Around the world, the most vulnerable, marginalized, and racialized are disproportionately impacted by a variety of environmental stressors such as extreme heat, health-harming air pollution, and the growing impacts of climate change. In the United States, research has uncovered how Black and Brown communities and those with lower socioeconomic status are exposed to higher concentrations of many air pollutants. One such pollutant, nitrogen dioxide or NO2, is primarily produced by traffic and industry in urban areas. Millions of new pediatric asthma cases are thought to be caused by NO2 pollution every year, and NO2 can aid in the formation of fine particulate matter, which has been causally linked to a number of adverse health impacts.

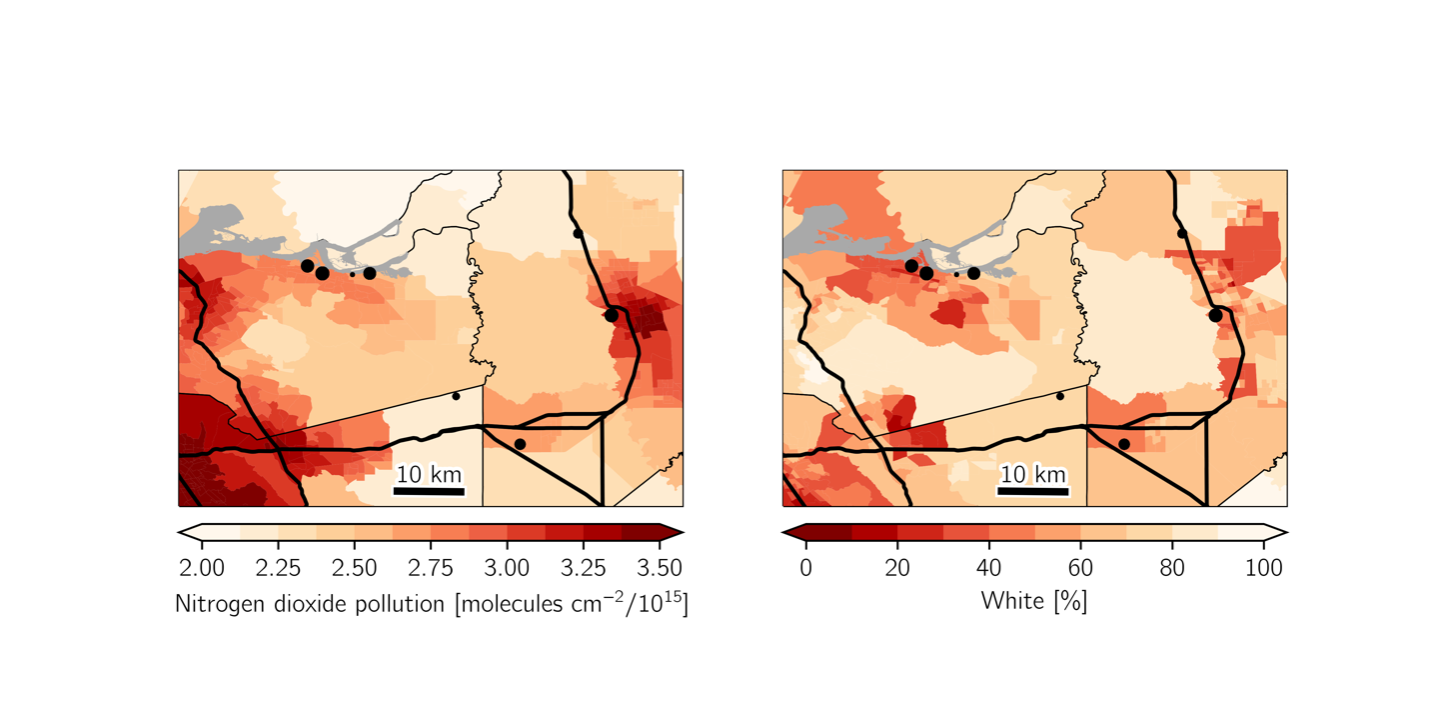

The recently-launched TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) aboard the European Space Agency’s Sentinel 5P satellite measures NO2 and other health- and climate-relevant gases in the atmosphere at an unprecedented spatial resolution of 3.5 km x 5.5 km (Figure 1). When statistical techniques are applied to the raw NO2 measurements from TROPOMI, we can boost their spatial resolution and discern differences in NO2 levels among individual neighborhoods. These satellite data can then be synthesized with sociodemographic data in census tracts of the United States to better understand “environmental justice” issues related to NO2. Census tracts are small geographic areas, which are approximately the size of a neighborhood, and contain generally 2,500 to 8,000 residents. Tracts’ boundaries follow visible features, such as roadways. Figure 2 illustrates the alarming colocation of NO2 and minoritized populations in California’s Central Valley, a region long-challenged by poor air quality.

Figure 1. A visualization of TROPOMI’s daily coverage of NO2 and other air pollutants and greenhouse gases. Credit: ESA/ATG, http://www.tropomi.eu/gallery/tropomi-daily-coverage.

The COVID-19 pandemic provided a natural experiment in which anthropogenic emissions–mainly from the passenger vehicle sector–plummeted in urban areas. We took advantage of this experiment to investigate how NO2 changes varied across racialized, marginalized, and minoritized populations versus majority populations in the United States and what these changes can teach us about future ways to combat environmental injustices and protect public health. This research, coauthored by Drs. Susan Anenberg and Daniel Goldberg, was published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Figure 2. (Left) Census tract-averaged 2019 tropospheric NO2 levels from TROPOMI and (right) 2019 estimates of race in census tracts. Industrial facilities are denoted with black dots, and highways and interstates are shown in black lines.

Major urban areas in the United States saw broad decreases in NO2 during spring 2020 (March – June), but changes were not even for different communities within urban areas. We found that the communities that experienced the largest decreases in NO2 had nearly three times the proportion of non-White residents than communities with the smallest decreases. What was more alarming, though, is that despite the decreases that preferentially occurred in Black and Brown communities, these populations still experienced higher levels of NO2 during the pandemic than majority White communities experienced prior to the pandemic (Figure 3). For example in the New York City metropolitan area, NO2 levels during the pandemic in the least White communities were roughly 20% higher than NO2 levels in the most White communities prior to any unprecedented emission decrease before the pandemic.

Figure 3. NO2 decreases during the pandemic were uneven for the most White (blue dots) and least White (orange dots) communities in major metropolitan areas of the United States. The solid lines denote pre-pandemic NO2 levels in 2019, and the dashed lines show NO2 levels during the height of pandemic-related lockdowns in March – June 2020.

We attributed these uneven changes and the persistent NO2 disparities to the inequitable siting of major roadways in racialized and minoritized communities and the presence of highly-polluting diesel trucking on these roadways. Complementary research also points to diesel traffic as a dominant source of environmental justice issues related to NO2. Our results indicate that simply removing passenger vehicles from roadways, as was unintentionally done during the COVID-19 pandemic or that could be accomplished in the future through electrification or a switch to active and public transport, will not be sufficient to reduce or eliminate NO2 disparities. Rather, policies that target heavy-duty diesel traffic should be a deliberate aspect of future efforts to advance environmental justice in the United States.

Beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, we have been working alongside stakeholders and a team of scientists from around the United States to better understand environmental justice issues through the lens of satellite data. This project, funded through NASA’s Health and Air Quality Applied Sciences Team, specifically aims to enhance the ability for stakeholders to map environmental injustices and identify communities disproportionately affected by health risks related to NO2 and a myriad of other environmental stressors. We welcome all interested in joining this growing community of environmental justice practitioners to attend our monthly team meetings.

Edited by Mengze Li, Athanasios Nenes, and Roy Arindam

About the author:

Gaige Kerr is a research scientist in the Department of Environmental and Occupational Health in the Milken Institute School of Public Health at George Washington University. He received his BSc with honors in Atmospheric Science from Cornell University and his MA and PhD in Earth and Planetary Sciences from Johns Hopkins University.

In his research Dr. Kerr uses big data from atmospheric models and satellites to understand the role of meteorology and emissions on ambient air quality and disparities in air pollution and associated disease burdens. He currently serves on several boards and committees for the American Meteorological Society and previously was an Air Quality Fellow for the U.S Department of State’s Greening Diplomacy Initiative.