Asia and the Australian landmass have been home to humans for tens of millennia. Others – spread across Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia – make up Remote Oceania and were only settled by humans within the past few thousand years. Archeological investigations have provided valuable insights into the history of human settlement of Remote Oceania, but much remains unknown about these early settlers. Key questions remain about the exact timing of human arrival at different sites in Remote Oceania, the ways people fed themselves, and the climatic context for migration.

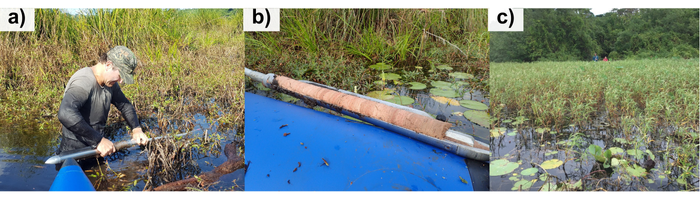

In 2017, we travelled to Vanuatu (Figure 1) to collect sediment cores from lakes and swamps from several islands in the archipelago with the aim of learning more about the early settlers. We were able to recover a 4 meters section of mud from Emaotfer Swamp on the island of Efate (Figure 2). Emaotfer is a particularly exciting site to conduct sedimentological research, as it is located adjacent to the Teouma Cemetery, one of the most important archeological sites from the Lapita culture, considered the earliest group to reach Remote Oceania.

Figure 1. Past Human migrations. The dashed line indicates the boundary between Near Oceania and Remote Oceania. The red shaded area represents the Lapita cultural complex, where archaeological remains of the Lapita culture have been found. The white rectangle marks the location of Vanuatu in the Pacific. Modified from National Geographic https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/global-human-journey/

Figure 2. Fieldwork in Vanuatu. a) Dr. Matiu Preble using a Russian peat corer in the Emaotfer swamp on the island of Efate. b) A view of the Emaotfer pond. c) A section of the peat core retrieved from the swamp. Pictures 2A and 2C were taken by Nathalie Dubois, 2B by Nemiah Ladd.

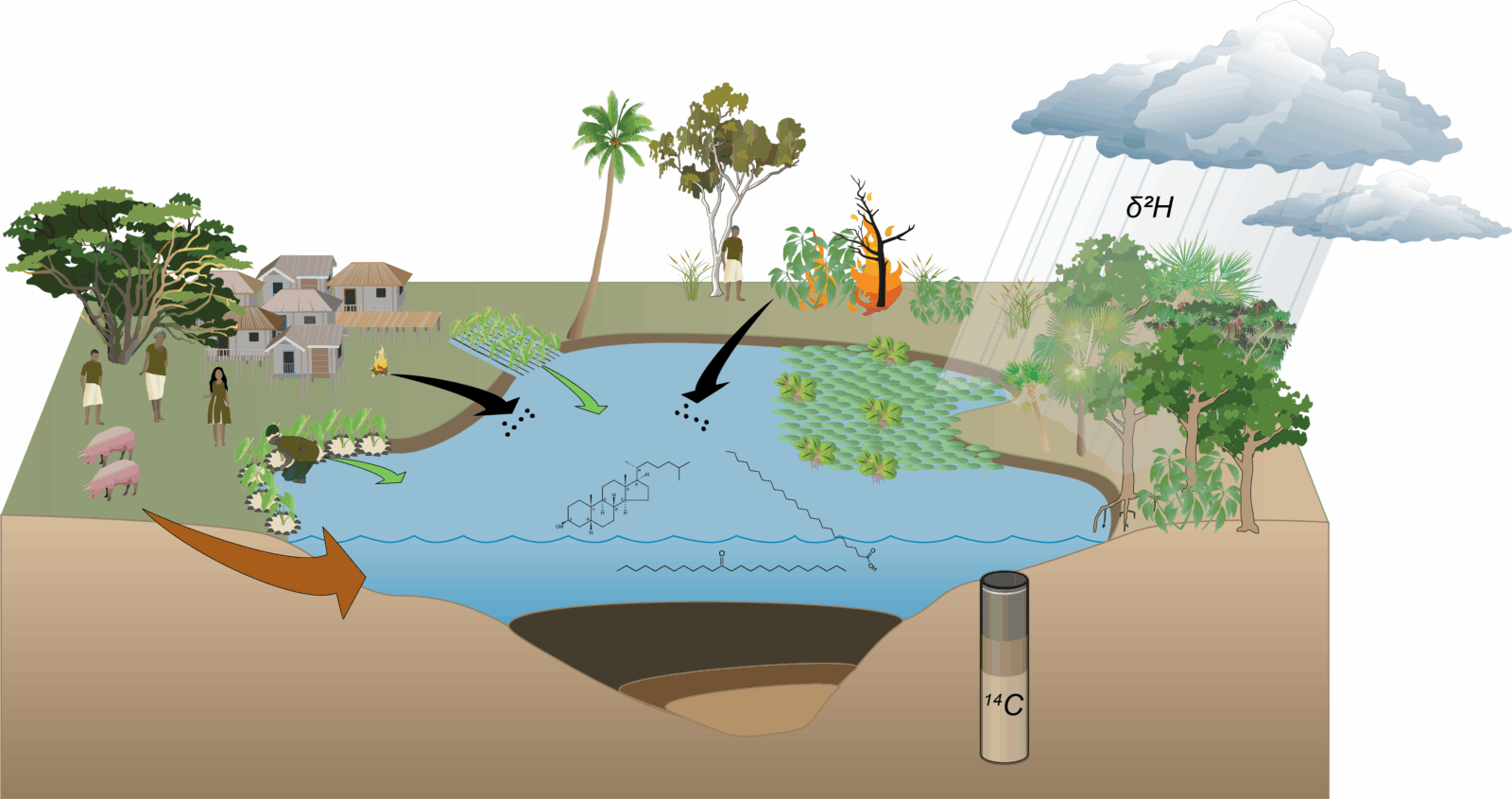

We carefully isolated 57 plant fragments from different layer in the core and used radiocarbon dating to develop of robust model for how old the different layers were (Figure 3). We then analyzed the chemical composition of the sediment and quantified specific molecules that are only produced in the digestive tracts of omnivores – in this context, humans and the pigs they introduced. We were able to use the initial presence of these fecal molecules to narrow down the exact arrival of the Lapita in this part of Vanuatu to 2,739 – 2,879 years before present. In the same layers where we found the first signs of human waste, we also found molecular evidence of what those humans had been eating – taro. Taro is a root vegetable and a stable crop throughout the tropical Pacific today. In our study, we were able to show that it was brought by initial settlers and cultivated, likely forming a key component of their diet.

Figure 3. A schematic landscape of Vanuatu depicting some of the signals that can be transported and preserved in the sediment. Fecal markers, indicating the presence of human and pigs, palmitone as a proxy specific for taro, charcoal as a proxy for burning. The combination of these proxies is used as indication of human presence. Figure from Camperio, 2024, PhD Thesis.

We also wanted to know about the hydroclimate conditions when people migrated – was it a time of drought that pushed them to explore? Or was it easier to establish new communities during relatively wetter periods that favored horticulture? To answer this question, we looked for clues in the amount of two different types of hydrogen (isotopes) that are incorporated into plant material that accumulates in sediment. We saw that there was relatively less of the heavy form of hydrogen in plant waxes during the period of Lapita settlement on Efate. This pattern is consistent with relatively wet conditions, and suggest that expansion occurred during times when it was easier to cultivate new crops. These results were recently published in Communications Earth & Environment, and demonstrate the importance of precipitation patterns in determining when humans travelled to remote islands, and the resource-acquisition strategies they used upon arrival.

This post has been edited by the editorial board.

References Camperio, G., Ladd, S. N., Prebble, M., Welte, C., Kumar, K., & Kotra, N. D. (2024). Bomb pulse dating in Vanuatu tracks past extreme events in areas lacking instrumental records. Sedimentary biomarkers reveal the legacy of human-climate interactions in Vanuatu, 27. Camperio, G., Ladd, S.N., Prebble, M. et al. (2024). Sedimentary biomarkers of human presence and taro cultivation reveal early horticulture in Remote Oceania. Commun Earth Environ 5, 667. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01831-8