Public engagement and outreach in science is a big deal right now. In cryospheric science the need to inform the public about our research is vital to enable more people to understand how climate change is affecting water resources and sea level rise globally. There is also no better way to enthuse people about science than to involve them in it. However, bringing the cryosphere to the public is a little more difficult when compared to other fields of science. Whilst volcanologists can cause mini explosions, seismologists can simulate earthquakes (such as Explosive Earth at last year’s Royal Society science fair) and realistic rivers can be simulated using interactive stream tables, combining ice and glacier dynamics in a public engagement setting can a little more challenging!

Despite the challenges involved in bringing the cryosphere to the public, a huge variety of great outreach projects concerned with glaciers exist, which deal with different aspects of the cryosphere; from using glacier goo to display how glaciers flow, recreating hydrology of a glacier with ice blocks, dressing up school children in fieldwork kit, or passing wires through ice to show regelation at work. But what should you keep in mind when planning your next cryospheric themed outreach activity?

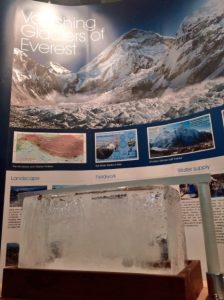

Figure 2: The Vanishing Glacier of Everest stand at the Manchester Science festival [Credit: Owen King].

Keep it simple. By nature, academics are good at complexity. However, the most effective project I have been involved in was very simple – one where an ice block simply sat and melted (see our Image of the week). The team involved with this project came up with a vast array of complex ideas when planning the stand, but settled on the simple, effective idea of an ice block – which has been a great hit. The stand has now been to numerous science festivals, and people are constantly surprised by the ice being real! Once past the initial shock we have a great base from which to start conversations on the basics of how ice melts to the impact of climate change on glaciers around the world.

Keep it broad. Academics are also very good at forgetting just how specific their area of research is. You may want to link your outreach work to a particular project, but if you try to attempt something very specific you will spend a great deal of time talking to public about the basics before you get to the detail. To ensure everyone can get something out of your outreach work the best way is to provide a platform on which the basics can be taught but, if a conversation takes you there, you have the resources to explain your research in greater detail. At ‘Vanishing Glaciers of Everest’ we have the ice block for introductory discussions, but if someone gets really interested in the details we have figures and photos on the stand behind that can be used to introduce more complex areas of our research (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Glacier goo at science and engineering week, Aberystwyth University [Credit: Morgan Gibson]

Make it interactive. Generally, people don’t want to be talked at. Instead, most people want to discuss what they know with you, so make it easy for them to do so. Give people something to do (e.g. glacier goo – Fig. 3) as soon as they reach the stand that they can explore on their own. You can then join them and ask exploratory questions, which starts a discussion rather than presenting to them. You are then likely to engage the person you are talking to much more effectively, and may well find out something yourself!

Consider all ages. Outreach work is often focused on children. However, adults are also a key demographic on which to focus. Engaging teachers and parents is vital to really bring home the importance of science to children in school and at home; I have found that almost all children have an interest in what you are saying, but without enthusiasm and interest from the supervising adult your hard work at engaging the children will not be encouraged once they leave. Consider how you will show how your aspect of science is fun, but also relevant to peoples’ everyday lives – that way you can appeal to both demographics.

Be innovative. Hanging an ice block from a wire to show regelation is cool, as is glacier goo. However, increasingly I am finding people have seen these experiments before, and are finding it all a little boring as a result. By repeating the same experiments again and again we are in danger of suggesting our research is static, which is obviously not the case! So be inventive when you are coming up with ideas and don’t forget all the new technology you could include!

Figure 4: “Icy bear” – a Twitter-based public engagement ‘project’ that documents research on microbes on ice, and fieldwork, across the world [Credit: Arwyn Edwards]

Be prepared for anything. I’ve had people talk to me, at length, about how the best way for us adapt to sea level rise is for all of us live in high rise blocks on hill tops. I’ve also spent a great deal of time explaining how we know anthropogenic climate change is real. You will get some strange questions and bold statements, but they are part of the experience. Keep an open mind and be positive; you meet amazing, interesting people at these events, and I have had conversations that have led to new research ideas, or to me rewriting paragraphs of a paper due to discussions at such events.

Be reflective. Spend some time considering the effectiveness of your outreach once you have finished (and recovered) from an event. What worked well and what didn’t? Do aspects of your stand or event need adapting for different audiences? Can you expand what you are doing to enable more flexibility on the overall message for your work? Being reflective will only lead to more effective public engagement, more interesting discussions, and you feeling satisfied that you have enthused and engaged public on your research, so it is worth doing!

Public engagement, done right, is incredibly rewarding. You not only spread your enthusiasm for research and get to discuss your work with a huge range of people, but it also enables you to show people that like science is relevant to everyone.

If you want to see some public outreach in action for yourself, the upcoming International APECS Polar Week (September 18-24, 2017) is a great chance to get involved in some outreach activities. For example, the #PolarWorld Frostbytes competition, to design a short audio or video recording used as a tool to help researchers easily share their latest findings with a broad audience!

Edited by Emma Smith

Morgan Gibson is a PhD student at Aberystwyth University, UK, and is researching the role of supraglacial debris in ablation of Himalaya-Karakoram debris-covered glaciers. Morgan’s work focuses on: the extent to which supraglacial debris properties vary spatially; how glacier dynamics control supraglacial debris distribution; and the importance of spatial and temporal variations in debris properties on ablation of Himalaya-Karakoram debris-covered glaciers. Morgan tweets at @morgan_gibson, contact email address: mog2@aber.ac.uk.

Morgan Gibson is a PhD student at Aberystwyth University, UK, and is researching the role of supraglacial debris in ablation of Himalaya-Karakoram debris-covered glaciers. Morgan’s work focuses on: the extent to which supraglacial debris properties vary spatially; how glacier dynamics control supraglacial debris distribution; and the importance of spatial and temporal variations in debris properties on ablation of Himalaya-Karakoram debris-covered glaciers. Morgan tweets at @morgan_gibson, contact email address: mog2@aber.ac.uk.