Few places in the world conjure up images of remoteness and harshness like Far Eastern Siberia. Yet, it’s places like these where our science is needed most.

Arctic soils hold vast amount of carbon, protected in thick layers of permafrost, but these stores are becoming more and more vulnerable as temperatures in the Arctic warm, and are set to warm faster than anywhere else on the planet. Recent studies have further suggested that the freezing and thawing activity in permafrost areas plays a crucial role in the overall carbon balance of these regions, trapping and releasing large quantities of gas in unfrozen, still active soil layers during the shoulder seasons (e.g. Zona et al., 2016). Hence the challenge to measure C fluxes in these regions during the early spring and late autumn periods either side of the snow-free growing season.

However, just getting to these sites is often a challenge, both logistically and personally!

I recently travelled to Siberia in April with my boss to set up eddy covariance instrumentation at our Arctic Siberian field site – Kytalyk nature reserve, about 30 km northwest of Chokurdakh, a small town itself a three-and-a-half-hour flight (on a plane that was two generations older than me) northwest of Yakutsk in the Sakha Republic of Russia. Our research group, led by Prof. Han Dolman at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, has been measuring carbon fluxes at the site since 2003. This year I took on the reigns of these measurements, a long way from my home country of New Zealand, and it was more challenging than I expected…

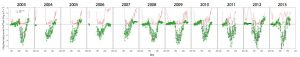

Our long-term record of CO2 fluxes from the Kylalyk site in Arctic Siberia, one of just a handful of such “lookout posts” in the vulnerable Arctic (photo credit: Luca Belelli Marchesini).

During my interview for this position, I was asked to respond to a riddle:

“You are in the field with a team of Russians, they have been drinking vodka and are very drunk. An emergency arises, and you need to get everyone to safety. What do you do?”

Whilst carefully refraining from explaining that if everyone else was drinking vodka, I probably would have been too, I managed to find an answer that must have been acceptable because I got the job. This question was just a taster for the unique encounters you can experience while doing fieldwork in new and wonderful places.

Siberian Russia is not the most culturally divergent place from what I am accustomed to, and I’m sure there are many readers who have been to more wild regions and eaten more outrageous cuisine. But I wanted to share some of my experiences for those of you who may have to follow a similar path involving cultural and culinary experiences that you might otherwise not seek out in your daily life.

I’m not a big fan of fish, for instance, certainly not raw fish. Raw fish happens to be the go-to protein dish in this part of Siberia. A particular treat is the Indigirka Salad, cubes of frozen raw fish and onions – the ultimate challenge for any breath freshener.

I was also to enjoy boiled tongue (I’m not sure whose) in creamy, custard-like sauce, and soup made primarily from cow stomach and entrails. It smelt as bad as it sounds, something like a cross between cow burps and a pig’s fart, and the meat looked exceptionally disturbing.

Out at the field site I would eat plenty more frozen fish, but cut directly from the fish itself and dipped in instant noodle flavouring. This was quite tasty if you ate it fast enough not to notice the texture of raw fish melting in your mouth. I would also drink fermented horse milk, and eat jelly made from bone marrow. A cube of the latter is enough to make you see your breakfast again under the right circumstances, unless you have vodka to wash it down.

My advice here? Don’t be afraid to try new things, but don’t be afraid to say no if it tastes like an unwashed cow’s anus and vomiting isn’t high on your agenda for the day.

Taking a sled ride behind a snowmobile as we headed into the remote and snowy Arctic was also an amazing experience, but after an hour of riding in a sled with no suspension, the majority of your bones will eventually turn into a fine powder, as shown here.

During our stay in the field we celebrated Koningsdag, the Dutch King’s Birthday (27th April – also my birthday, though I didn’t convince anyone that I was royalty), by flying a Dutch flag over a small piece of the Russian Arctic (this was not meant as an act of geopolitical aggression).

Definitely not conquering the Russian Arctic, Joshua Dean on the left, Han Dolman on the right, with the (not yet working) eddy covariance tower in the background (photo credit: Joshua F. Dean).

At the site, setting up the eddy covariance tower proved to be relatively straight forward. However, we first found that we weren’t collecting data from the sonic anemometer (measuring wind speed and direction in three-dimensions). It turns out we hadn’t turned it on (duh!) leading to the discovery that the solar panels and batteries weren’t working. Some MacGyver-like electrical combos later and we had the system up and running. Success! But a good example of how inventive you have to be to fix things when backup gear is literally half a world away.

Back in Yakutsk we relaxed with a banya (a Russian Sauna), which includes plenty of beer, hanging out naked with your boss, and a thorough birch branch whipping by a 60-something Russian professor.

The generosity of our Russian hosts was unsurpassed. While the food certainly pushed some of my culinary boundaries, I’m pretty sure our hosts found my myriad reactions to their food and drink highly amusing. I look forward to visiting again in the summer for more fieldwork, and to strengthen the bond of social and scientific collaboration that started with a mouthful of cow guts.

Reference: Zona, D. et al. (2016) Cold season emissions dominate the Arctic tundra methane budget. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113(1):40-45.

Dr. Joshua F. Dean from the VU University Amsterdam wrote this blogpost. He is a postdoctoral researcher who explores the carbon cycle in the Arctic and temperate peatlands to determine methane and carbon dioxide feedbacks under a warming climate. His work involves experimental approaches, modelling, and direct and indirect measurements of carbon dioxide and methane emissions from freshwater environments, with fieldwork campaigns throughout the Arctic and northern hemisphere peatlands.

Pingback: Biogeosciences | What´s in your fieldbag? Part 1: measuring freshwater carbon fluxes in the Artic