Marine low clouds, such as stratocumulus, play a central role in regulating Earth’s climate by reflecting incoming sunlight back to space. Yet these clouds are notoriously difficult to simulate and predict. One reason is that their evolution depends strongly on the surrounding atmosphere: temperature structure, moisture, winds, and aerosols all interact in complex ways. As a result, cloud responses seen in one situation may not apply to another.

A common challenge in the study of clouds is that observations often capture only snapshots, while models are tested under a limited number of idealized conditions. This makes it difficult to assess whether a given cloud response is robust across the range of environments that occur in the real world.

Rather than sampling the atmosphere at fixed locations, air parcels are tracked as they move with the flow, allowing us to study cloud evolution in a “Lagrangian framework” that is more consistent with how clouds actually develop.

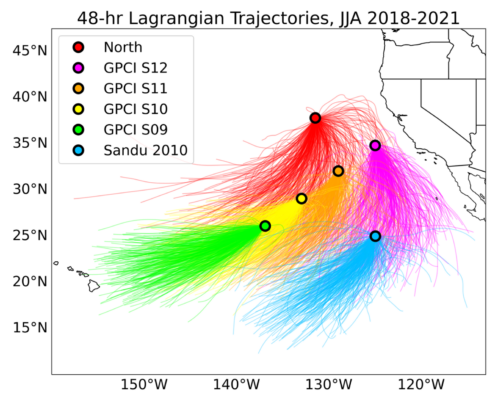

Using reanalysis winds and satellite observations, more than 2200 48-hour trajectories were generated within the stratocumulus cloud deck of the Northeast Pacific during summer from 2018 to 2021. Each trajectory represents the history of an air mass moving through a marine cloud environment, carrying with it information about temperature, humidity, aerosols, and cloud properties.

Left: Example satellite snapshot of clouds over the Northeast Pacific Ocean. Right: Example of a 48-h Lagrangian trajectory in the same region, initialized on the same day (from the paper). As air masses move from offshore of California toward Hawaii, cloud morphology transitions from solid stratus to open- or closed-cell stratocumulus and eventually to shallow cumulus. Satellite imagery from the NASA Worldview website (last accessed 2 Feb 2026): https://worldview.earthdata.nasa.gov/

To investigate this large dataset, we focused on a set of key environmental variables known to control marine cloud behavior, such as stability of the atmosphere where the clouds form, the amount of moisture in the air above the clouds, the surface wind speed and the vertical motion (subsidence rate) of air above the clouds. We applied a statistical technique, called principal component analysis that reduces the complexity of the dataset while preserving its dominant patterns of variability.

Findings:

This analysis revealed that much of the diversity in cloud-controlling conditions can be captured by just of variation (the first two principal components from PCA), where each mode is defined by a combination of specific environmental factors. Importantly, this simplification allowed us to identify a small subset of trajectories that collectively represent the full range of observed environmental conditions. In other words, instead of running computationally expensive models for thousands of cases, researchers can focus on a few dozen selected trajectories that still span realistic cloud and aerosol variability.

Why does this matter? High-resolution cloud models, such as large-eddy simulations, are powerful tools for studying cloud processes, but they are too expensive to run for every possible scenario. By linking these models to a representative set of observed trajectories, we can test how clouds respond to environmental and aerosol perturbations under conditions that actually occur in nature.

To demonstrate this, we selected two contrasting trajectories from the library and used them to initialize two-day, high-resolution simulations. One case featured precipitation and showed how interactions between rainfall and aerosols can accelerate cloud breakup. The other case did not precipitate and followed a more gradual cloud thinning driven by warming of the surface ocean and mixing of dry tropospheric air to boundary layer. These examples highlight how cloud responses depend strongly on the underlying environment.

This study provides a community resource. The trajectory library can be used to evaluate cloud models, explore aerosol–cloud interactions, and test proposed climate intervention strategies such as marine cloud brightening under realistic conditions. Marine clouds remain one of the largest sources of uncertainty in climate projections. Approaches that bridge observations and models, and that explicitly account for environmental variability, are essential for reducing that uncertainty. We hope this trajectory-based framework will help move the field in that direction.

Reference:

Erfani, E., Wood, R., Blossey, P., Doherty, S., & Eastman, R. (2025). Building a comprehensive library of observed Lagrangian trajectories for testing modeled cloud evolution, aerosol–cloud interactions, and marine cloud brightening. Atmos. Chem. Phys., 25, 8743-8768, doi: 10.5194/acp-25-8743-2025.

The basic model for tracking clouds and observational dataset used are available for use on zenodo.